We are but beneficiaries of both the depth of design and the intellectual complexities of Richard Morrison's body of cinematic title sequences. Indeed, what better than researching a man whose work is a foregone conclusion in heart and wonderment?

The son of a film editor, Morrison became a master at internalizing a director's intent and distilling it for the title sequence. From Morrison, “I look for a nuance – a subliminal energy in a film – that I can then work into an idea."

Morrison discusses six of his sequences...

Brazil

The optical effects in Brazil have quite a timeless quality to them. I did not consciously set out to create something so lasting. It was more of a serendipitous happening.

Terry Gilliam is a very hands-on director, throwing ideas at you and getting really involved. So, in this case, creating the sequence was something of a process. I never quite knew what to expect, until seeing the final effect and thinking, ‘Yeah, that’s it!’ That’s usually how it all looks when you work with very visually striking directors. They will already have their own ideas and just try to work with me to create them. And so if you work for someone who is visually more inspiring, they tend to give you more rope… It is good experience though, because it fuels your creativity and in a weird kind of way turns it into something that is ageless, simple, and unique, as with Brazil…

Batman

The Batman 1989 environment was not that homogenized. In fact, there weren’t many people on the same platform and we were all very individual.

I did not know Tim before so I had to pitch for the project. We just had to make sure what we were about. I sat with him for a few minutes, and then just walked around the set of Gotham city. And that was it, really. I clearly remember I sat back in the car and all of a sudden, I knew it. I knew it had to be something about the classic Batman comic logo. I thought, ‘What if we think of that in a 360º move? How about if it’s in landscape? How about I make it something you can move around, so you don’t quite know what it is?’ So that was the idea and then I just invented the world around it. Nobody did anything like it before so that’s why it probably retained its timeless feel.

The Dreamers

As a creative, I find the idea is always the key and the means to do it is a secondary matter. Because of the nature of The Dreamers – its plot and timing – I wanted this sequence to look organic, just like in the old days. So I just started piecing visually abstract elements together, like in a puzzle, and decided to completely abandon any complex animation effects. It just did not fit in with the essence of the movie.

To preserve that ‘old school’ feel I worked as if everything was completely optical. You see, in the past you just could not see things in real time. And this had a tremendous impact on your pace of work, accuracy, thought process, and the whole approach really. You had to be a better planner. You had to be a master of accuracy. Everything you were doing was in real scale – very physical. You could not just press ‘delete’ and start over. By creating this sequence in this way I really had a genuine belief that this would actually work. Luckily, it did.

And so the main idea I applied was to use the Eiffel Tower as the background – for the interaction of the tower’s 3D shapes with graphically explored elements such as the typeface and colours. This, combined with the application of a continuous vertical camera pan, produced something of a lasting and very specific effect. I think most people now recognize The Dreamers just by that quite memorable title sequence.

High Fidelity

When working on this sequence I kept three notions in mind: make it original, simple, and distinctive enough. I believed simple content would be the answer to a finely tuned piece of work. Hence, the sequence abounds in this somewhat old-fashioned vintage style ‘brand identity’ approach with a titled logotype centrally set in a 3D background movement.

I knew the film would be humorously philosophical. So I thought it was perfectly natural to create some kind of a retro feel to reflect some of the older classic films, but also keep it feeling fresh and contemporary at the same time. Understanding where the film sat in its surroundings was absolutely vital. Although it is a short piece, the level of difficulty was naturally quite high – timing being one of the main reasons. Many creatives will tell you that short pieces are the most difficult ones because you need to ensure that you make the most of every single second, graphically and visually.

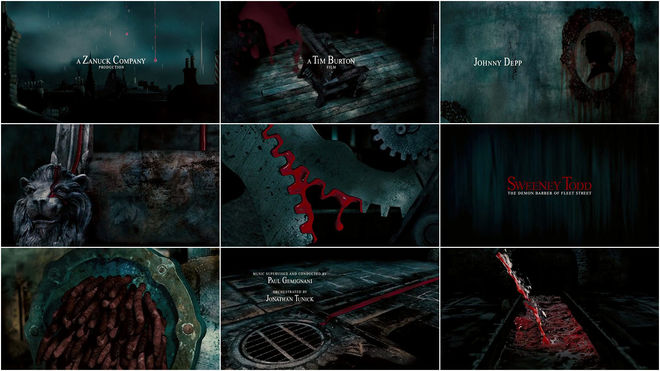

Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street

This industry is very specific and if you do a good job then you tend to be remembered by directors and producers. What I enjoyed most was coming up with the whole idea. I did not have to pitch to Tim but I turned this project into an internal pitch at th1ng. And so, a few days later, I had a room full of some truly outstanding creative work. I took it all to Tim and he just spread the pieces all over the floor and spent around a day or two looking through them. And then he just said: I really like this narrative piece (mine) and those coloured frames (Shay Hamias, director).

Animating blood and its movement became the most crucial and challenging element of the sequence. We had to build special platforms within which we imitated blood movement and filmed it. And we had to give it this comical feel, which worked really well. That was a dream project. We would love to work on something similar.

Vantage Point

It is an elegant piece. I liked the idea of random elements coming together before our very eyes, and I thought it would be very clever to use the red laser dot as a motif. It immediately introduced the theme of assassination and threat. Also, I think that the dark gold palette of these images strikes a chord with the filters used later to film Salamanca – there was this smooth transition between the titles and the first scenes shot from the helicopter.

The sequence had to be based around the idea of perspectives. So I graphically tried to create a web of intrigue to give viewers an accurate insight into what they can expect in the movie.