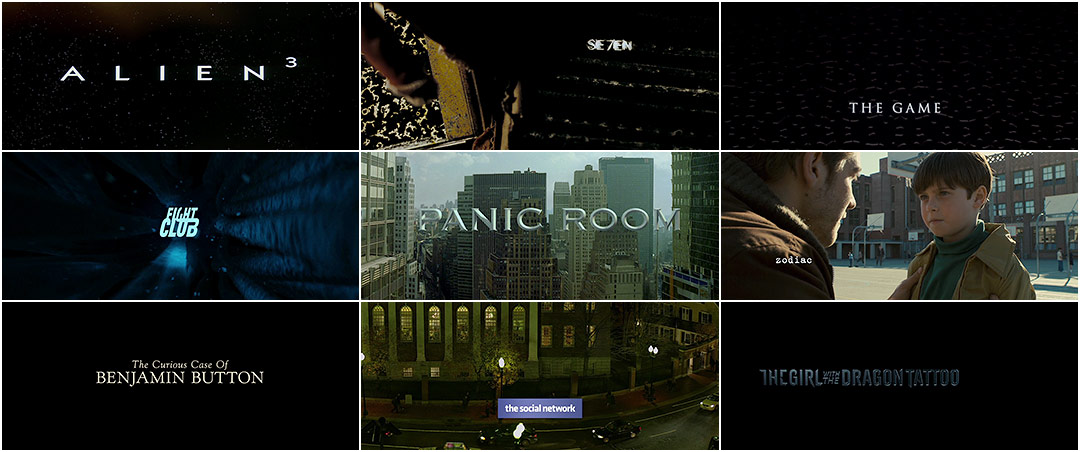

Perhaps no other living director has done as much for the art of the title sequence as David Fincher. The filmmaker’s work inarguably helped kickstart the title design renaissance of the 1990s, a revival that the medium still enjoys to this day.

From the slumberous doom of Alien³ and the meticulous grotesquery of Se7en to the dreadful reminiscence of The Game, the electrical inner workings of Fight Club, and the majestic imposition of Panic Room, the director’s title sequences are as distinct from one another as they are distinctly the works of Fincher.

Throughout the many disparate worlds and settings of his films, Fincher’s audiovisual prosody remains unmistakable. There’s always a familiar rhythm at work, a recognizable but elusive metre in the mix. Sometimes it’s lurking just below the surface, other times it’s an inescapable barrage, hammering into your skull. A viewer might glimpse it amongst the grim ephemera of John Doe’s lair, read it in the semi-cryptic lettering of Zodiac’s title cards, or hear it in Karen O’s discordant howl, but it’s always there, teeing up the audience for what is to come.

An extended discussion with Director DAVID FINCHER, expanding beyond our first interview for The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.

Your films are known to feature interesting title sequences – would you say that you're a fan of titles in general?

Absolutely! Obviously, all the Saul Bass stuff is really inspiring to me. I wasn’t so much aware of the people that worked on North by Northwest or their importance as much as I was like, “That’s a really interesting way to present something.” I looked at it as part of the entertainment form.

Director David Fincher on location for The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo

You know, Butch Cassidy & the Sundance Kid has an amazing title sequence that was originally a sequence in the movie. It featured Katharine Ross, Redford, and Newman in Bolivia, where they see a film about their own exploits. It’s a beautiful idea for a scene and it also made for an amazing title sequence because it set up the idea of the Western as something we’ve come to know through the movies. The film was such a revolution in terms of thinking about the Western and in terms of buddy movies! I look at that movie and its title sequence and I think, “That was a scene in the film – that was written in the script – but it was used in a completely different way.” They decided maybe it was too dour or negative, that maybe the ending would be more provocative without teeing up the events.

So it’s less about the sequence and more about your experience with the film overall?

Yeah, I can’t think of many great title sequences to movies that I dislike, so it’s as much about it being a good title sequence as it is about it being a movie that I enjoyed. That’s when they stand out.

And that’s informed your own approach to titles, obviously.

Definitely. It's an opportunity. The sequence for Se7en did very important non-narrative things; in the original script there was a title sequence that had Morgan Freeman buying a house out in the middle of nowhere and then travelling back on a train. He was making his way back to the unnamed city from the unnamed suburban sprawl, and that's where the title was supposed to be – “insert title sequence here” – but we didn't have the money to do that. We also lacked the feeling of John Doe, the villain, who just appeared 90 minutes into the movie. It was oddly problematic, you just needed a sense of what these guys were up against.

Se7en (1995) — opening title sequence

Kyle Cooper, the designer of the title sequence, came to me and said, “You know, you have these amazing books that you spent tens of thousands of dollars to make for the John Doe interior props. I'd like to see them featured.” And I said, “Well, that would be neat, but that's kind of a 2D glimpse. Figure out a way for it to involve John Doe, to show that somewhere across town somebody is working on some really evil shit. I don't want it to be just flipping through pages, as beautiful as they are.” So Kyle came up with a great storyboard, and then we got Angus Wall and Harris Savides – Harris to shoot it and Angus to cut it – and the rest, as they say, is internet history.

I don’t believe in decorative titles – neato for the sake of being neato. I want to make sure you're going to get some bang for your buck. Titles should be engaging in a character way, it has to help set the scene, and you can do that elaborately or you can do it minimally.

The Game (1997) - opening title sequence

For The Game that was pretty simple: the idea of these weird home movies. We didn't end up running titles on them – we saved them until the end – but we had the Polygram thing at the beginning with the puzzle pieces. It was just an elegant introduction to who the character is. Social Network went even further – it was simple as dirt.

A progressive jpeg.

Yeah, exactly.

The Social Network (2010) - opening title sequence

And Zodiac?

That was much more in the vein of Social Network. We had a job to do: we had to send this guy off to work, he's got to drop his kid off, we've got to set up San Francisco in 1969, so its function is primarily narrative and then the titles just need to be included.

Zodiac (2007) - opening title sequence

You seem to use the idea of a prologue a lot: Se7en is a prologue, The Game is a prologue.

Yeah, hopefully it's a little more abstract than that though. In Se7en, you see a guy shaving and cutting the tips of his fingers off... You don't know who the fuck he is. You're just thinking, “What is this weirdness? How does this get folded into the soufflé that will be this movie?”

For instance, Panic Room was just graphic fun. I was playing around. For years we'd joke: “When you see the credits for a movie, what is that type? Is it supposed to be a projection over the scene or is it supposed to be there? Let's ask that question.” So we started playing around with that idea.

In the scripts that you've worked with, how often are the titles detailed? Is it purely, "Insert Sequence Here"?

Almost never. For Panic Room, the sequence takes a trip up the island of Manhattan through quick shots of buildings to get the idea of, “You're downtown, you're midtown, you're traversing the park, you're moving to the west side: here's where the story takes place.” This was the same idea as the title sequence to West Side Story, so we had to do something a little different.

Panic Room (2002) - opening title sequence

With Fight Club, the whole thing could have started with the sound of a gun being cocked, opening on Edward Norton – which is how it began in all the preview screenings – but I had this idea to begin with the electrical impulse of information between two synapses to cue the fear or panic receptors in Edward Norton’s character's brain. Then we literally pull back, changing in scale all the way back, and we pull out through his forehead.

Now, did we need that? No, we didn't. We probably spent $750,000 or $800,000 dollars on the title sequence. So to go to the studio and say, “Hey, this could be a really good idea. We've already seen the movie with the sound of a gun cocking and it works pretty good. But this... this will put asses in seats!” – it's a gamble. They don't see it that way. So it's a minor indulgence, but I remember that stuff.

Fight Club (1999) - opening title sequence

You're not shy about exploring the potential of the title sequence.

Yeah, it's fun. Why wouldn't it be?

Actually it's funny, when I finally saw Enter the Void... one of the things we tried to do on Fight Club was to literally flash the credits. I wanted to burn them, sear them into people's eyes, and have them on screen for like four frames and then let them decay away. Needless to say, when we ran that past the guild it didn't go over well, and I was so mad when I finally saw Enter the Void! I was like, “That's the thing to do!” Here it is: it's a jackhammer to the middle of your forehead – your third eye.

And Alien³?

[laughs] I don't want to talk about that. Alien³... that was always designed to do away with the cast from the second film as efficiently as possible.

Alien³ (1992) - opening title sequence

I was talking with a friend last night about that and they hated the fact that you killed the characters, whereas I actually liked that and thought it was very interesting.

Yeah, I thought it was kind of bold.

Right, it's something that doesn’t happen very often.

The writers weren't bringing them back. They had a script that didn't include them, so we had to tell the story of their disappearance.

David Fincher on the set of Alien³

So that wasn't in the script that you were working from?

The script had the Sulaco pod being ejected, but we decided afterwards that we needed to see what happened on the ship that led to that event.

I was also curious about the Fox fanfare which ends on the minor note before it goes into the film. It also goes from mono to stereo (or surround), which is interesting. Was that you or the sound designer?

That was me. Well, it was me and Elliot Goldenthal. "Can you take the Fox fanfare and just sour it?"... because we're about to do that with the film.

And Benjamin Button has the button-based studio logos, but it actually doesn't have any opening titles.

Nope. We had a bunch of companies pitch for the title sequence and almost everything that we looked at had this sort of antique, sepia, old china cup kind of feeling. Pretty much everything we saw had that doily essence... like a grandma's idea of a title sequence.

So you decided to go without?

Yeah, we shit-canned that! Then we just wanted to figure out a way to commingle the Warner Bros. and Paramount logos in a way that was a little unexpected.

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (2008) - opening studio logos and end titles

So as you get older, what has changed for you in terms of your filmmaking?

That's sort of like going through pictures of yourself from high school. You think, “Wow, I looked like that?” I don't think you're aware of the changes until you look back on the last three movies or something. I don't really have a plan. I think I’m always interested in something new. The stuff that interests you now probably didn't interest you when you were 20.

If I were 15 now, I'd be such a glutton for the images we can make now, the kind of flawlessness that you can achieve. When you look at Close Encounters... it's just astounding the kind of mastery those guys had. That was so hard to do! Now we can send out for effects like pizza, but with Greg Jein and those guys, they were literally forging images.

Or with The Empire Strikes Back, they took an entire soundstage and filled it with baking soda, and then somebody popped up out of little holes and moved a huge model a couple of millimeters at a time. Now that can be done perfectly, in a way that no one will ever be able to see. It's astounding.

On the set of The Empire Strikes Back, Doug Beswick, left, animates the snow walker, with stop motion animator Jon Berg (center) and Phil Tippett (right).

From the book Industrial Light & Magic: The Art of Special Effects.

It's interesting that you have such a love for that kind of analog mastery, but if you look at your films they're often very CG-driven – you're known for pushing that technology.

I tend not to think in terms of tools or what I want to rent that day. There will be times when you’re defining your methods and you go, “OK, I need a crane on this day for this, but I’m not going to carry a crane with me for 100 days of shooting and incur those costs just because I might be curious about a shot. When you’re looking down on a scene or a character, that has to come at a very specific moment. It’s not the kind of thing that you experiment with.

You know, CG is such a blanket term. The fact is: you just can’t find somebody to do rear-projected or color separation matte paintings because everyone’s gone digital. With CGI, often the technology has a patina that rubs off on the project. In Zodiac, I used three-dimensional or two-and-a-half dimensional matte paintings not because we specifically had that in mind, but because it worked stylistically.

Right now, we’re working on a title graphic that has neon in it. Well, you can do neon with CG easier than with glass because you have the freedom to look at it from different angles. It would be nice to make the sign in real neon, but it’s not very practical.

I can’t hit someone with a bus, but how do I make you think you saw a guy get hit by a bus? That’s just practical problem solving.

I think all filmmaking is sleight of hand – the most basic form of low magic. So having an idea of different techniques that can help you get your vision across is only practical in this day and age. I don’t have a WETA. I’m not looking to keep people busy or keep the doors open on a visual effects facility, but if I’m shooting a movie that takes place underwater, I have to ask if it’s more practical to shoot underwater or to do it as motion capture and CG. I can’t hit someone with a bus, but how do I make you think you saw a guy get hit by a bus? That’s just practical problem solving.

Do you enjoy that process or do you ever find it frustrating given that the possibilities can be so limitless?

I definitely enjoy the “dreaming up” of the whole thing. That’s where it’s at its most fun. But I often say that I think the beginning of any creative journey is the defining of not only the visual impact and product, but also the ways that you’re going to limit the execution. I very rarely use Steadicam because it’s a frustrating process for me. It’s a style of filmmaking and a style of camera operation, and when those operators are at their best it can be an amazing thing, but it’s very present, it’s very subjective. That kind of floating subjectivity is a very odd thing for me.

Yeah, I was curious about your use of handheld camera...

[laughs] Or non-use?

Yeah. In The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, like a lot of your films, there seem to be very few handheld shots.

Yeah, the sequence in the subway station was all handheld, and then we used it at the end when Lisbeth runs after Martin. Basically I don't like it. I like a very specific kind of operating. For instance, I don't shoot a lot of shots that require you to follow someone's face or eyes. I like to find a frame that the actor can sort of play in. Handheld has a powerful psychological stranglehold. It means something specific and I don't want to cloud what's going on with too much meaning.

One of the things that was interesting to me about Panic Room was the idea of the disembodied camera movement that sets up the night when they move in. It's important to me that the camera can go under a door or through a keyhole because that sort of says that there aren't 80 people here. There isn't a whole crew. It's effortless to go between floors, to go through a wall to find out what's happening inside a room. On a psychological level it shows the audience that we're unencumbered and we may show you some shit you don't want to see. It helps with the tension. When there's a lot of reframing and a lot of an actor moving their head and the camera panning immediately with them, if feels to me like there's a crew in the room – it takes me out of it, it makes me feel safe.

Panic Room (2002) - uninhibited camera scene

It's like the psychology of music. The runaway cab scene in The Game has no music in it. We were sitting there putting temp music under that scene and it felt cheesy. That's not to say that there haven't been incredibly terrifying moments in movies that have been underscored – Psycho is a perfect example – but you want to pick your moments. Likewise in Dragon Tattoo when Blomqvist goes up to the glass house, peeks in, and finally opens the door and lets himself in, there's no music. If there was, you’d know you were in a movie, and you'd feel safe. I like playing with that. There's a certain expectation of that *bum bum bummm* scary moment, but when you withhold that, it creates a different kind of anxiety. Audiences are very sophisticated about how they're being manipulated. And then later on you take a moment and put some Enya on!

Haha, right. And in Se7en there's the foot chase scene which is obviously the opposite of that, using handheld...

Well, normally in movies characters just run pell-mell after the antagonist. I always thought, “God, if someone was shooting at me, I would be terrified to turn any corner!” If you set it up properly and put the audience in that subjective place, handheld is the perfect way to get that feeling. Otherwise, it gets very overused.

Se7en (1995) - foot chase scene

Especially in stuff like HBO’s The Newsroom where everything is handheld, it can be overwhelming.

Right. That idea of presenting verisimilitude can be taken back to Costa Gavras and Z, but I’ll take it to Leslie Dektor in the early ’80s when he started what we now call “shaky cam.” Leslie does not wing it – he has an amazing sense of light and composition. The ads that he did in South Africa are some of the most beautiful things ever photographed. And then in the early ’80s with those Maxwell House commercials he threw it all away and said, “Yeah, it can be beautiful, but I’m also going to make it look like the camera was just running. Here’s the product shot, here’s the cup of coffee, and here’s the can, and we’ll just scan past it.”

If it’s applicable to a story I could see using handheld – I could see it being part of the shorthand of the medium, but mostly I think it’s quicksand.

The identification that I had with it – that I think a lot of people did – was of a subliminal message that can be traced back to the Zapruder film. That film is probably the home movie of our collective unconscious as Americans and it’s the only record of the most brutal and sad and life-altering document that exists of that moment. There’s no other piece of cinema with that kind of power. The fact that it was so haphazardly photographed, and that there are skipped frames in the Super 8, gives it a kind of power that was wisely and very adroitly and beautifully co-opted by these commercial makers at the time and later abused into oblivion, to the point of cliché. There are times when it’s done well, of course. I thought United 93 and a lot of the Bourne stuff was superbly done, but there’s a lot of times where it’s just a gimmick. If it’s applicable to a story I could see using handheld – I could see it being part of the shorthand of the medium, but mostly I think it’s quicksand.

There were guys like Peter Smillie who could mix very rigorous and beautiful tableaux with little bits of handheld in perfume commercials or something. It’s a very odd thing – when you see how Kubrick uses Steadicam in The Shining, you’re not aware of the change in elevation, of the rounding of the corners or the drops of shoulder. That’s the reason those shots took 90 takes to do with a Steadicam; to make it look like it was on a dolly, like it’s maintaining the rigidity of that horizon. That’s what makes it stunning to this day.

Then, you have the opposite effect of that which is Carpenter’s Halloween: the float up the stairs, the fact that this is a child – a disembodied POV with this mask, and the culpability that you have as a peeping tom – that was an interesting moment in cinema. A really great, practical, and powerful artistic commingling of text and presentation. But as anything that is exciting to people, it will often be co-opted by others who aren’t as disciplined about it and all of a sudden it becomes cliché.

Steadicam examples in The Shining and Halloween.

So what's influenced you in your career? It seems like you had a very clear path of what you wanted to do from the start. What sparked that?

I was eight years old and I saw a documentary on the making of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. It had never occurred to me that movies didn't take place in real time. I knew that they were fake, I knew that the people were acting, but it had never occurred to me that it could take, good God, four months to make a movie! It showed the entire company with all these rental horses and moving trailers to shoot a scene on top of a train. They would hire somebody who looked like Robert Redford to jump onto the train. It never occurred to me that there were hours between each of these shots. The actual circus of it was invisible, as it should be, but in seeing that I became obsessed with the idea of “How?” It was the ultimate magic trick. The notion that 24 still photographs are shown in such quick succession that movement is imparted from it – wow! And I thought that there would never be anything that would be as interesting as that to do with the rest of my life.

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2011) - opening titles

On the Dragon Tattoo Blu-ray, there are some amazing extras. There’s one in the editing room with you, Angus, and Kirk and you’re watching the footage. You’re shooting on RED* at 5k, but then you take that and readjust shots as you watch a cut. The technology seems like it’s making it easier to change things after the fact...

*RED - The Red Digital Cinema Camera Company manufactures digital cinematography cameras and accessories.

Yeah, you can refine things. A movie is written and edited multiple times. It’s in black and white and everyone has the pages – and that’s what it’s supposed to be – but then you’re on set and it’s raining or it’s not. It’s hot or it’s not. It’s day or it’s night... then there’s that moment where people come in and repeatedly experience something in real-time right in front of you. When you’re shooting, you’re completely out of chronological order, so you’re giving it your best idea of that moment. You get a take and for whatever reason, it really works for you. Sometimes you can articulate it and sometimes you can’t.

Then you can refine those things and in the editorial process it gets rewritten because the story is broken down chronologically. Maybe you decide later on that an actor has drawn a conclusion too quickly, they’ve invested too early, missed a line, and maybe in that moment the camera was being repositioned because the missed line made everybody anxious, and so you go in and make it part of the intention. Those are two separate things: there’s the intention, and then there’s what you’re gifted with while shooting, because it has its own life which is constantly being rewritten. You can go out and shoot and get the select takes that you want, but sometimes blunt force trauma is not going to make it go together.

The mere act of decision-making inflicts your worldview on the proceedings, and you can't hide that. You put your fingerprint on your film.

Let's talk about the design of your films. It seems like you have an aesthetic signature even though no two films look or feel the same. How do you approach the design? Do you see them almost as 'branding' projects?

When you look at film literature – not only criticism but when people write about movies – for the most part, people are drawing inferences and connecting dots in a very personal way. For somebody to be so interested in a movie that they want to write about it is a rare thing, but when it does spark something in them and they put pen to paper to say why it moved them and to talk about the connections they saw – those connections aren’t always intended.

A lot of what people don't want to talk about is that when a movie works in a giant way, for millions of people, and it becomes a phenomenon, you're seeing something that's connecting in a way that is irresistible. And a lot of people don't want to think about movies in those terms because it conjures all these ideas of mind control like in The Manchurian Candidate or subliminal messages or...

The Parallax View?

Yeah, exactly. I've never seen anyone master the form enough to be able to do that, but let's get beyond that: as a filmmaker, you're the ringmaster. You don't have control over every performance, every hair being in place, wardrobe, the importance or potential importance of your actors, but you have a discipline and a craft that you bring to the problem solving of telling a story. The pictures are a quarter of that package – what people are wearing, where they're standing, how they're lit, what their makeup is like – and all that stuff's important. Then there's the sound, and that's another quarter of it and that includes the music, the density of the surrounding world. There's the amalgam of those two, and that's only half of the movie experience.

And THEN there's the audience, and what they bring to it. You're trying to do your magic trick, you're laying down all your cards, but there's something that the audience brings to it: their gullibility, their willingness to participate. If you're telling a story in a very similar way that a lot of stories are told, that can be one of two things: it can be very comfortable in its familiarity or it can be very dull in its familiarity. You're gambling on something two years before an audience is going to see it and it's such an important part of cinema.

So, anyway, like it or not, I have a behavioural barometer that is either a curse or a gift. The idea of an aesthetic signature is kind of inevitable because everything that you present to an audience is going to be colored or tempered by your personal likes and dislikes. It's not about remaking the world the way that I'd like to see it; rather, I look at it based on a character's purpose in the story. The mere act of decision-making inflicts your worldview on the proceedings, and you can't hide that. You put your fingerprint on your film.

There’s a lot of grab-ass and douchebaggery that goes on and it’s not all serious and no one has all the answers.

Do you think you are more involved or you make more decisions than other directors?

Well, I don't go on other people's sets, you know? I've worked for George Lucas, I've worked for Ron Howard, Steven Spielberg, Wolfgang Petersen... I saw how they delegated but I didn’t work intimately with them. I never worked with them the way I do now with a production designer or a cinematographer; I worked for them as a lackey and a visual effects nerd.

It was fascinating to watch those behind-the-scenes documentaries for Dragon Tattoo. As a viewer you get the idea that it’s pretty accurate in showing the sheer amount of work involved. It's very fly-on-the-wall.

*EPK - A press kit, often referred to as a media kit in business environments, is a pre-packaged set of promotional materials of a person, company, or organization distributed to members of the media for promotional use.

Right, and that's why we shoot behind-the-scenes stuff for 60 or 70 days. We don't want it to be like an EPK*, we want the cast and crew to be comfortable, to get used to David Prior standing around with a video camera. There's a lot of grab-ass and douchebaggery that goes on and it's not all serious and no one has all the answers.

There’s a quote that I found –

Uh oh!

It says: "My idea of professionalism is probably a lot of people's idea of obsessive." Is your professionalism ever tiring or exhausting?

[laughs] Well, I’m sure it must be for other people.

I mean for you. Given the amount of work you personally do on a film – the number of decisions you make on a daily basis – do you ever feel exhausted by your "professionalism"?

I honestly don't know how to do it any other way. Before you make a movie for a studio, you have to sign a contract that says you're going to do it for plus or minus a certain amount. Your final cut gets taken away if the film’s budget is plus or minus five percent of that, so you have to take that seriously.

Part of it is articulation – letting everybody know exactly what each scene is about – like, this scene [in Notorious] has to show that it's a cocktail crowd at a big gathering, but it's really about Cary Grant and Ingrid Bergman and their conversation about the key in her hand.

Notorious (1946) - key exchange scene

So there’s a wide shot to show how swank everything is but then you move to an over-the-shoulder shot and it's all about how much they're conveying while barely moving their lips. Then for the insert shot, man, that key better be memorable! When she passes it to him, you’ve got to decide: Is it chrome or nickel or iron? Should it glint? Answering those questions is just being responsible as a director.

You know, I remember going to see The Crying Game and sitting in the theatre, thinking, "This is a beautiful story about Forest Whitaker and this cross-dresser. And it's kind of amazing and I have so much respect for the way it's being told because there's absolutely no comment being made about the cross-dressing..." And then everyone around me is going, "It's a guy!" And I was like, "Are you fucking kidding me? Seriously?" For me, it was just as interesting and compelling and beautiful that the reveal was going to happen for Forest rather than for the audience. But you know, people see different movies! We were just watching two completely different movies.

House of Cards teaser poster

What are you working on now?

Well, trying to figure out a sequel to Dragon Tattoo. We've got to be able to make it our own thing. And I'm trying to get House of Cards rolling – that's what Neil Kellerhouse and I are working on now.

Is this your first foray into TV? What led you to that series?

Yeah. I just really liked the story. I liked the characters. It's an interesting look at politics.

At what stage is that?

Well I shot the first two episodes, and we're sound mixing in the next couple of weeks and then finishing. James Foley has directed two and Joel Schumacher directed two, and now Charles McDougall has directed two. It’s up and running so that's a fulltime job.

Do you want to do more TV?

I like television. There's something amazing about having to put on a show. You have an idea for a scene, you talk it out, it gets hammered out in rough form, you do a rehearsal, you look at it and figure out what's working, you go away for an hour, and then – bang! – you're shooting. There's no navel-gazing at all. Anytime you're sitting there scratching your chin, you're taking time away from shooting. It's a very different discipline. It's exciting.