Sally Cruikshank has never been one to neglect the possibilities of the imagination. This is why she is responsible for some of the most vibrant and extraordinary worlds ever put to film. As an animator, filmmaker, and early Internet developer, Cruikshank takes illustration and spins it into world-building, creating lush, dynamic environments where the laws of our physical universe are bent, broken, and made new, where anything and everything can open its eyes, grow a mouth, and talk back.

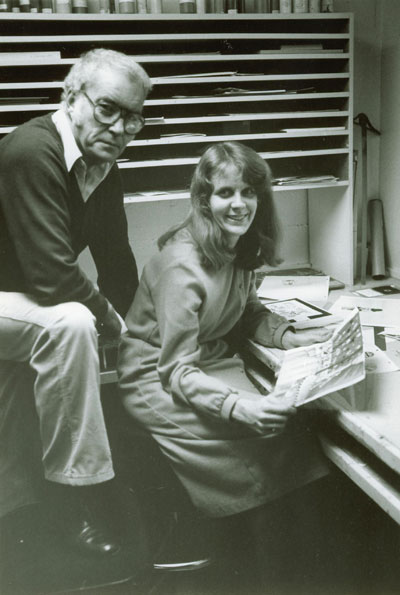

Sally Cruikshank at Snazelle Films, 1978

Taking inspiration from cartooning greats like Crumb, Fleischer, and McCay, and combining it with her own warped sense of humour, Cruikshank lets loose a gaggle of characters including talking ducks, anthropomorphized vehicles and furniture, and motley creatures from beyond, always walking that serpentine line between the world in front of us and the one in our periphery.

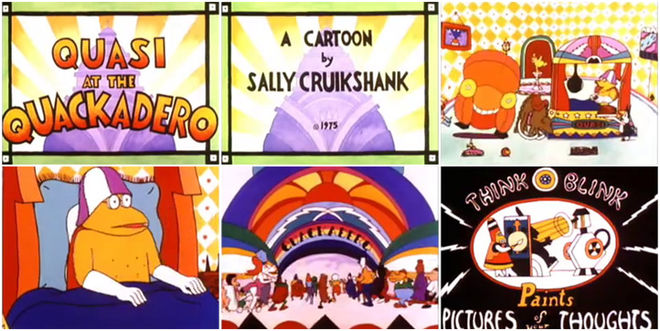

After whetting her appetite for animation in Massachusetts in the late ’60s, Cruikshank moved to San Francisco to pursue it more deeply, finding a willing patron in studio owner Gregg Snazelle. In 1975 she wrote, animated, and directed Quasi at the Quackadero, her most well-known and lauded masterwork of a film. It became one of the first countercultural films to find popularity on the midnight movie circuit and to break through to a mainstream audience.

In the ensuing years, Cruikshank strode ever forward, making more independent short films, contributing opening titles and animated sequences to major motion pictures, working with cherished children’s show Sesame Street, and diving into the strange abyss of the early Internet. Her work has been inducted into the National Film Registry and screened at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

While Sally Cruikshank is not yet a household name, she is responsible for some of the most innovative animated works in American history. In embracing psychedelia, the infinite, and the possibilities of line, shape, and sound, she lays bare the bones of the medium. Her work shines in the obvious joy it takes in itself, in the sheer exuberance of animating. Cruikshank’s liberties become our own, and we share the delight of creating a brilliantly bonkers inhabited world and letting anything happen. And she lets it all happen, all right.

In part one of our two-part feature interview with Sally Cruikshank, we discuss Sally's first animated shorts, her commercial work at Snazelle, and her first forays into animating sequences for feature films.

Part One

So, maybe before we get into the major film work and the commercials and Sesame Street and the National Film Registry, we can start at the basics. How did you get into animation?

SC: Well, I was an art major in school at Smith. In my senior year, I taught myself about animation and made a film. A professor helped me set up a photo enlarger and that got me started. I graduated early from Smith and went on to the San Francisco Art Institute because I wanted to get as far away from New England as possible! I made a couple of art films there, just on my own. One was called Fun On Mars, which was sort of my reaction to San Francisco.

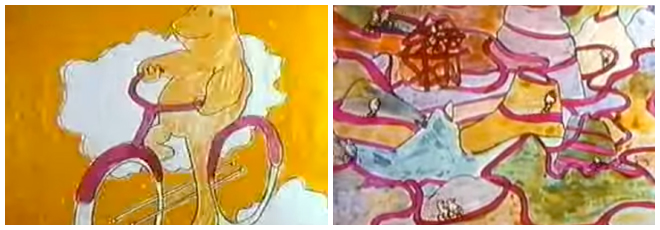

Stills from Fun On Mars, the short film Sally Cruikshank animated while at San Francisco Art Institute in 1971. Watch Fun On Mars on YouTube

That was followed by one called Chow Fun, for which I got a tiny grant from an organization that eventually became South by Southwest, many years later. While I was editing Chow Fun at Snazelle Films – I went in and rented a Moviola to edit it – I got a call that the boss wanted to see me. I finished the editing, and I thought, “Oh man, I must’ve broken the Moviola.” I thought I was in trouble. Instead he said, “I want to hire you to experiment in animation.”

E. E. "Gregg" Snazelle and Sally Cruikshank at Snazelle Films, one of the first large film production companies in San Francisco

And that’s how you got hired at Snazelle?

Yeah, so Gregg Snazelle hired me and I had this great job where they let me work on my own films. Gregg called it “heading the animation department” but it was just me, so I was just heading myself! He was hiring me to do commercials when we got them, and then the rest of the time to experiment with animation.

Watch the Levi's commercial "The Stranger" produced by Snazelle Films.

They had recently done some great and recognized commercials for Levi’s using rotoscope, one was called The Stranger and it was very well designed, by Chris Blum. Gregg Snazelle won many awards for them. It was done in rotoscope which hadn’t been seen much since the ’40s. They revived rotoscope, really.

So then I did some commercials for them. I believe I did the first commercials for The Gap when it was still just a clothing store in San Francisco, and I did a commercial for Connie Shoes.

I’ve been looking for the rest of those commercials. I used to have them on a 3-quarter inch tape, but that wasn’t a very strong format. They’ve all disintegrated. Formats become obsolete so fast, it’s just stunning. One-inch tape, too. That used to be like the rock solid format for commercials, for broadcasting, but that’s another super fragile format that they can barely save anymore.

We got very few commercial projects, actually, but I had to go to work, 40 hours a week, one hour for lunch, so I got busy and made cartoons.

One thing that was so different is that Gregg didn’t care about owning anything I did. I had signed no contract; there was no, “All of this belongs to me,” which is everywhere now in the business. When my films were finally finished, he still didn’t want to own them! They were my films and I’d made them there. It was a wonderful arrangement.

Connie Shoes commercial designed by Sally Cruikshank in 1972

What was animation like then, in the 1970s? How did the industry seem to you?

The industry was mainly down in Southern California, really. In Northern California we were so out of that. There was so little production going on there. Gregg was doing commercials, but it was more just art. I felt I was an artist experimenting with things. The scene in LA was very male-dominated, and in San Francisco there was very little animation going on.

I mean, there was one little company called Imagination, Inc. which was doing work for Sesame Street and they did some shorts with Lenny Bruce that were kind of famous. They tried to get me work, but nothing came of it. I submitted some designs for Sesame Street and they were all rejected. I was just really lucky to fall into the situation at Snazelle. I didn’t have much contact with other animators or anyone else in the animation business except when we would take our commercials to LA to be photographed and then you’d have to deal with the male crews at animation camera services, which was just how the crew scene was.

Was there anything you were trying to do specifically, or were you just experimenting?

As incredible as it may seem, Gregg thought that I may be able to figure out how to do 3D without glasses! Well, I was the most ill-suited person for this, because I don’t think I even experience 3D that well. I played around with that, but I think he just liked the idea of animation. He saw something in me, and saw something in animation in the future and he wanted to encourage me. He did hire a lot of young people, but it was more for cheap labour. Enthusiasm and cheap labour gets you a long way with crews!

Your first film there was Quasi at the Quackadero, right?

At Snazelle it was, yes. But I’d already made those other films, Ducky, Fun on Mars, and Chow Fun. Quasi at the Quackadero was the first one there, and it took two years.

Sally Cruikshank's award-winning short film Quasi at the Quackadero (1975), featuring talking ducks, robots, and an amusement park in the future.

The animation cel process was so labour-intensive and tedious. It was kind of phenomenally difficult. Really hard if you were entirely on your own. I hired a lot of friends to paint cels. You just had to ask for favours. Everybody was so poor! I was paying them like 50 cents a cel. People were able to live on a fairly small salary then. I was living on a small salary myself, at Snazelle. It wasn’t like he was paying me very well, but he was paying me enough that I could rent an apartment and come and go to work.

Some of the characters for Quasi had been evolving over the years. But I got a lot of inspiration from Winsor McCay who was having a revival then, they were reproducing some of his comic strips from the early days. I re-read a lot of Carl Barks duck comics, Uncle Scrooge and Donald Duck, to try to develop a storyline. I was also living with cartoonist Kim Deitch and I knew a lot of underground cartoonists, so there was a lot of conversation. Everyone was excited about discovering things from the past, I’d say.

I have a lot of my early sketches and storyboards. Things from Quasi. I have a lot of material. They have never been reproduced, in fact.

Tell me about the voices in these cartoons. Did you use your own voice?

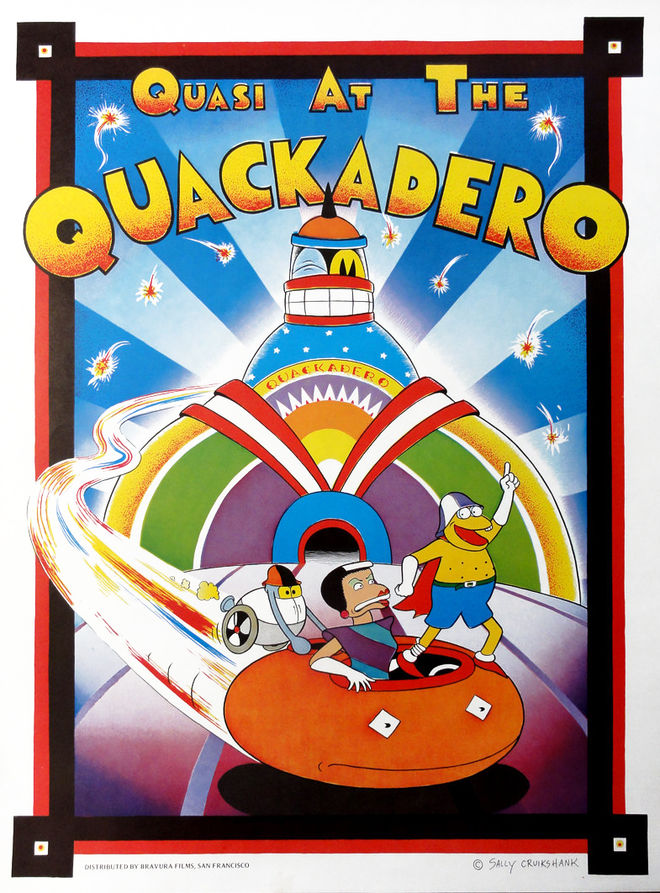

Promotional poster for Quasi at the Quackadero by Sally Cruikshank, 1978. Available for purchase.

Yeah, but not because I wanted to! But yes, I did a number of voices. Al Dodge did some voices, Kim Deitch did some voices too. It was a matter of asking friends to help out, not real paid talent. Through all the cartoons I’ve done, voice work was always the most problematic. I can hear it in my mind, but... I can’t necessarily do it and I can’t necessarily get other people to do it, either! Some of them I recorded in my closet in my apartment, haha! Then we also recorded some at Snazelle on regular recording equipment. And the music was recorded in an actual studio.

For the music in Quasi, I was already about halfway through when I met up with Al Dodge and Robert Armstrong and talked to them about doing the track. They were real keen on doing it. They saw pencil tests and did some demo tapes, then we refined it. We went to a recording studio in Berkeley called Sierra Sound and recorded the music there. So I didn’t have the chance to animate to the music, but I adjusted it a little to make it work.

What did Quasi mean for your career? How was it received?

Initially, it was not received that well. Especially by traditional animation distributors. I can remember, I thought the International Tournée of Animation would take it, and they said they hated it! They wouldn’t take it. Independent film people liked it a lot, though. It went to the Ann Arbor Film Festival, and I think it won a prize there. And then it just kind of picked up! I shot it in 35mm, so I was able to rent it to theatres and they would get really good reactions to it at midnight shows. They had midnight shows then, and it played a lot around the Bay area and started to go to other parts of the country. It was very popular in Boston, at a place called Off The Wall Cinema, that people remember very fondly, though I was never there. It just seemed to be really taking off. I got a lot of rentals, film festival requests, and so on.

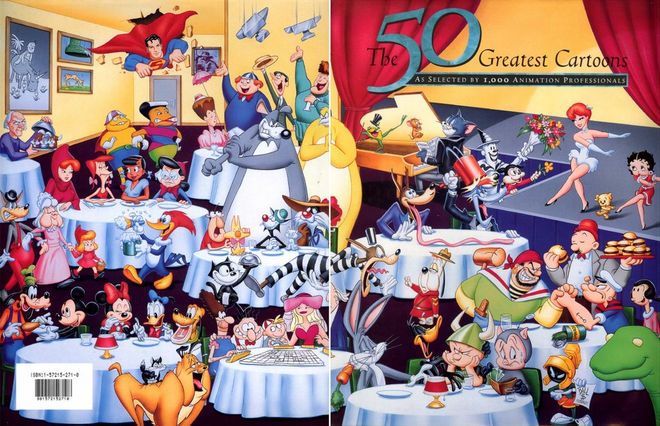

And it was included in that book, The 50 Greatest Cartoons.

Right! The distribution model then made it more possible for one film to be seen so widely.

The 50 Greatest Cartoons: As Selected by 1,000 Animation Professionals book cover featuring characters from highly regarded animated short films made in North America, including Quasi and Anita by Sally Cruikshank (left, near top)

That book was sort of an outgrowth of a group following a magazine called Mindrot. It was kind of indicative that younger people were catching on to my work and others' and really liked it. There were so many independent and 16mm screenings going on in colleges all over the country.

In the days before VHS and DVDs, people went out to see weird shows, they didn’t just rent them. They didn’t just look at YouTube. And libraries were buying prints! And people would borrow them and have little screenings.

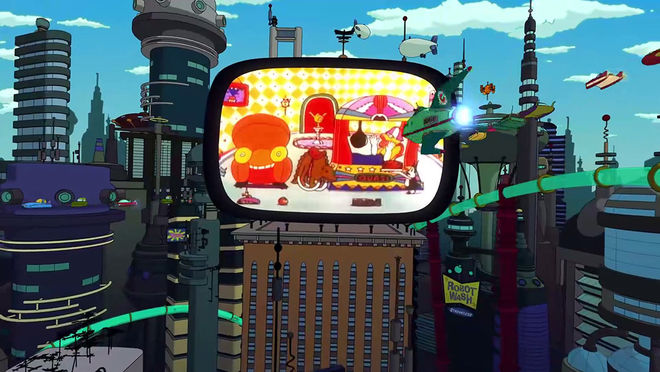

More recently, in 2008, a clip of Quasi at the Quackadero was featured in the opening of Futurama: Bender's Game. It seems like the animators were inspired by your work. What did you think of that?

Well, I like Futurama ’cause they paid me! I knew they had used a clip but I never saw the show. It's at the beginning, just a quick clip on a zoom-in through the city. The rest seems more like Yellow Submarine to me. And the characters are all striking those TV show poses.

The opening title sequence to Futurama: Bender's Game (2008). The cartoon on the Jumbotron is a clip from Sally Cruikshank's Quasi at the Quackadero.

So coming off of Quasi, what did you do next?

So then I made another one! Make Me Psychic. It actually opened with China Syndrome, which was a big film in ‘78. Jane Fonda, a nuclear meltdown. It opened theatrically, so that was very exciting for me. I was getting better at my own little company of distributing the films, just hauling them off to the post office and so on. I was picturing that I would be making a whole series of shorts then, I’d find some way to revive the theatrical short. It didn’t happen, but that’s what I was hoping! Make Me Psychic was again very popular. Again, I paid friends to paint cels and do the voices. I animated to the music, so it has more of a musical sense to it.

Clip of Sally Cruikshank from the PBS documentary The Animators (1982), about San Francisco-area animators. The documentary also features Marcy Page, Jeff Hale, Bud Luckey, Rudy Zamora, John Korty, Vince Collins, and Drew Takahashi.

It all seemed like it was really taking off and Snazelle even hired a press agent for me. There would be little TV featurettes on me in the Bay area. There’s one on YouTube where I’m talking about animation.

Then I got a grant to develop a feature! It seemed like that was the only way to go, because I could see that shorts… I was trying to get people to back ‘em, but it just wasn’t going to work. So I tried to do a feature. I made the Quasi’s Cabaret trailer, as if the feature existed, to try to pitch and prove it. As if it was a coming attraction. It was fun to make in itself. I designed the whole thing, I storyboarded the whole feature. I have all the storyboards.

But it didn’t make it? Why do you think that was?

I don’t know, I went around trying to sell it but there wasn’t much interest.

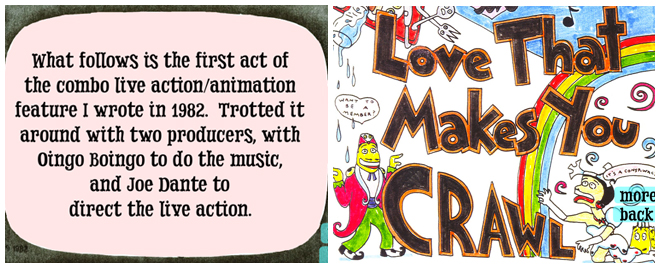

And then I started writing another script. By that time, I was living in LA and I had this other project. I drafted storyboards for an animated/live-action feature that I wrote. It was 1982. These producers were determined to make it work.

Storyboards for Love That Makes You Crawl, a live-action/animation feature pitched by Sally Cruikshank in 1982. See the whole set.

That was how I met up with Danny Elfman. [The producers] had a connection to him. They said, “We would like you to do the music on this feature if it ever gets made.” And that one got closer to being made, but didn’t quite reach it, either.

Danny Elfman actually said that in the ’70s, he and his band Mystic Knights of the Oingo Boingo used to run Quasi at the Quackadero as their warmup act before shows in San Francisco – but I didn’t know that, because I didn’t go out at night!

Image Set: Original animation cel setups from Face Like A Frog.

So then, he scored the short I made, Face Like A Frog, for free. He was also learning how to score music, so it was sort of an experiment in exchange for running my short so many times.

Do you think you’d ever come to back to Quasi’s Cabaret and make the full movie? Is that something you still want to do?

No, I don’t think so. All the feature projects that I had were appropriate for the time but wouldn’t seem appropriate now. Features are too hard, and people aren’t doing that kind of animation anymore. Animation has changed so drastically, even just in the last four years, as everything has gone digital. So no, I’m done with that. I like the physicality of the earlier cel method, not that I haven’t spent many many hours on Flash.

What came after the trailer for Quasi’s Cabaret? It was the beginning of the ’80s. What was going on for you at that time?

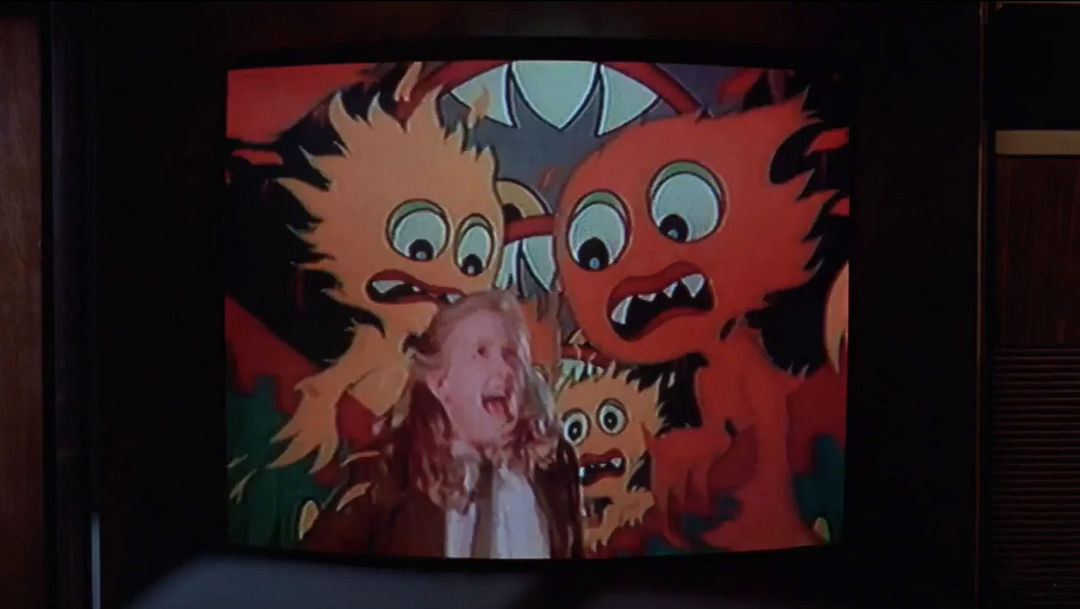

Oh, yeah, well! I met my future husband, who was producing a segment of Twilight Zone: The Movie, and I was hired to design and direct the animation in Joe Dante’s episode. This girl is put into cartoon hell. And the girl – Nancy Cartwright – ended up being the voice of Bart! That was really fun. I didn’t do the animation, I did the design and direction. A very good animator named Mark Kausler did the animation, did a fabulous job, and Mary Cain, a wonderful ink and paint artist, painted all the cels.

Image Set: Original animation cel setups from Twilight Zone: The Movie (1983). The images consist of four animation cels taped together, with a color ade paper background (purple or blue). These cels were designed by Sally Cruikshank, inked and painted by Mary Cain, and then animated by Mark Kausler.

It was an interesting project because it was using live action and animation, with a live character in a cartoon setting. It was more often that you’d see a cartoon character in live action, but this was a little different. This was before Roger Rabbit.

So it came ahead of that whole wave.

Yeah, people weren’t sure it was going to work, even. We had to ask a lot of questions to get that working.

Clip from Twilight Zone: The Movie (1983) featuring an animated sequence by Sally Cruikshank

I think it was done with green screen and then the director saw a pencil test through a viewfinder – maybe it was on a monitor – while Nancy was acting, so you could see she was in the right place, it was all gonna work right. It was tricky.

After that, you worked on Top Secret! a little, right?

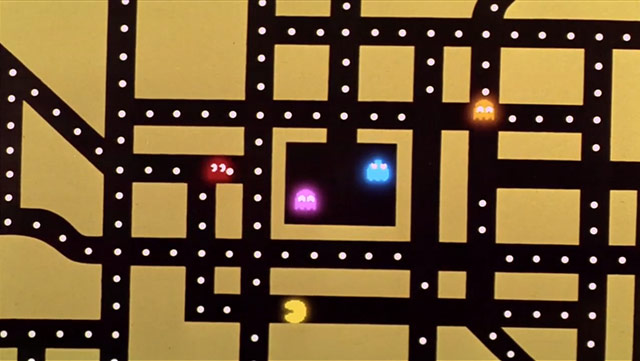

That was just a little bit of animation. Just a Pac-Man piece, just a gag.

Animated Pac-Man gag from Top Secret! (1984) designed by Sally Cruikshank

My husband was producing the film. We were over in England so I got to know Jerry and David Zucker and Jim Abrahams and it seemed like an easy enough thing for me to be able to do. And it was because I did that that I got the Ruthless People titles job.

And then you broke right into title sequences with that…

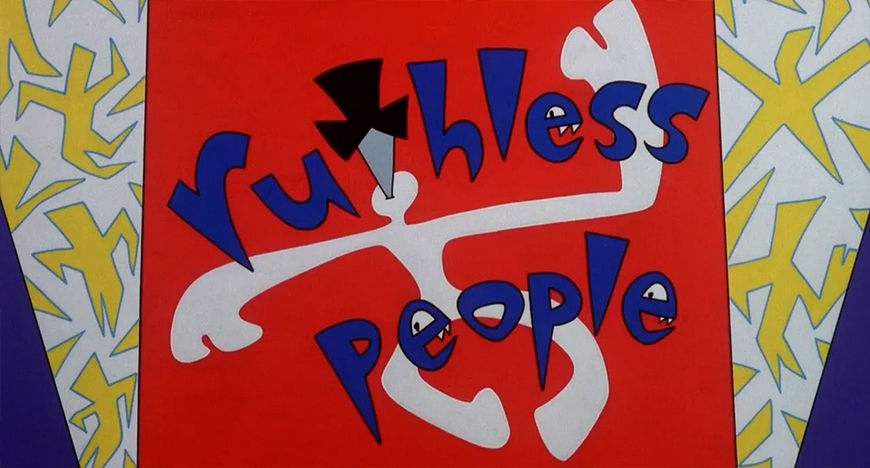

Yeah! Ruthless People was the first major film sequence I did. I mean, I’d done titles for my own films before, but that was all. I thought I wouldn’t be able to do it but I enjoyed it a lot. I struggled doing the titles on my own films.

As I recall, I went in to talk to them about the titles. They did a screening of the movie and I thought, “Oh, this is great.” They said, what we want to do is a cavalcade of ruthlessness through history. And I thought, “No!” I was so struck by the Memphis Design in the movie. So I said, you know what you should do is you should treat the piece so that every title is treated ruthlessly and include the design of this crazy furniture that the wife in the movie is buying – which is Memphis Design – and then the production designer loaned me a book on Memphis Design and I was off and running! It works particularly well, I think, because the directors were so gag-sharp. They would throw out concept after concept until they had exactly what we wanted. So we really refined each individual credit more than most directors would have done.

How did you set about developing it? Did you storyboard with them?

Yeah, I storyboarded it and then I needed a production company so that’s where Playhouse Pictures came in. They were a long-established TV commercial company. I was looking at their history recently and even Saul Bass worked with them. I know you’ve done lots of pieces on Saul Bass, and back in the ’50s he did black and white commercials with many famous animators. They’re very friendly people. Their father, Ade Woolery, was the very first multiplane camera operator at Disney.

So, anyway, they had many contacts with animators which was needed. I designed it, I laid it out, and then I talked to Gerry Woolery about what I was looking for and he would instruct the animators. They would do the animation and bring it back, and we would criticize it, change it. That’s how it went.

Ruthless People (1986) main titles by Sally Cruikshank

But Disney was fussy, really fussy! They had so many legal restrictions on everything. Everybody’s title had to be proportionate sizes to everyone else’s by contract. There were just all these legalities.

What were you using to animate?

Well, it was pretty much the same for everybody in animation at that time. It was just pencil and paper in the storyboards, and just watercolour markers because I didn’t like the way the AD markers smelled. So the animation would all be done in pencil, then it would be photographed according to an exposure sheet, and then once approved, the ink and paint began on animation cels. That’s a long and tedious thing when all the cels are painted and cleaned and then they’re photographed, one by one, according to the exposure sheet. And that’s the end of the art process!

The "Ruthless People" single by Mick Jagger

And tell me about the music, that Mick Jagger track.

Oh, well Mick Jagger did not come in initially. Even though the song he sings on it is the title theme, “Ruthless People.” He stalled on it for a long time so we had to go ahead and animate it without a track, which was too bad. It would have been so perfect to hook up the music to the animation.

You may have read or heard this story, but… one time, long after, I was driving my car and I had NPR on. They were interviewing Mick Jagger for some promotional thing or book – I’ve never been able to track it down – and so I’m just driving along and I hear him say how he really hated those titles!

I thought, “Oh my God, well, I hated your song, too!”

It’s good that we’re getting that out, so he’ll know that, too.

Haha, yeah, definitely.

You also produced a commercial for a product called Candilicious around this time, didn’t you?

Yes, actually Candilicious was right after Ruthless People. Gerry Woolery and I were flown to New York for a meeting, I think it was at a big agency, well, it must have been if we were being flown around like that. I'm guessing it was 1987 because I went to a high school anniversary right after New York and I graduated in 1967 so that would have been 20 years.

Candilicious commercial designed by Sally Cruikshank in 1987

I designed and directed it. It was done at Playhouse Pictures. I liked the animation but the candy wasn't so tasty... and normally I like gummy candy, like Rowntree's Pastilles and such. I think the candy had a problem because it was chewing gum that you swallowed! The product never took off.