If you were thrust into the middle of a multi-faction uprising against an oppressive regime, what would you do? How would you know which side to choose? How would your friends and family affect that decision? Those are a few of the questions posed by 1979 Revolution: Black Friday, an ambitious new interactive experience from studio iNK Stories, a team of filmmakers and game developers whose past work includes the Grand Theft Auto series.

Blending together adventure game mechanics with film-style narrative and documentary storytelling, 1979 Revolution is described by its creators as a “vérité game”. The action takes place during the real-life events of the Iranian Revolution and puts players in the role of Reza Shirazi (Bobby Naderi), a young photojournalist who has recently returned home and finds himself caught in the middle of the tumultuous political struggle.

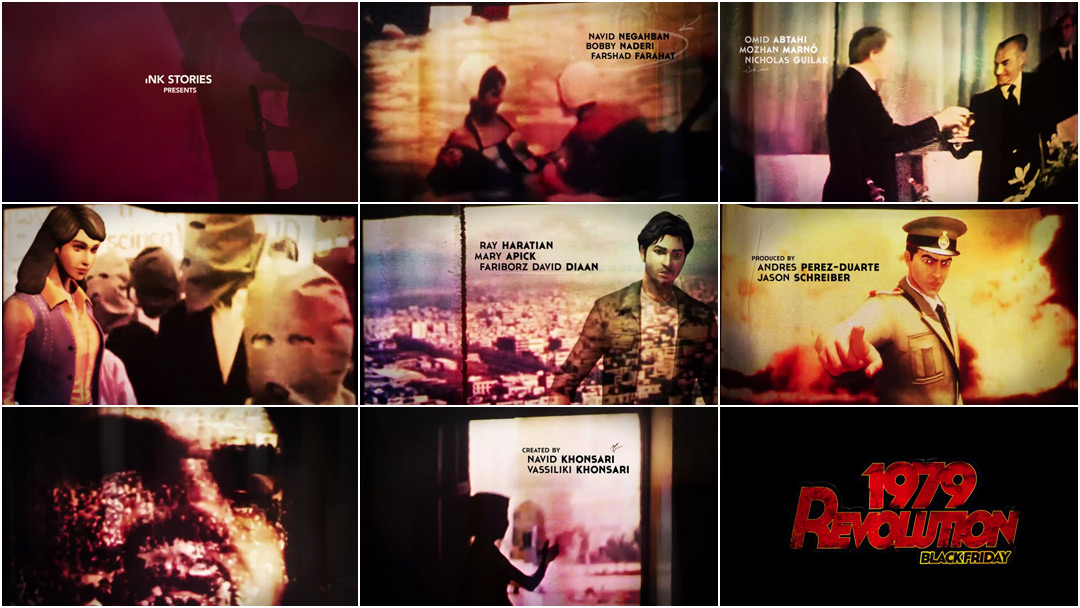

Despite 1979 Revolution’s interactive nature – or perhaps because of it – the iNK Stories team chose to return to their filmmaking roots for the game’s opening. Set to the melancholy ballad “Mara Beboos” (“Kiss Me - One last time”), a movie-inspired title sequence provides a fitting entry point for players. Mixing archival footage, personal home movies, and motion captured in-game performances, the titles create a window into pre-revolutionary Iran, as well as hint at the future of the country and its people. The nation glimpsed in the opening is where the game’s action begins. It’s an Iran rarely seen today – one full of hope and possibility for a time – an Iran largely erased by the Ayatollah and his regime.

1979 Revolution: Black Friday is now banned in Iran and is labelled as propaganda designed to “damage [the] spirits” of Iranian youth. Many of the developers chose to work under aliases to protect their identities. Director Navid Khonsari was accused of espionage in his home country and he and his family are unlikely to be able to return as a result, while one of the game’s concept artists, Mr. Phoenix, eventually fled Iran due his work on the game. It’s a chilling reminder that creating art – even video games – can still come at great personal cost to its creators.

A discussion with Director NAVID KHONSARI and Creative Directors ANDRES PEREZ-DUARTE and VASSILIKI “BESSIE” KHONSARI.

So tell us a bit about yourselves and how your company, iNK Stories, came to be.

Navid: Ink Stories started in 2006 after my departure from Rockstar Games. I was there for six years as the cinematic director and head of production. I left to pursue film and did two feature documentaries under the iNK Stories banner. That’s how I met Bessie. She had done a number of feature documentaries as a visual anthropologist and a cinematographer, so it became a perfect combination.

With my background in gaming, iNK Stories also went on to facilitate other games like Alan Wake and Homefront, in terms of us helping them with casting and cinematics – the entire cinematic pipeline.

Alan Wake (2010) main titles

Navid: In the past 10 years we’ve gone on to make documentaries, video games, graphic novels, and are venturing now into narrative feature films. Now after three-and-a-half years of financing and production we released 1979 Revolution to the world via Steam.

That’s a really exciting mix of projects. It’s interesting that you mention having a film background because 1979 Revolution is not a video game in the way many might think. It has some similarities to Telltale’s Walking Dead adventure games, but it’s very filmic. Was that the original vision?

Navid: Absolutely! It’s an adventure game, but it’s an adventure game based on real events and real people’s experiences. And because it’s an adventure game it allows people to have their own narrative. As a result it’s quite complementary to convey that through some of the great production means that we have out there, such as motion capture, which lets us use real cinematography to communicate what’s happening on stage with the characters. So it’s an adventure game based on real events, but using the classic tools and methods of film to convey a cinematic story.

Image set: 1979 Revolution: Black Friday motion capture behind the scenes photos

Navid, you grew up in pre-revolutionary Iran, right? What was the impetus for you to make 1979 Revolution and why make it now?

Navid: It’s really simple: When the team first discussed the idea of a hybrid between a documentary and an interactive experience, we looked at the market to see who was doing that so we could kind of follow their lead but we didn’t see anyone. In fact, when we looked across the entirety of gaming history there have been very, very few examples – and certainly none that have been commercially successful – of games based on real events. That got us excited. We saw the possibility of not just a game but a new genre.

So then we started thinking about the story we wanted to tell. Based on my background in gaming I saw a revolution as an incredible environment, an incredible bed to question morality, to really give players hard choices as they navigate not only physically through streets but also emotionally through moral choices. The 1979 Iranian Revolution seemed like the perfect fit, but for us to be successful and for us to get the respect of audiences, we knew we had to put ourselves into the experience we were creating. It had to be personal, people had to connect with it in order to understand it was real. If the authorship was coming from someone who was telling their real story – and on top of that the 40 people that we interviewed – then we’re putting more on the line. That would be the only way to legitimize this genre.

We saw the possibility of not just a game but a new genre.

1979 Revolution: Black Friday trailer

Navid: And not that I want to jump ahead, but obviously the opening titles really show all the elements we’ve discussed in a very short period. Images of the real world, images of the personal, images of the game, and also images of the historical implications of what took place during the summer of 1978 and the year of 1979.

So at what point in the game’s development was it decided to have a title sequence? How did you talk about that?

Navid: We always knew we were going to do an opening sequence because we were embracing the entire cinematic package of what we were creating – that hybrid of narrative film, real-world documentary, and interactive game. But we only had very general ideas until we sat down to hash out the idea.

Visual inspirations for the 1979 Revolution title sequence

Vassiliki: We had some real challenges ahead of us because we wanted to use this very personal archival footage but we didn’t want it to feel like a newsreel. We didn’t want to convey this accountant’s version of history through archival footage, and by the same token, when you have real archival footage and you’re trying to mix it with video game Maya files it looks very campy. We had to find a balance between the two.

Andres: One of the biggest challenges was to merge those elements and find a balance between what looks tasteful, what sets up the history, and what prepares the player for the adventure. We wanted to make sure that we were setting up the mode and the emotions that people were going to see later on in the game. A lot of the assets you see in the title sequence you are able to explore in the later scenes.

Navid: Unlike a lot of other elements of the game, the opening titles probably went through more iterations than anything else. We scrapped more things and started from the ground up more than anything else…

What were the original concepts? How did you develop the sequence?

Andres: There were several concepts originally. Since the main character is a photojournalist, one of our early concepts was to use the development of pictures – the pictures you were going to develop throughout the game – and the water as a mechanism to bring on the titles.

Photo development concept video

Andres: The only problem with that was that it didn’t feel as interactive as we wanted it to be. We kept going back and forth with that because the player is going to be able to discover the pictures later on in the game, so we wanted to keep that element of surprise. The home movie footage that we used in the title sequence, on the other hand, was just these little snippets. We thought it was a nice way to hint at these little moments.

Another concept we talked about had all these molotov cocktails with fire emerging from the streets with the revolt and the protests. We started discussing ways to make it interactive, and there was definitely talk about the player being able to interact with the world and discover the titles. Again, it started to feel like it might be distracting. This was the one opportunity we had to really make the audience sit back and just watch while they prep for the game.

Navid: There were also a couple of things which we kind of limited ourselves to. We recognized that this was a game and that there would be pushback if we went too live-action with it. From my experience with other games, there’s always a negative opinion when you see a trailer that looks super slick and then none of those elements are actually in the game. We really wanted to include assets from within the game to make sure that it was a tight piece from beginning to end, relating to all the key elements within the game and experience.

We really wanted to include assets from within the game to make sure that it was a tight piece from beginning to end.

Image set: 1979 Revolution: Black Friday in-game screenshots

Vassiliki: We knew that there was this sweet spot that we were fishing for. We wanted the opening title sequence to evoke more of an ethereal impression than a literal backstory to the revolution. But we felt like we needed to also set the tone for people who don’t know anything about Iran or anything about the revolution, so that they can feel like they’re in a comfortable headspace when they’re starting the game. We had to kill our own darlings sometimes, sacrifice them for the greater good.

Did you work with any motion designers on this?

Vassiliki: We hired so many different motion designers and it was really disappointing. We felt like we were very clear at conveying what we saw but it wasn’t working. We were hoping someone would come and bring what we wanted to see and then bring more, but that just wasn’t happening. At some point we decided that someone had cast an evil eye on us! [laughs] It just felt like everything was going sideways. We’d taken every absolute approach that we could from our own respective professional schools. We were going to make these lists, screengrab references, and make a very specific moodbook and all this stuff…

Andres: At one point we were working with this particular artist – Navid and Bessie were at Sundance – and we wrote three or four pages of notes of exactly what had to happen at which second. We are very meticulous when it comes to visuals, and it was very hard to convey some of this stuff no matter what kind of directions we were giving. It was just not up to par for what we wanted. It also started creating another conversation among the three of us: “Do we need to go a different direction with this?” There were maybe 15 different versions of the one you’re seeing in the final game, many with the same footage just arranged differently.

1979 Revolution: Black Friday main title rough cut

Vassiliki: It’s almost like we had to go to the heart of darkness and then out the other side. We had been defeated so many times by not seeing something that resonated with us that we just started playing. “Screw it, let’s just project some of this footage on the wall and see what that looks like!” The idea of projection resonated with us. The layers, the projection of the video game into history, conceptually is very relevant to the game. So we started playing with these concepts and departed from overthinking stuff. That’s how we started to find a direction that we were all really excited about.

Obviously you three were also working to develop an entire game at the same time, right? How did you balance all that?

Andres: That’s a great question. There’s eight of us and we all have to be jumping in and out. We started designing the title sequence in September 2015 and it was not completed until the last week of March 2016.

We were also doing all the UI design for the game in-house, so we had to be jumping back and forth. At one point we said “Maybe we don’t do a title sequence?” We considered scrapping the title sequence completely. But again, it was like this is our baby and we really wanted to have it.

Navid: We weren’t going to scrap it! We were just frustrated.

Vassiliki: [laughs] It really spoke to our inner filmmaker. As filmmakers at heart title sequences have always been very inspiring, so we wanted to put our best foot forward.

Andres: And there’s this website, Art of the Title, which kept popping up! [laughs] We kept going back and forth looking for references, like, “Have you seen this sequence?” “Have you seen that one?” We have to do this!

So what were the steps in the production process? Did you storyboard?

Andres: The very first step was choosing the footage. That was the hardest thing. We had over 30 hours of footage. We were determined to use all the footage of Navid’s family that you see in the game, but there was so much other footage that we wanted to use – archival footage, newsreels, and stuff like that. So we started by picking out these little instances from documentaries or stuff that was available, and laying it down in the timeline and saying we’re not going to go past one minute thirty seconds.

Vassiliki: We had a shopping list for that footage, in terms of what we needed to convey for the story. We needed some personal shots, we needed to have women in it, we needed to have hints of the violence erupting, we needed domestic scenes inside of homes. For Navid it was also very important to show happy family moments, to not just focus on the violence or the hardship, but to show that this is a rich culture of family and happiness within that family.

It was also very important to show happy family moments, to not just focus on the violence or the hardship.

Still frame from the home movie that opens the title sequence

Andres: We actually did not storyboard it with styleframes the way you’ve probably seen. We did some styleframes for the way it was going to be laid out, but in terms of storyboards it was actually just a rough cut that we used as a bible. Bess would be doing the editing, I would be doing the compositing in After Effects, and then we would have to go in – After Effects is horrible with editing – and try to move things around, it would get all mixed up and then we’d have to go back to the timeline and fix it.

The first shot was the hardest thing because we wanted to have a very strong shot to start with. We originally had one with the shoppers and the coronation and stuff, then we had another one too, but we ended up using the one at the beach with Navid’s mom at the beach. It’s such a strong statement right now about what’s going on in Iran since women have to wear the chādor and they aren’t allowed to show any skin. So this was kind of our opening statement. It’s the shot that really carries out the feel and mood of the piece.

A chādor or chādar is an outer garment or open cloak worn by many Iranian women in public spaces or outdoors.

There’s a particular shot – the shot of the modern dressed woman quickly flashing into the chādor covering – that really stuck with me.

Navid: That’s the last shot towards the end of the sequence –that was something Andres really spearheaded in order for us to show the duality. It was our way to hint at the trajectory of the revolution. Then to follow that up with the shot of the airplane leaving – the journey of so many Iranians who fled the country – those two shots back-to-back is our way of hinting at the changes that were coming to Iran, to the society, that these changes would cause a huge drain of Iranian citizens as they went in search of a calm, more sustainable life.

Navid: That woman happens to be my cousin. She was somebody who’d gone to Berkeley, was educated and lived in California for some time, and would go back and forth between Iran and California. She reflects a huge movement of Iranian students who were abroad who came back for the revolution hoping to create some kind of change. Then as the regime changed going from being heroes of the revolution to sought-after revolutionary leaders going against the new establishment. That’s also the trajectory of a number of people of that generation who came back.

Was there anything that took you by surprise when working on this sequence?

Andres: What really caught me by surprise was how we were able to accentuate the transitions. Originally we were so married to cumbersome transitions, but when we dropped them the title actually started breathing. That’s when we realized we didn’t need all of this! We’d spent so much time trying to figure out how to make these transitions work that we were almost at war with each other. It was a breath of fresh air.

Navid: For me it was the final pass when Bessie started putting in audio bits that it really started to resonate with me. The sound of a child – that’s actually our daughter – and that song, an iteration of a classic song from the 1940s in Iran called “Mara Beboos”. It means “Kiss Me” and it’s a song supposedly sung by an imprisoned father who’s about to be executed. He’s tells his daughter “Kiss me, kiss me for the last time because you’re not going to see me again.”

Early projection test

The combination of the emotional impact of our iteration of that song and then the sound design, bringing in lines from within the game and also some of the interviews we did. That was the icing on the cake, taking those images and not only make them feel personal, but also seem real. That’s what caught me off guard. Thanks to Bessie and our composer Nima it really allowed what we’d created visually to step up to that next level.

Vassiliki: Once we put in the finishing touches of the audio it passed our test. Are you getting chills or not? If you’re getting chills, it’s good. We all put our headphones on and got chills. We did it. We’re very, very happy with it.

For me what was most surprising – both disheartening and encouraging at times – was the overall creative process. No matter how many times you go through it you always feel like “OK, I should have a better sense of this going into it this time.” We had hammered out so many creative decisions that we were almost in this fatigued headspace. We were putting in the effort, putting in the time, putting in the thought, putting in the creativity, but it just wasn’t getting there. You have to bark up many different trees, you have to keep pushing on and eventually it will show itself. It was a reminder that this is not a linear process. You may feel like you’re almost there and then you’re going to take twelve steps back. You have to go there. You can’t just say “Fuck it, I’m going to commit to this shitty idea.” And we didn’t because we’re all obsessive compulsive and continued to push on. It was continually surprising just how harry the creative process can be, but also that you just need to stick with it and you will ultimately be rewarded.

Do you feel like more games should use title sequences to help establish tone and setting? Or do you feel that it’s more of a case by case thing and very specific to your game?

Navid: It would be unfair to say that title sequences aren’t being utilized by games. A lot of the games I’ve worked on we always paid attention to the opening. If you take a look at the Grand Theft Auto III opening titles, that was a huge element of the branding that worked hand in hand with the game. If you look at the opening titles of Alan Wake, which I worked with the Remedy guys on, they did a phenomenal job. There are folks within our own realm, like Telltale, who also recognize the importance of the opening titles – definitely with Wolf Among Us and its use of the comic book aesthetic and the colours.

You have a responsibility as a creator to initiate or start the spark of the narrative with something that’s going to establish mood, tone, and theme.

The Wolf Among Us (2013) main titles, designed by Telltale

Navid: If you’re going to do a game, whether it’s a first person shooter or a side scroller, if it’s embracing some kind of narrative then you have a responsibility as a creator to initiate or start the spark of the narrative with something that’s going to establish mood, tone, and theme – and nothing does a better job of that than opening titles.

For us it’s a key part of bringing people into the experience. We’re not just creating a game for gamers. For non-gamers, the ability for them to be able to draw similarities to film, to TV, to documentary, to things that they’re familiar with, is going to help them transition into the experience rather than feeling standoffish because they don’t consider themselves a gamer. It’s a great vehicle to embrace a larger audience to say that what we’re creating here is a story – a story that you can experience and that is not about hand eye coordination.

It all comes together very well. OK, so I’d like to ask each of you about your personal favourite title sequences. What are some of your favourites?

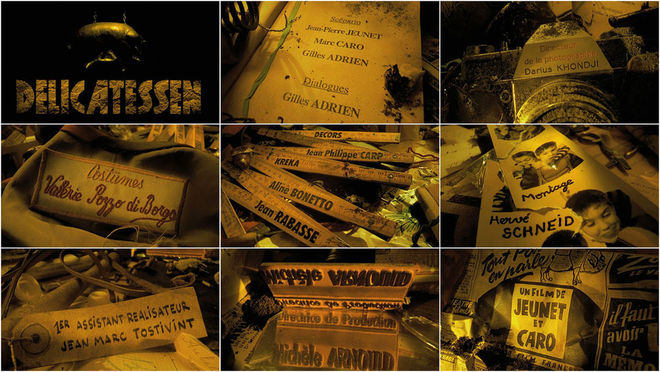

Andres: Oh god! This is a tough one. Let me go to the site! [laughs] I would have to say that Delicatessen is one of my favourites.

Delicatessen (1991) main titles, designed by Marc Bruckert

Vassiliki: In terms of stuff that I’ve been watching lately, Melancholia and Lars von Trier is an ongoing inspiration for me. Melancholia is sort of a departure from the formula of opening titles in that it’s so excessive and so big, but also so glorious.

Navid: I definitely have some favourites. Do the Right Thing with Rosie Perez. It was so simple, but just the power of it. It established the tone of the movie and legitimized the direction that Spike Lee took with the story that he was telling. It was extremely powerful.

Do the Right Thing (1989) main titles, designed by Balsmeyer & Everett, Inc.

Great picks! So is there anything that you’ve seen or watched or played lately that’s been particularly exciting to you?

Andres: In terms of games, I’ve started playing Her Story and Life is Strange, which are both really big right now. The whole genre of Her Story is just so left field and at the same time it’s just such a great indie representation and a fun ride.

Navid: There’s this Iranian movie that just came out on Netflix that we happened to come across called Taxi by Jafar Panahi. He’s a writer/director who’s done extremely well critically and at festivals like Cannes and Venice, but he was arrested and he’s been banned from making movies. It’s just a camera up on a dashboard in a taxi and he’s having these conversations. He puts himself in front of the camera rather than hiding behind it. It’s a great approach, especially with the limitations that were put on him.

Game-wise I definitely think Quantum Break by Remedy is just as cinematic as you get. It’s really, really well done. What I’m also waiting for is Uncharted 4: A Thief’s End. I’ve been a big fan of that franchise.

Vassiliki: As far as recent inspiration movies we have been watching a lot of Iranian flicks lately. A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night in one. It’s got a very strong artistic vision, and the content and the story aren’t compromised by this artistic vision. It just adds to it! That was really inspiring to see a movie that can do both of those things.

A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (2014) main titles, designed by Logan

Vassiliki: At Sundance this year we saw Babak Anvari’s Under the Shadow. He’s such a talented director. Actually one of the leads in that film, Bobby Naderi, is one of the leads in our game. We know a lot of the crew and they’re such a talented group of actors and filmmakers. But it’s sort of this funny Iranian parallel to The Shining. It’s such a refreshing movie because it takes something that’s as dark and politically charged as the Iran-Iraq War and compartmentalizes it in this other part of your brain within the horror genre. It really allows you to engage with it in a different and fresh way.