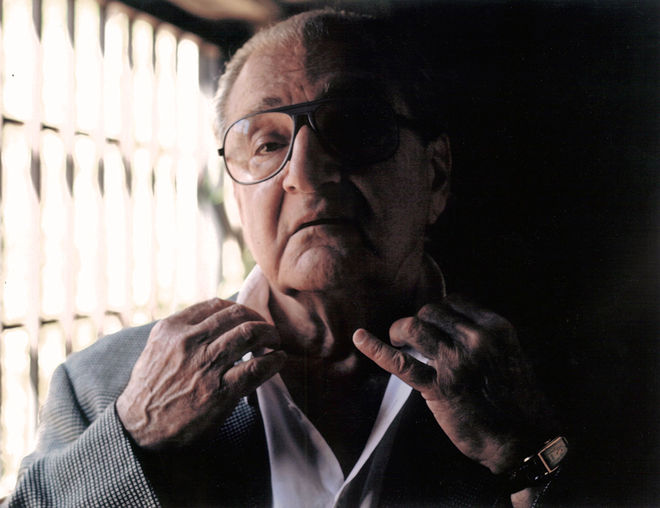

Sandy Dvore is perhaps best known as the designer of the iconic opening of The Young and the Restless, or for his walking birds, the multicoloured covey of partridges in the cheerful opening of ABC’s The Partridge Family. But Dvore is a living legend, one of those Hollywood greats with a career spanning 30 years. He is an actor, an illustrator, a graphic designer, and a title designer with more than 70 credits to his name in the fields of film, television, and advertising.

But there were a great many false starts and pivots along the way. When Sandy Dvore left Chicago and headed for California in 1958, discouraged by the Michigan Avenue advertising circuit, he was inspired by Marlon Brando. He was going to become an actor.

Title Designer Sandy Dvore

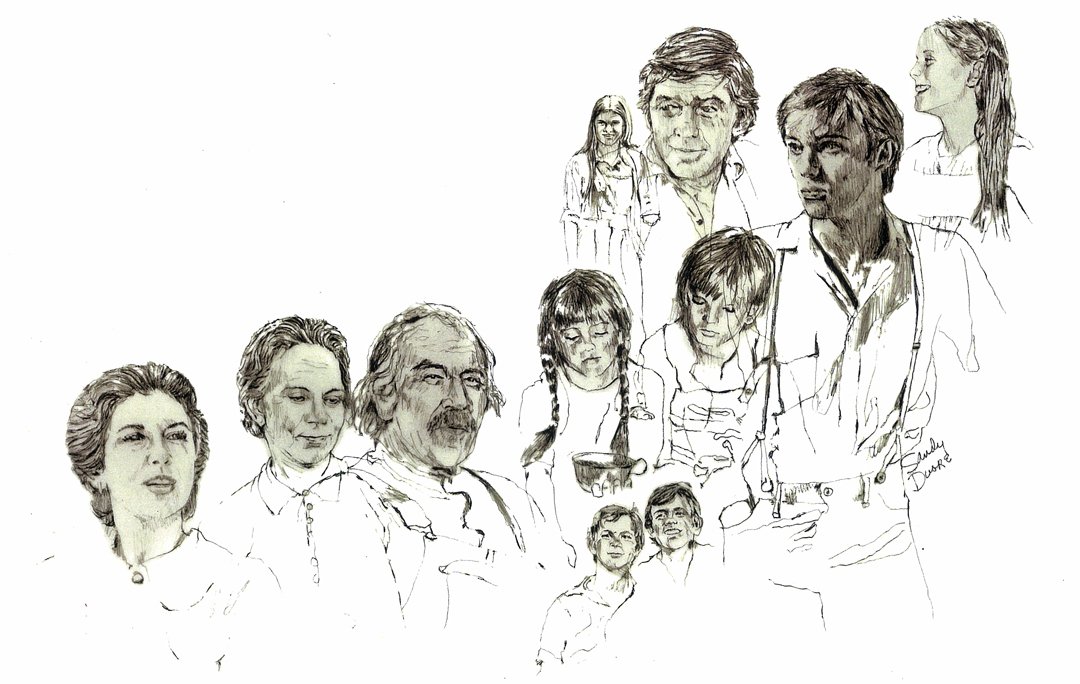

Instead, he was discovered by film industry publicist Warren Cowan who hired him to illustrate a trade ad for Sammy Davis, Jr. Dvore would go on to illustrate hundreds of ads for stars like Frank Sinatra, Liza Minnelli, Natalie Wood, David Bowie, Mick Jagger, Judy Garland, and Steve McQueen. His minimal but vibrant illustrated trade ads held the coveted back pages of The Hollywood Reporter and Variety for years.

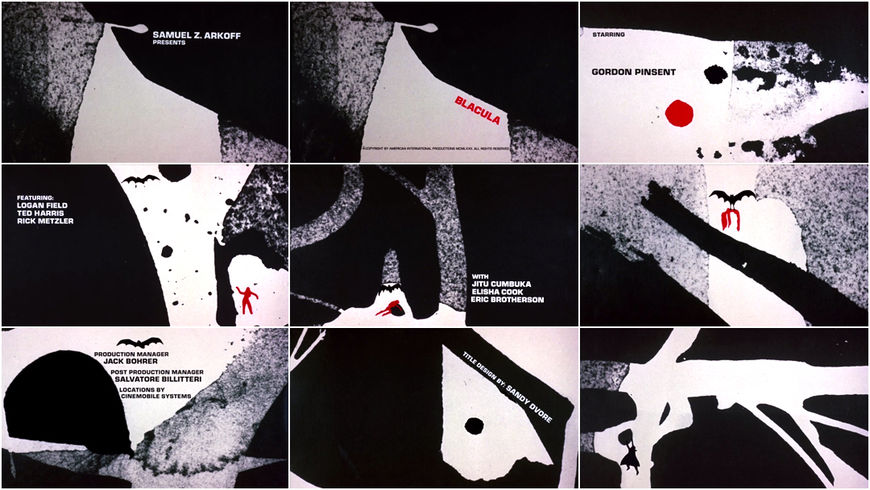

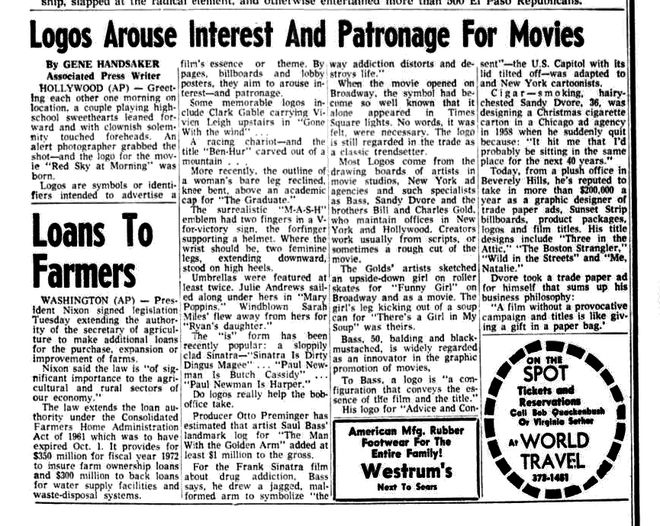

He also worked as a graphic designer, creating album covers for recording artists and posters for films, as well as corporate logos for United Artists, Lorimar Television, American International Pictures, International Creative Management, and Solo Cup. However, it’s as a title designer that Sandy Dvore has made the most indelible impression, creating iconic pieces of television and motion picture history. Beginning with the “special title art” of 1968 film Wild in the Streets, Dvore has designed title sequences for films including Skidoo, Three in the Attic, De Sade, The Dunwich Horror, Blacula and its sequel Scream Blacula Scream, as well as television series The Waltons, Skag, Falcon Crest, and Knots Landing. In 1987, he won the Emmy for Outstanding Graphic and Title Design for his work on the Carol Burnett TV special Carol, Carl, Whoopi and Robin, featuring comedy greats Carol Burnett, Whoopi Goldberg, Carl Reiner, and Robin Williams.

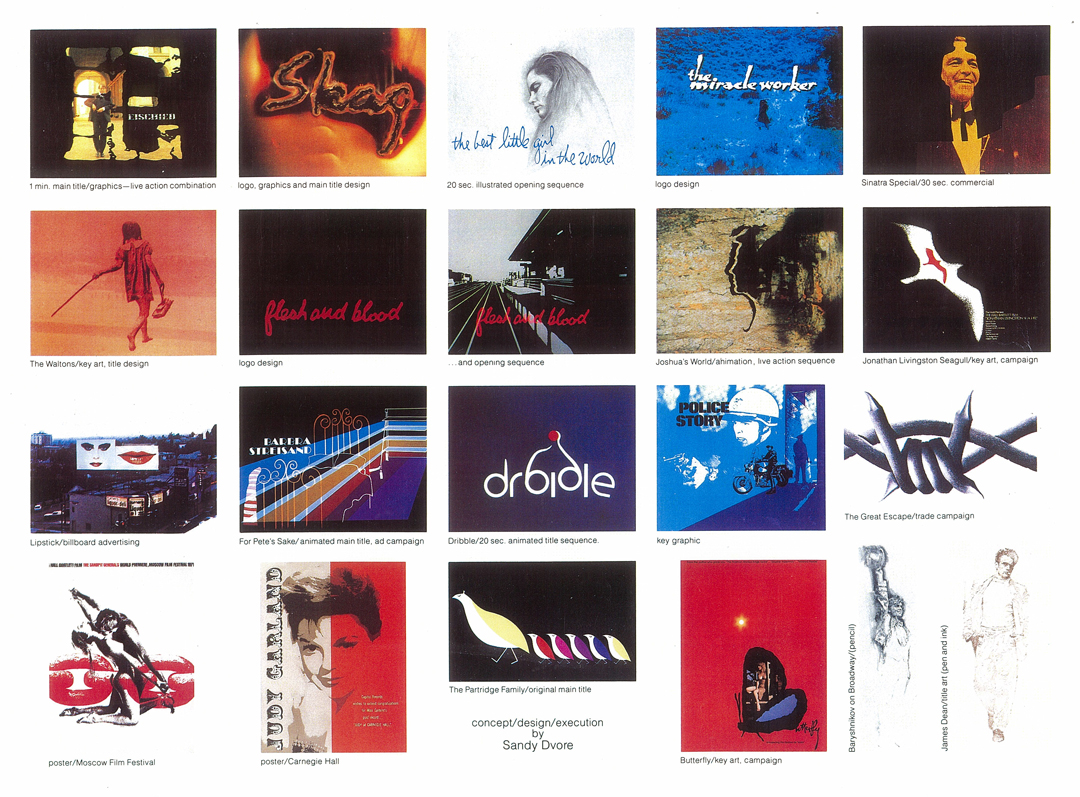

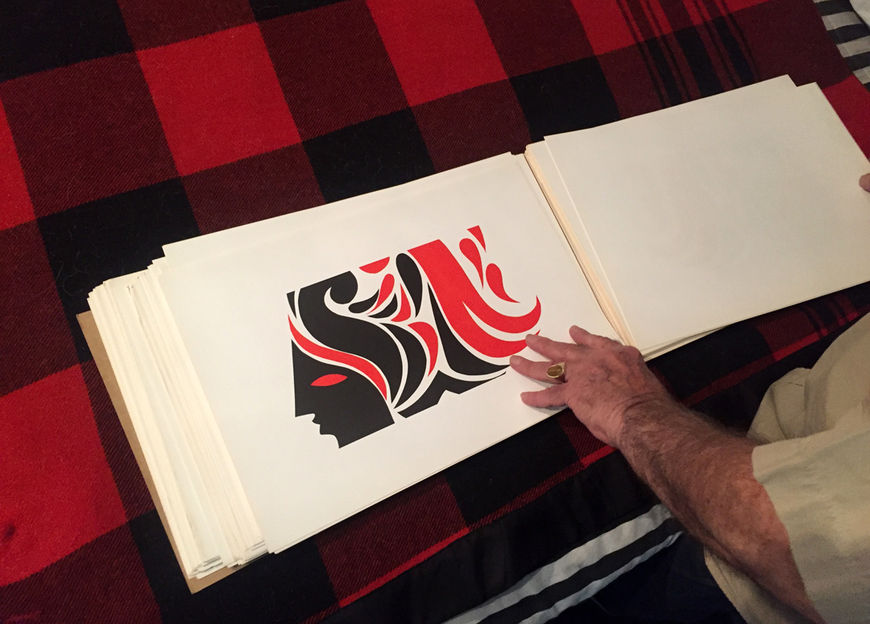

Samples of work by Sandy Dvore including title artwork for Eischied, Skag, The Best Little Girl in the World, The Miracle Worker, The Waltons, Flesh and Blood, Joshua's World, Jonathan Livingston Seagull, Lipstick, For Pete's Sake, Dribble, Police Story, The Partridge Family, and James Dean; and commercial artwork for Frank Sinatra, The Great Escape, The Moscow Film Festival, Judy Garland, Butterfly, and Baryshnikov on Broadway.

Dvore’s style is one of constant flux, often involving hand-drawn lettering and the colours red, black, and white, and moving variously between strong graphic shapes, detailed graphite portraiture, bright splashes of paint, and charming cartoons. Dvore’s use of graphic abstract forms appears in many of his works, first in the flames and flag of Wild in the Streets but popping up later in the openings to films De Sade, The Dunwich Horror, The McMasters, and Blacula, and TV series The Partridge Family, Getting Together, and even – 15 years later – 1987’s Sable. In his title designs for Spenser: For Hire, Knots Landing, A Hobo’s Christmas, and Wolf, Dvore uses splashes of paint. In the openings for James Dean, North and South, The Young and the Restless, The Waltons, and Jennifer Slept Here, he uses detailed graphite and ink illustrations to depict the show’s key players. The openings for Little Cigars, Two on a Bench, For Pete’s Sake, and The Seniors feature warm and delightful cartoon renditions of cigars, Barbra Streisand, a pair of lovers, and a lecturing professor, respectively. Many of these sequences also feature Dvore’s handlettering, a loose and open script drawing out the logo of The Young and the Restless and the titles to Spenser: For Hire, Knots Landing, Wolf, and Kung Fu: The Movie.

Sandy Dvore’s work is diverse, a motley assortment of techniques and media. It doesn’t have that consistent sense of personal brand which allows some designers to become household names, but then Dvore is not that kind of designer. As David Bushman, curator to the 2010 exhibit at the Paley Center said, Sandy Dvore is “the guy who did new.” He made his design debut in Hollywood 50 years ago, but his work continues to make its mark and delight new audiences. C’mon, get happy!

A visit and discussion with Title Designer SANDY DVORE in his West Hollywood studio.

Thanks so much for your time today, Sandy.

SD: Sit down! Enjoy yourself. I'll answer anything that you want.

So, you've been an actor, a designer, and an illustrator, working in film, television, and advertising. How did you get started?

SD: Well, I was going to leave Los Angeles, 'cause I wasn't doing very well [as an actor]. Warren Cowan, who was this great press agent, he asked if I could draw Sammy Davis, Jr. So I did it, 'cause I needed $100. But somebody else saw it and three months later I was the hottest thing in town. And then I got with Mr. Sinatra and his people, started doing all his stuff...

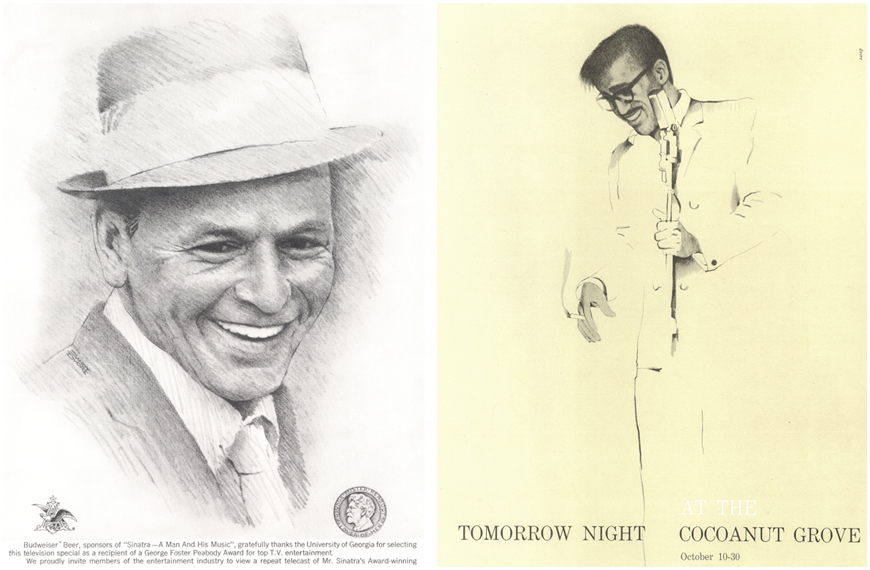

Image Set: Trade ads drawn by Sandy Dvore for Sammy Davis, Jr., Frank Sinatra

A wall in Sandy Dvore's studio displaying illustrations, title artwork, and trade ads

Sandy Dvore looks at slides in his West Hollywood studio, 2016.

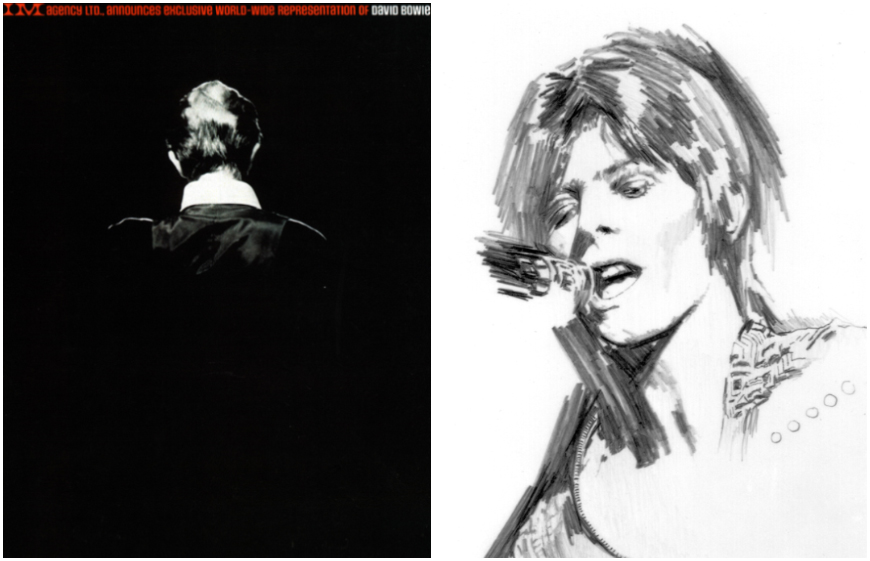

SD: I mean, I had everybody – Debbie Reynolds. Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass. Bowie! Pencil drawing of Bowie. I did a lot of ads for Bowie.

Did you meet him?

SD: Oh, sure. In his bib overalls, and his checkered shirt. I’ve got… I’ve got the drawing of him and I got the thing I did with the back of his head. But he was very, very nice guy. David Bowie was highly appreciative.

Ads for David Bowie by Sandy Dvore

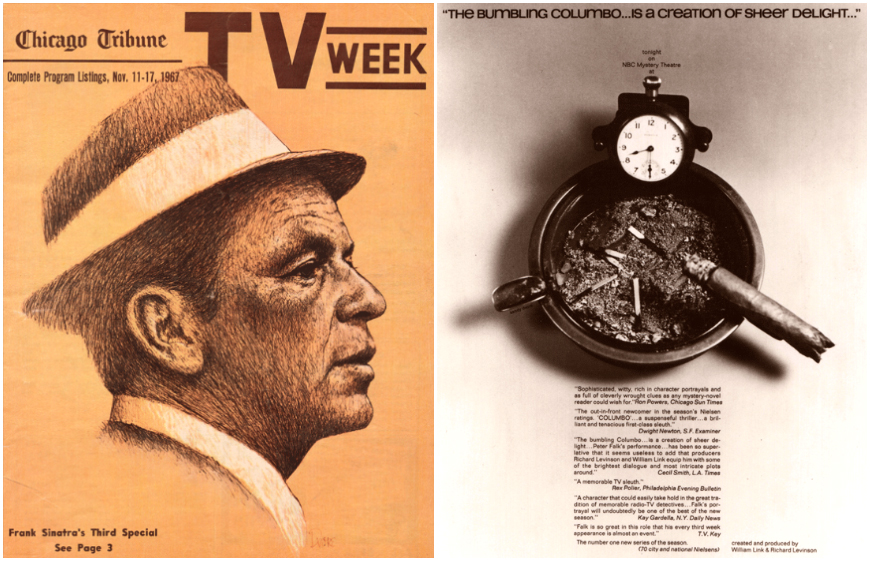

SD: But the big ones were always appreciative! I mean, Sinatra always wrote me a nice letter when I would do something for him. A nice note. This is Columbo!

Ads for Frank Sinatra and Columbo, illustrated, photographed and designed by Sandy Dvore

SD: This is my father's ashtray from his store in Cicero and it had a clock on it so I could show what time the show went on, on the clock, get my father's ashtray in front of everybody in show business, and stick Columbo's cigar on it and make it all work.

—Sandy DvoreI always had the complete idea and saw it before I put the phone down.

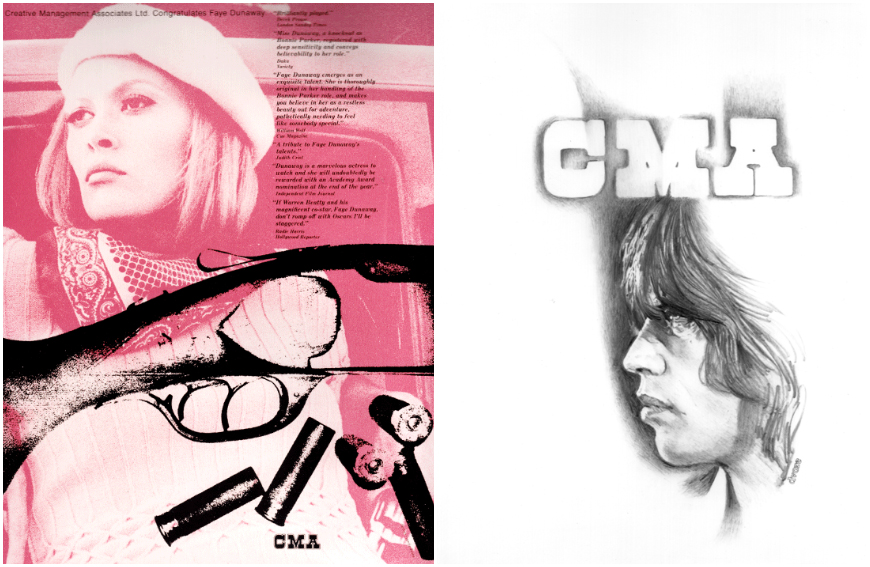

Ads for Faye Dunaway and Mick Jagger, illustrated and designed by Sandy Dvore

SD: Johnny Mathis at the Sands in Vegas. Mick Jagger! Signed with CMA. Then... I got involved with films. Lawrence of Arabia, Omar Sharif. I did Miracle Worker. Klute. Butterfly. Camelot. Sinatra.

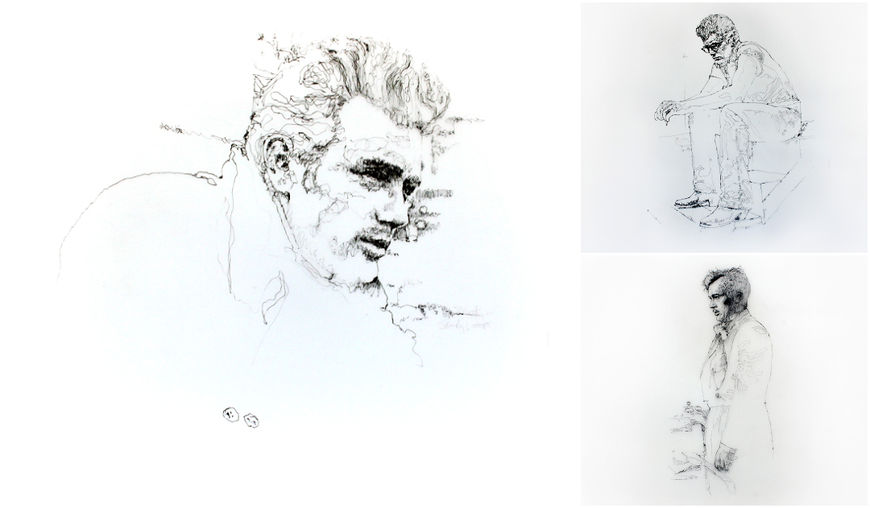

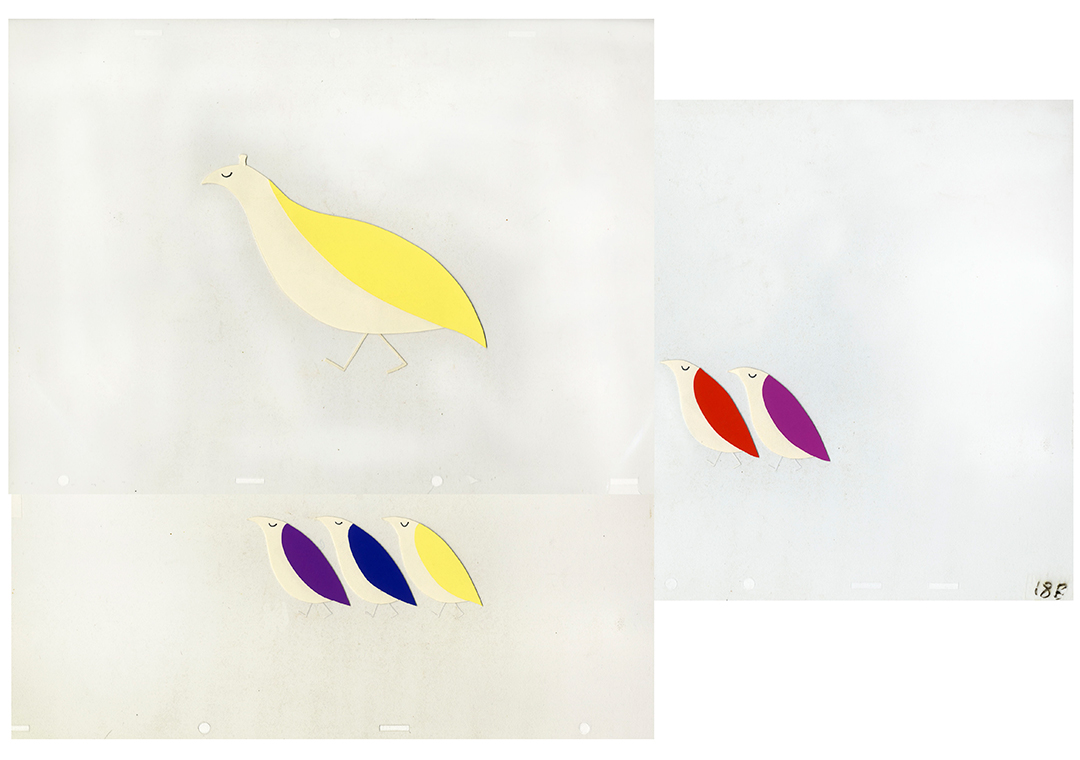

This was for the opening main titles of James Dean, 1976. I did it all in drawings. And this is one of the drawings for the opening main title... the James Dean thing.

Original title artwork from James Dean TV movie (1976), created by Sandy Dvore

I think I was the only one at the time who could take individual card credit for titles on the screen. It was always “Titles by... Executed by... Production by” it was always six or seven things, in that below-the-line, that they call now, but I took individual card credit. This came off of Evergreen. For Evergreen, I wanted to do drawings of the people. I wanted to give it an old-fashioned look.

Credit for Sandy Dvore in the main title sequence of Evergreen

You’re originally from Chicago, right? Where did you go to school?

SD: Yeah, Chicago. After high school, I went to the University of Illinois. I entered pre-med. Because where I came from, the only person in the family who got an extra dose of respect was my uncle, the doctor. I wasn't a very good student. And in the middle of the semester – now I'm remembering everything so this could be a long interview! [laughs]

Bring it on!

SD: So, we were given the task of drawing the bones and muscles of the human anatomy. So I got some paper and some coloured pencils and I did it. And this professor came up to me with these drawings and he said, “Did you do these?” I said yes. And he says, “Then you're in the wrong lecture hall. Take these and walk over to the art building, and you tell them I said that's where you belong.” So I did. I transferred into the art school but all the classes were taken up… and the art school was in the architecture building. The tables were all flat. It wasn't very “arty”. I sort of flunked out.

So I came back to Chicago and I enrolled in the Academy of Art. There I got it. I spent... 1953 and ’54 at the American Academy of Art, did well, and then there was a year or so left that I could finish up with transferred good grades, and I went back to Illinois. Then when I came back to Chicago, I got an apprentice job. With Leo Burnett advertising. That was considered a big deal. Leo Burnett was like the big new name in Michigan Avenue advertising. J. Walter Thompson was the standard-bearer but Leo Burnett, they were comin' up with things like Kellogg's and the Jolly Green Giant and new packaging for Marlboro.

I was made an apprentice and I was given a cubicle and I was thrilled to death to get this job. I was supposed to act like an apprentice – cut mattes, staple things onto boards for the creative meetings... but I had no desire to do that. There was another apprentice there, and he seemed to enjoy cutting mattes and papers and cleaning brushes and sweeping up. Until one day, while cutting mattes, I heard a big commotion. I'll never forget it. He cut the tips of his fingers off! And he was rushed to the hospital. And then I felt more justified in not wanting to cut mattes with number eleven x-acto blades, so I sat in my cubicle and I did Dole pineapple. I drew a man with a sombrero with a big moustachio and I had him on a one-wheel. Remember the one-wheel bicycles, with the big one wheel and the little wheel in the back? But I made the big wheel a slice of pineapple! [laughs] Full-page ads that were gonna go into the creative meetings. I was really knockin' out some good stuff, you know? I wanted to get in on those creative meetings. I wanted to run the creative department.

—Sandy DvoreI had seen this movie a few years before – On The Waterfront. That had changed everything for me.

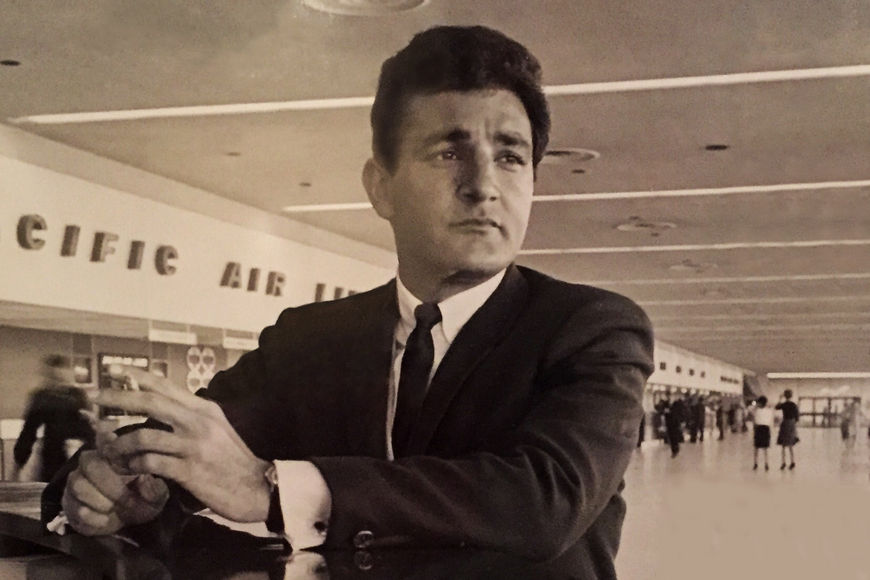

Sandy Dvore c. 1960s

SD: But one night after a baseball game against J. Walter Thompson down at Grant Park, I came back [to the office] to change clothes, and I saw the artwork that I had mounted for the creative meeting broken in half and put into the garbage. The art director on that floor was a short Irish guy who – by that time in the evening, I would've been home, but we'd played a game, so I was still downtown – and his face and his nose was all red. He had done his martinis for the night. I asked him why my stuff was in the garbage can. And he said, “Because I'm not gonna let any snot-nosed little shit come in here and become a star when he's supposed to be sweepin' fuckin' floors!” So... we got into it a little bit! [laughs] And um... I was let go.

So then I went over to CBS 'cause down deep I always wanted to be an illustrator. I got a job doing these [ads]. Television was black-and-white, and we would get prints from Hollywood, 8x10 photos, and there was a hot press machine, where you press down and put the type in. Regular type that you picked out piece-by-piece, heat up, and print the name. We had to knock out seven or eight a day. But when I got Lionel Barrymore... and when I got Donna Reed and when I got all these wonderful people... I just couldn't see myself using an old picture sent from some office somewhere and putting hot print on it. I had to draw them and design them and do watercolours of them... But the guy called me into his office and said, “The work is great, gotta let you go!” So they fired me.

"He's a University of Illinois graduate and he went to work for an advertising agency where he tried to change the image of a major cereal manufacturer. 'The problem was they didn't think a kid just out of college and earning $65 a week should do that.'" August 17, 1974, Kenosha News

SD: Chicago's sort of a small town, everybody knows everybody else's business – I figured, if this is gonna keep happening, what am I gonna do? I remember that I had seen this movie a few years before – On The Waterfront. That had changed everything for me. That was where the world was going, as far as excitement was concerned. There was no more of the Clark Gable and the George Montgomery movies. So I called a girl I was close to at the time, and I said, “Do you wanna go to California?” I had a little money saved up and I bought a '57 Chevy convertible. I left home I think in March and headed for California. Started out in Westwood, living with Cos Johnson, the brother of Arte Johnson, the comedian. Then I moseyed up and met some people in Beverly Hills. I started drifting up to Sunset Boulevard and hangin' out at the coffee shops, meeting actors. I started to get to know 'em, hung out with people like Robert Vaughn, who was there, wearing an ascot and a blazer, and playing 1930s movie star... he always dressed like a movie star. Everybody else had blue jeans and was drinking wine, but when he came in, wearing ascots and blazers... he was a movie star. And Suzanne Pleshette, and Sally Kellerman was the waitress. Warren Oates was sitting in the back with his bottle of wine. I met a girl there... Madlyn Rhue, who was an actress, a dark-haired actress. She was a good girl. She died young, from MS. She's one of my fondest memories.

So, I hung around for about four years and I got a few jobs when I'd get hungry but... I knew I was gonna get fired. So I would go to work, like at Weinberg Advertising. After a week I wouldn't go back after lunch, because I had fear that I wasn't gonna make it. Wasn't good enough. I tried to start a little business on my own, and that didn't work. But people started to know me a little bit. I got a couple of acting jobs. I did one television show called Divorce Court. I did The Lieutenant for one day's work. I joined the union, SAG, for $60. Now I think it costs $3000! Then we started an entertainer's league... baseball.

Article from the Long Island Press Telegram from June 14, 1962 about softball team the Hollywood Entertainers, featuring players Sandy Dvore, comedian Soupy Sales, Peter Brown (Lawman), Mark Goddard (The Detectives), Doug McClure (The Virginian), former major leaguers Michael Dante and John Beradino, and others.

SD: There was a ball field on Poinsettia in Santa Monica where we played on Sundays. There was an actress out here who came from Chicago, and she said, “What's Sandy Dvore doin' out there?” And Guy McElwaine said to her – he was a press agent, he was partners with Dave Gershenson, and they represented Bobby Darin. She said, “Sandy's a great artist.” He said, “Well, you must have the wrong guy, 'cause he's an out-of-work actor.” She said, “I'm tellin' ya, I know Sandy Dvore from Chicago. He's a wonderful artist.” So after the game, we talked. He said, “If you're really any good, we take a lot of trade ads, for Natalie [Wood], for Robert Wagner, for everybody.” I just needed some money, I was so tired of not having anything.

—Sandy DvoreI was going nowhere. And here somebody offers me to do something for the world's greatest entertainer.

Ad for Judy Garland by Sandy Dvore

So I got this call to do this Judy Garland ad for McElwaine and Gershenson. I couldn't believe it because I was going nowhere. And here somebody offers me to do something for the world's greatest entertainer.

Then I got a call from this Warren Cowan, of Rogers & Cowan, and he asked me if I could draw Sammy Davis, Jr. So I did that. And while I was doing it, I was gonna order the type for Sammy Davis, Jr. – “Tomorrow night at...” And I thought to myself... in Leo Burnett fashion, in CBS fashion – the urge to become the head of the creative department reappeared! [laughs] I thought, “What am I doing, ordering type for Sammy Davis, Jr? I'm in Hollywood, I don't have to put his name on the goddamn thing! It's Sammy Davis, Jr!” It went on the back of the Reporter. Well, it came out, and they thought that changed trade ads the way On The Waterfront changed movies. It makes Sammy so big you don't even need his name, which is really what an ad is about! It was something that I could do any time, but they had never seen anything like it.

I got invited to the opening at the Cocoanut Grove, and every major player was there that night. Sammy came out and he said, “Every great once in awhile somebody comes into our industry with a gift that is special...” – and he announced me. And he had rigged it so that the big spotlight at the top of the room hit me. I was made that night.

Ads for Sammy Davis, Jr. by Sandy Dvore

SD: So then McElwaine puts together a meeting and I go see Freddie Fields. He's the most powerful guy in town. He said to me, “Kid, I represent every heavyweight in the business, and I'm gonna give you my entire client list. I'm gonna buy the back page of the trades for one year and anything that any of 'em are doing, you'll be sent over the information and you do anything you want. You don't have to come to me for approval.” He got it. He read me. He was the first person in my life who read that part of me, the artist part of me.

He really believed in you.

SD: And I tried every time to justify that. The CMA ads did become popular within the industry and everybody else started chasing me. And so I did all these people... so many of 'em.

"When Vince Edwards wanted to make sure that nobody in the New York area could miss hearing about his Copa opening, he took a full page ad in a newspaper with a head drawing by Sandy Dvore."

Salt Lake Tribune, June 7, 1966.

So whenever there was a signing or event, they would put an ad on the back announcing it?

SD: I did not know that I was part of the deal. I did not know that when they approached people like Jagger… “If you sign with us, you get a Sandy Dvore ad or drawing!” I knew that I was becoming known, I had my little niche. But I never dreamed that I was actually part of the teaser. “You're gonna get a Sandy Dvore announcement ad if you sign with us.” When I heard that, years later... I was stunned. I was so proud. Somebody said to me, “You know how much more you coulda gotten?” I says, well, it coulda made me stupid, too.

I'd sit in Schwab’s in the morning having breakfast before going to the office – my studio – and I'd see Rod Steiger, Sidney Poitier, everybody coming in, and Variety Reporter would be on the counter, right where you could see it. And the first thing they'd do is they'd walk in and they'd turn over the Reporter to see who was on the back page! I'd sit and watch 'em. To see what kinda reaction my art was getting.

The 1960s and Main Title Design

SD: After things got good for me, my father came out here, with my brother-in-law, or by himself to visit me. Otto Preminger had called me in to do that Skidoo movie. The Saul Bass stuff wasn't working 'cause they had had a beef, and he hired me for this picture. When my father came out here and walked into my office at MGM and I was working with Otto Preminger, I introduced the two of them. And Otto Preminger said to my father [does Otto Preminger impression] “It must be – I know it – that feeling when I look into your eyes – when you have a son like this.” Well, I didn't need anymore reviews or anything from that time on!

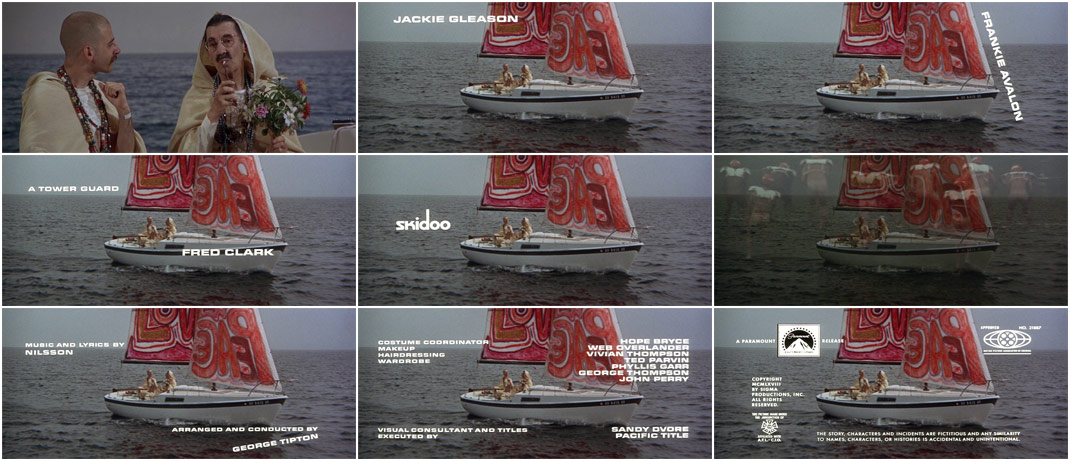

Skidoo (1968) main titles, designed by Sandy Dvore

What was working with Otto Preminger like?

SD: Well! Otto had this big beautiful office over at Paramount. Big office! He had demanded that my office be right next to his, because actresses used to come to visit me and he enjoyed all that action! He had a reputation for bein' an ogre, but it was a false thing, it was a performance. He was a great actor. He was really the sweetest of all people and a good friend. I remember when I was a kid, whenever I would go to the State Theater in Chicago, or the Marbro, that still had those gorgeous boxes upstairs like old opera houses. When I would go in there and I would see, “OTTO PREMINGER PRESENTS” I knew somethin’ good was comin’. So when I got a call asking, “Would you agree to a meeting?” Would I?! Otto Preminger, Jesus! [laughs] So, he was very much the baldheaded, blue-blazered, shirt-and-tie Otto Preminger.

So we made the deal and he said, “Now, I would like to have you come with me to the sound room and I’ll show you the picture. See what you think.” And I had been used to The Man with the Golden Arm, In Harm’s Way, Exodus... So all of a sudden this thing starts – [sings] bum bum bum! This wild, happy music. The picture started right away, because there were no opening credits. There was one little cartoon of a character in a striped prison outfit.

You didn’t draw him? Where did he come from?

SD: No. He was made by somebody before I was brought in and it was just still. I said, “You can’t have the little guy just standing there. Don’t you know what “skidoo” is, Otto? Skidoo is a word that came from “23 skidoo”, it’s from the twenties. It’s the Charleston era.”

So he says, [does Preminger impression] “So, Deevore, what am I supposed to do with him?” I said make him Charleston. “Have him come down with a little umbrella like a parachute, so he lands softly, and then have him start dancing to the music – skidoo! Skidoo! Skidoo-be-doo-be-doo.” So he says, “Can you dance that dance?” I says yeah! He says, “Good!” He takes out a camera, 35mm at-home camera. He says, “So do this skidoo, and then the little man will do the skidoo.”

—Sandy DvoreSkidoo, to me, was more than designing a main title. Skidoo was the memory of something marvelous.

Still from the Skidoo main titles featuring a cartoon character doing the Charleston

They animated based on you?

SD: Yeah. [laughs] I’ll never forget it. I said, “Have you got enough light in here for that camera?” [laughs] He looked at me. And he puts down the camera, he says, [does Preminger impression] “Deevore, are you asking Preminger if he has enough light to shoot a picture of you dancing? You are asking Preminger?” and we started laughing. We put on the music and I danced the Charleston. And Chuck McKimson animated it at Pacific. So… I made the little guy dance by doing the Charleston. I animated the lettering to human movements.

But when I saw the picture, I didn’t know what he was tryin’ to do. It was like a whole psychedelic thing! And I was sorta disappointed.

You didn’t like the movie after all?

SD: No, not particularly.

How did you work on the end titles? Those are a lot of fun – with Harry Nilsson and that song.

SD: Well, that’s what I did. Harry was a good guy. I worked with a lot of good guys. Harry sort of reminds me of Bowie. Humble. The movie had already been shot. And then… he had made up this thing – [does Preminger impression] “to not leave the theatre! Because we are going to show you who was in this wonderful thing so stay in your seats!” So he had the shot of the sailboat, with Groucho and the music.

Skidoo (1968) end title sequence, introduced by Otto Preminger, designed by Sandy Dvore and sung by Harry Nilsson

Whose idea was it to sing the end credits? Where did that come from?

SD: Otto, probably! No one else ever did it. Maybe Harry.

But Otto demanded that – even though I had an office in Beverly Hills – that for the length of the picture I stay in the office right next to him and work there. Okay! We used to go to lunch just about every day together in the commissary and every day he would order steak tartare! [laughs] and I would say to him, “How can you eat that stuff?” He says [does Preminger impression], “Deevore, you don’t know what’s good!” Couple months went by, the picture was finished. I heard him yelling at people and screaming at people, ‘cause that was what he was known for. He would yell at people in the office right next to me, then he would stick his head in and his face was still burning red, and he would say [does Preminger impression], “Deevore, was that good Preminger?” [laughs]

Wow.

SD: I says, “It was great, Otto. I’m sure they were absolutely terrified.” I mean, he used to throw Frank Sinatra off the set during The Man with the Golden Arm. He was just that kinda guy. But I got tired of bein’ there, the titles were finished, Nilsson and I had orchestrated how the lettering was gonna move, and the garbage can scene in the middle of the picture that used all those special effects of those days.

When the title design credits appear, Harry Nilsson sings: "Visual consultant and titles by Sandy Dvore and, what's more, they were executed by Pacific... ahem, how's your popcorn?"

SD: And after he did that picture, he did about four more films. I think on one picture he went back and worked with Bass. And none of ‘em made it. That broke my heart. I truly adored Otto Preminger. Last time I saw him, he came out here and called me to take him for a ride, out to the Venice Pier, he was gonna look for a location. I think he just wanted to get together and talk. And then he went back to New York. Then I got a call from his wife. Hope Bryce, a lovely lady, telling me that he’s gone. So… Skidoo, to me, was more than designing a main title. Skidoo was the memory of something marvelous.

Before you worked on Skidoo, you worked on this movie Wild in the Streets. Do you recall working on that?

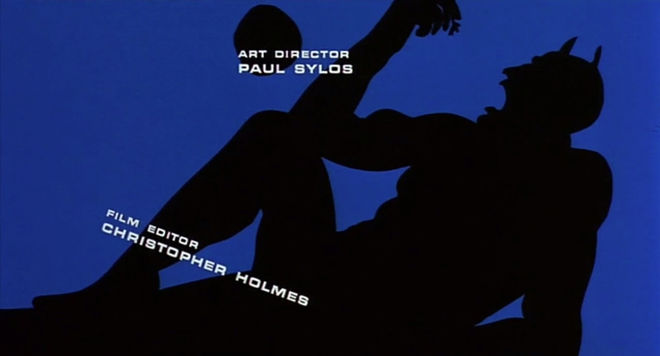

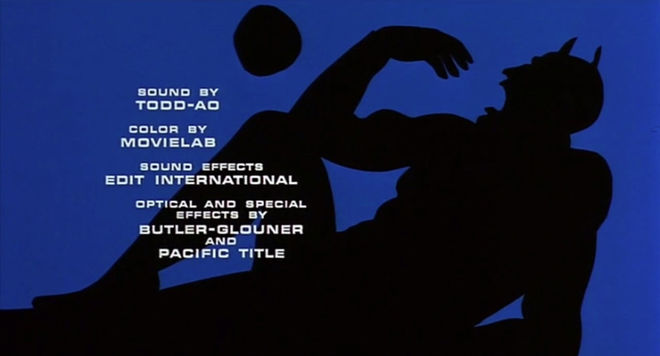

SD: It was in the ’60s. I remember that Wild in the Streets also starred that same Christopher Jones. I remember doing the lettering on Wild in the Streets.

Wild in the Streets (1968) main titles designed by Sandy Dvore

SD: By the time the early ’70s came, I was gettin' calls from AIP, Jim Nicholson, a wonderful man. He called me over to do Three in the Attic, because there was no money in town at the time and they were doing exploitation pictures for a couple hundred thousand dollars. They were doin' pictures with Roger Corman. They had this Christopher Jones, who sorta looked like James Dean, and they were trying to get him to take Dean's place, 'cause Dean was gone.

So, I got this actress over at my place and I asked her if she could just facially simulate – with her face and her eyes and her hands – a sexual climax. And I shot it as the opening titles for Three in the Attic. It had some sex to it, 'cause it was about some guy who was up in an attic with three girls and they were using him as they wished.

Three in the Attic (1968) main titles, designed by Sandy Dvore

How did you take those photos?

SD: I took those photos with my Konica. I remember shooting it in my one-bedroom apartment. I remember that I did... I was the first one with the hand reaching over and grabbing the sheet in ecstasy. I've seen that 130 times since.

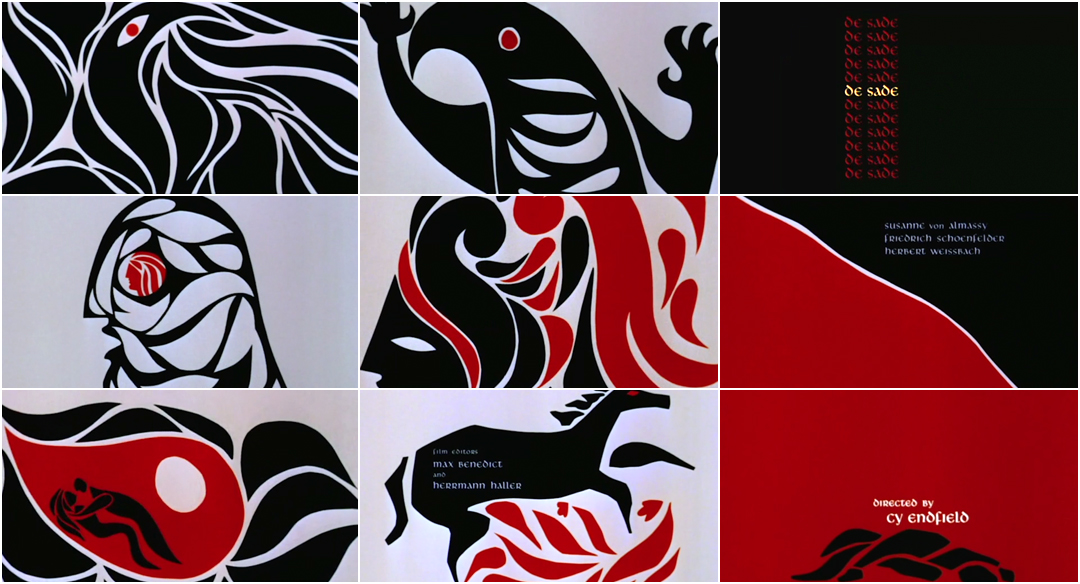

And so then they were going to do this picture De Sade. De Sade... was an idea. In 1968, I was doin' everything in red black and white. With white backgrounds. I didn't have to draw Senta Burger or Lilli Palmer. De Sade was a man whose perversions bordered on the human and the animalistic. So I figured out some acceptable way of doing that.

De Sade (1969) main title sequence, designed by Sandy Dvore

SD: When he turned into an animal, and when he played with the red ball it was like playing with life. And when he would die, he would trick everybody by coming back to life and playing with life again! Then he would get on top of a female and he would do it nicely and then the grotesque bit came in. And then he went back to playing with the red ball again. That's the way a pervert's mind works. So I tried to put that up on the big screen.

Did you work with Roger Corman at all? He was an uncredited director on this picture.

I never met Roger Corman. I did the main titles for pictures that he directed where it was my job to list his name in the credits in the proper place and so forth. He was obviously never interested in who was putting their artwork on the front of his pictures.

—Sandy DvoreThe actual main title that came a few minutes into the picture got an ovation from the audience. I'll never forget that.

Image Set: Original artwork from the main titles of De Sade (1969) by Sandy Dvore

Were you working more with the producers for these pictures? Arkoff and Nicholson?

SD: I worked with Jim Nicholson. In fact, I don't think I ever even shook hands with Sam Arkoff. But Jim Nicholson, I liked him, I always did. It may sound like a strange thing to say, but I only worked and tried to be perfect for people I liked. There were some situations where I didn't do the job because I didn't like the people. They just weren't nice, like their position gave them the right to behave badly or to talk down to people... and to me, if it turned me off, I wasn't gonna spend two-three weeks of my time knockin' myself out for somebody who made me feel bad. I was flyin’ high, I was on top of the world.

That opened for a big audience because they had Lilli Palmer and Senta Berger and Keir Dullea and they thought they had made a movie that might make it. They opened it at the Pantages to a black-tie thing, but the actual main title that came a few minutes into the picture got an ovation from the audience. I'll never forget that. I got a chill down my spine when that happened. The main title got an ovation from two thousand people!

The 1970s, AIP, and Television

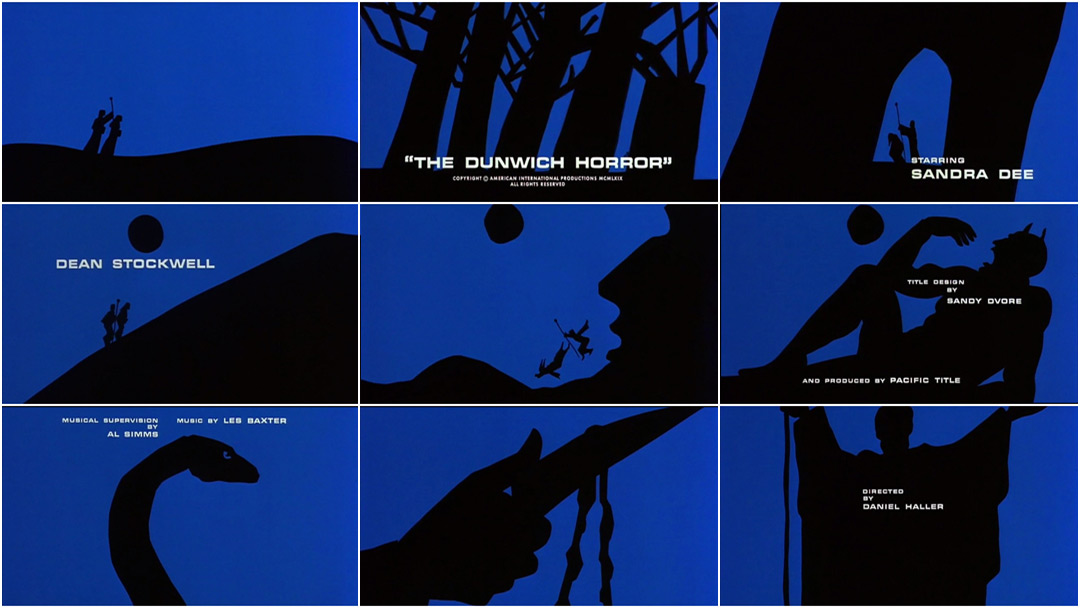

So then we get into the '70s, which started off with The Dunwich Horror, right?

SD: Yeah. The Dunwich Horror was about a girl who was pregnant with some sort of devil baby. And she was being led up the mountain to have the baby. To do the shape of the hill is one thing, but then to demonically turn that mountain into a huge devil thing who picks up the two people and devours them... well, why not?! I mean, that's the way I saw it. So that's the way I designed it.

The Dunwich Horror (1970) main title sequence, designed by Sandy Dvore

In The Dunwich Horror, credits often seem to be placed on the edges of shapes. Do you remember how or why you chose the placements?

SD: Because that’s where it looked best to me! [laughs]

Some of them seem kind of... phallic.

SD: Kind of… what?

Phallic? They look suggestive of certain body parts. Like, these credits are coming right out of the crotch…

SD: It’s been years and years since I did that main title and you’re the first person that has ever called my attention to the fact that my lettering is in the shape of a dick. [laughs]

Well, it makes sense with the story, if you consider that she’s giving birth to a devil baby!

SD: [laughs] I don’t know how I’m entirely wired subconsciously, but I don’t have any psychological thing going on with art. I have a psychological thing going on with other things in life! But art and design are the cleanest part of my psyche.

So if I want to put something on the screen that is erotic, like I did with De Sade, where the figure lays on top of the female figure, I just put them. I just pictured these things and then I did 'em.

"A film without a provocative campaign and titles is like giving a gift in a paper bag."

—Sandy Dvore. October 7, 1971, Albert Lea Evening Tribune/AP

SD: A little later, I got a call from Columbia. And I had a meeting with a man named Paul Junger Witt. He was at Columbia Television or Columbia Production at the time. This Paul Witt told me that they had a series about a mother and her kids forming a band, playing rock ‘n roll. I said, “Well, who's in it?” He says Shirley Jones.

Shirley Jones was a big musical movie star. And at that time, it was considered a comedown for a big movie star to do television. The screen was smaller! Nobody came out here to be on the small screen, you came out here to be on the big screen and have people stuffing popcorn into their mouth, have Cinemascope and surround sound! [laughs] I said, “What's the name of the show?” He said, “It's called Partridge Family.”

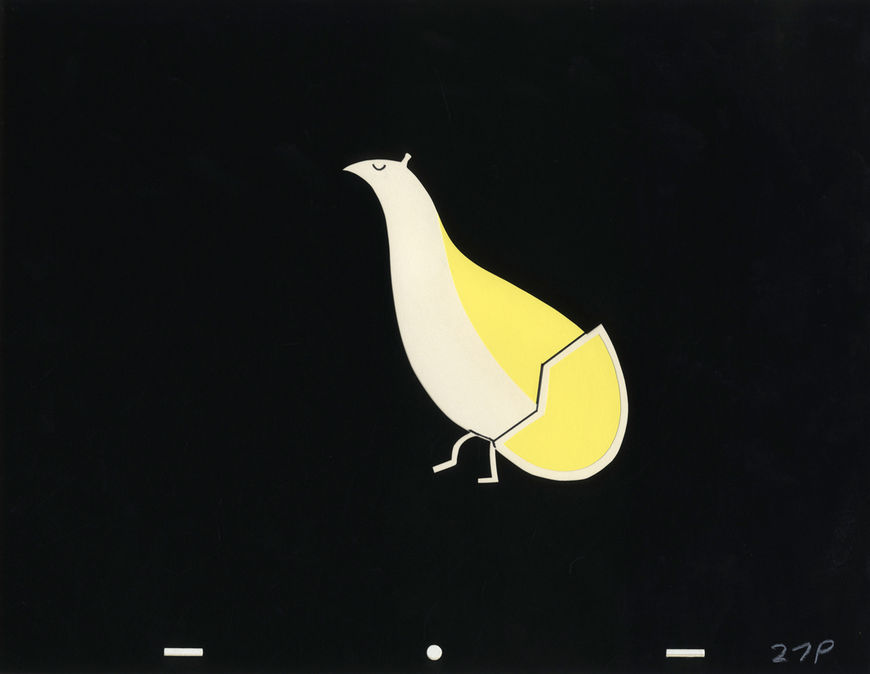

Stills from The Partridge Family (1970) main titles, designed by Sandy Dvore

The Partridge Family (1970) main title sequence, designed by Sandy Dvore

SD: I couldn't believe it was gonna be that easy. But I really did a good performance. He was sitting back in a lean-back chair. And the front of his desk had this ornamental piece of wood that looked like little stairs... you know, it was a classic desk. So, I remember, I put my head down like this – into my chest – and I closed my eyes tight as if I was doing some great creative searching.

Well, back in Illinois, I had a good old shotgun and I used to go out into the fields and do some pheasant huntin'. I loved goin' through the frost and dreamin', feelin' the breeze blowin'. I loved pheasant huntin'. So I knew what a partridge looked like – they were just smaller, and they had a little crown on their head. They were in between a pheasant and a quail, as far as what they looked like. And I made believe that I was going for something great. I think I put my head down so I wouldn't burst out laughing! And he sat there looking at me. And I says, “I know what I'll do!” And he says, “What?”

And that thing on the end of his desk, that little stairway, I ran my fingers across it, walked these two fingers across, and I says, “I'll do a family of partridges.” [walks fingers across table] And he stopped, he leaned back in his chair, looked up at the ceiling, and he said, with his hands up like this [raises hands], he said, “They said you were fuckin' great!”

Original animation cel from The Partridge Family main titles

Artwork for The Partridge Family title sequence by Sandy Dvore

SD: And I thought to myself, “Please god, don't let this be a mistake. Let this just keep happening.” And it did!

The next thing I got called in for after The Partridge Family, I was sittin' on the floor designing The Waltons, for Lee Rich, who had come from Leo Burnett as a big muckymuck and now he wanted to be a producer in Hollywood. And I got called in to do an opening for this The Waltons.

The Waltons title sequence illustrations by Sandy Dvore

SD: When I was growin' up, mountain people from the Smoky Mountains, I read in my book, they were so poor, coal miners' kids, that they would make their clothes out of potato sacks. The mothers would cut 'em out of potato sacks. So I got this screen and we designed this screen that simulated canvas potato sack material and I tried my best to match the colour.

The Waltons (1973) season 7 main title sequence, designed by Sandy Dvore

So that's where that brown comes from.

SD: That was the opening title and it does look like the colour of a potato sack! And when it was on television you could see the grain. So that became The Waltons.

But the first experience with actually doin' something that went big was The Partridge Family. That’s where I met Chuck McKimson and his brother Bob.

They were working at Pacific Title at the time?

They were animators in the days of Fantasia, Snow White, and they were like... Chuck McKimson was just great. And he liked me so much and I liked him so much. He would sit at his desk on the second floor of Pacific Title and I would bring a storyboard – a pad with each frame with the drawings in it, you know, of how the thing was supposed to go and he would make the count sheet. The amount of seconds and everything so that everything actually came out in 30 seconds or one minute or whatever the main title was supposed to be. And we had one very special timing device that isn't used today in animation, our timing device was ... how long do you want this title, how long do you want this dissolve to be when the mother turns her head and looks back at the partridges? How long should that turn be? Turn should be [tap-tap-taps on the table] everything was timed with the tap of a pencil or the turn of a head. And everything came out perfect! It never missed. We did this for years.

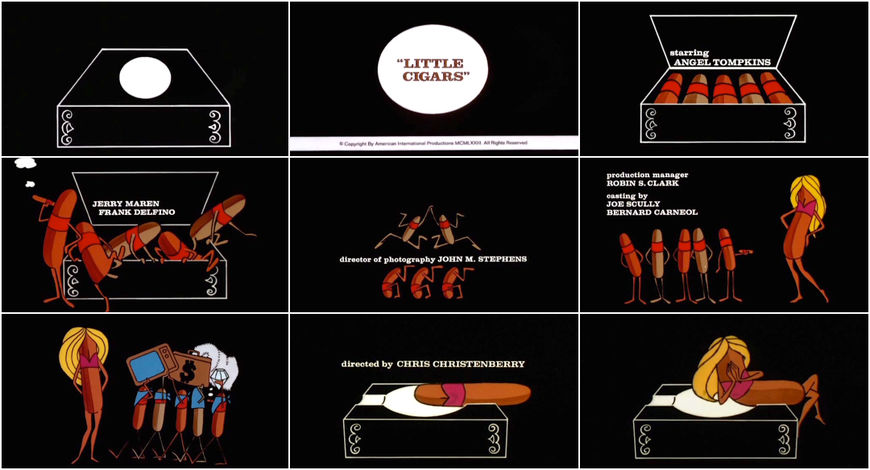

And then I did a trade ad for American International Pictures and they didn't have a logo except for the lettering, so I did that round circle with the American capital. So they got a logo for a trade ad. It's used on every movie. It's used in Little Cigars — on top of the cigar box was their logo.

Still from the beginning of the Little Cigars title sequence featuring the AIP logo (also designed by Sandy Dvore)

Little Cigars (1973) main title sequence, designed by Sandy Dvore

SD: So I did a lot of things and then they wanted to put somethin' special on this black vampire picture. Jim Nicholson called me in and said, “We’re doing a vampire movie.” Vampire movies were starting to do business then. But it’s about a black vampire. Blacula. I did Blacula. And I had the bat having sex with a drop of blood and it would turn into a woman and then he would absorb it by humping it and then it would turn into a drop of blood again and he'd chase it around.

Blacula (1972) main title sequence, designed by Sandy Dvore

How did you actually make that? It looks like a lot of close-ups on paper.

SD: That's all animation, cels – hundreds of cels. I had some packaging that had that grey marbled textured background – we had big rolls of paper. I used that as a background, then I found areas where the guy with the big collar, who could turn into a bat, could jump around and chase the drop of blood. And then I found areas where the drop of blood could turn into the woman and lay down. And then I found little areas that – where the guy, having changed into a bat, could go through and down and get on top of her. It was all very, very simple to me.

Who did you work with to animate it?

SD: That was one time when Chuck McKimson couldn’t do it. So he asked me to work with his brother Bob McKimson. So Bob McKimson actually animated from my storyboard.

Scream Blacula Scream (1973) main title sequence, designed by Sandy Dvore

But none of these ideas were like, what will I do next? Or what should come next? It was just – I could see it all finished before I started. When I would get a telephone call for a trade ad – for Dean Jones or for Barbara Eden or for the Smothers Brothers – the only work was in the execution. I always had the complete idea and saw it before I put the phone down.

Would they show you the film, and you’d get some ideas from that?

SD: No. Because… it’s like some guy in the business once said to my friend Allen Epstein – who was a television producer, Green/Epstein Productions, he and I used to fish together – he said, “Oh yeah, that’s the guy who puts his artwork on other people’s pictures.” I never forgot that. I always wondered if it was an insult or just an observation.

Did you meet the director, William Crain, for Blacula? Did he have any input?

SD: Not at all. Nobody had any input on anything I did. The only time I was ever asked to do anybody a favour is when Frank Sinatra requested if I could just fit a little orange in… He would never tell anybody but if I could just find a way to fit a little orange...

The colour?

SD: Yeah. The colour orange. That was his lucky colour. And so I obliged him because I had no reason not to.

Later I did a thing called Sable, which was a replacement show...

Sable (1987) main titles, designed by Sandy Dvore

In Sable and in Blacula, The McMasters, De Sade, Dunwich Horror, you use an abstract shape sort of style. Previously you'd done a lot of portrait illustrations, and with these it seems like you went in a new direction. What was the origin of that?

SD: [laughs] I don't know... When I had my thing at the Paley, my exhibit, I was talking to one of the curators and I mentioned the fact that I liked having the reputation of being the guy who came up with somethin' new. The guy who did “new.” And we used that as the catch phrase for the whole exhibit.

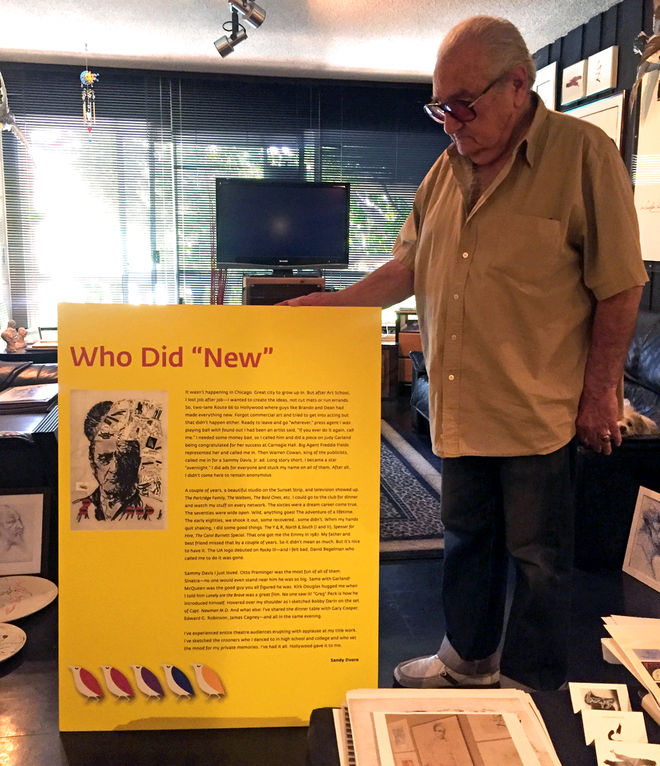

Sandy Dvore, the man who did "new", with the placard from his 2010 exhibit at the Paley Center

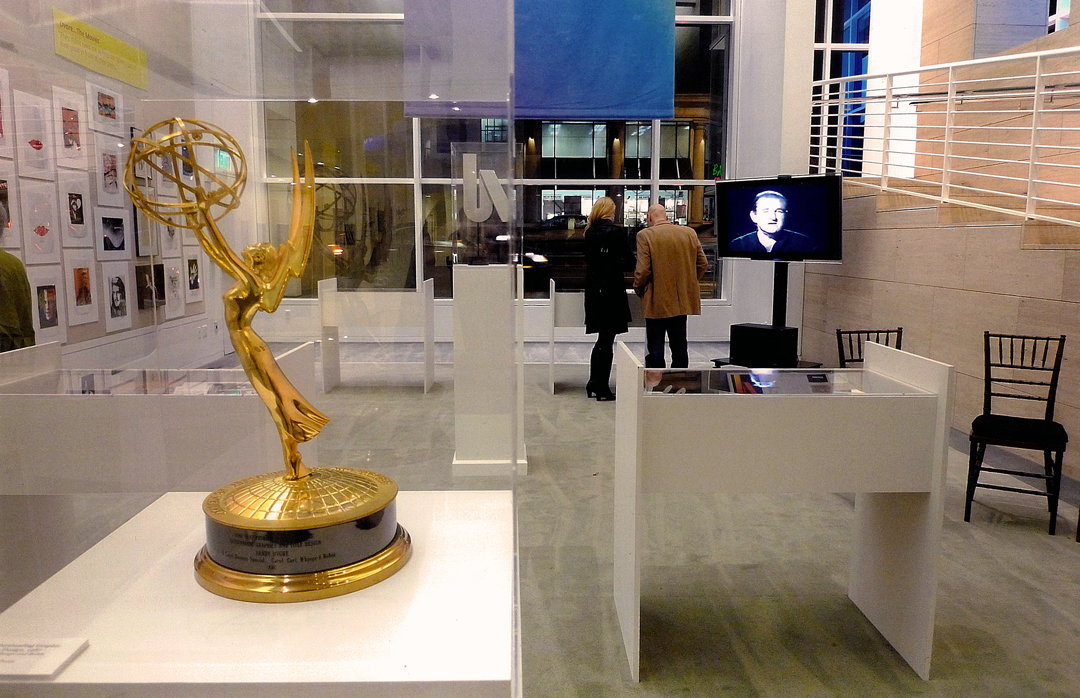

Sandy Dvore's exhibit at The Paley Center, 2010-2011

SD: But the main reason I liked finding all these new techniques and experiments and images and ways of doing this was because I wanted to put on a show. It started from the trade ads... I would do a drawing one day. Then I would do a design. Then I would do a watercolour combination. And if you're good at one thing, like illustrations, it's a fickle town. These are fickle people, creatively. I wanted to keep them guessing as to what I was gonna do next. I was havin' a good time. It was simple as all that.

The McMasters (1970) main titles, designed by Sandy Dvore

SD: But as far as getting the ideas… the one thing I never wanted was to see one of my things and then to have people know that the next thing they saw was mine. Some of the greatest designers – or named the greatest – if you saw one thing they did, you saw 'em all.

Yeah, they had a signature.

SD: And the designer that’s considered the best of 'em all, if you saw one of his titles, you absolutely saw 'em all. But I didn't go for that. I don’t have any clever reasons for the ideas that I get.

It’s much more instinctual?

SD: The scenes just come to me. I just see them and I happen to have been in a marvellous position of people letting me do anything that I wanted. I did the same thing that brought me out here, but when I did it back there [in Chicago], they fired me. Here, they gave me Emmys for it.

You found your spot.

SD: Thank God, because if I hadn’t, it’s like my kid sister once said, “You woulda been on Skid Row.” I don’t know how to do anything else! I mean, it was a miracle career that happened from nowhere.

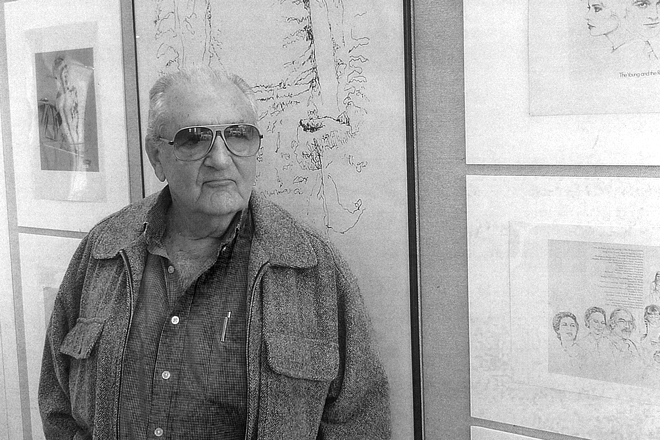

Sandy Dvore at his exhibit at the Paley Center, 2010