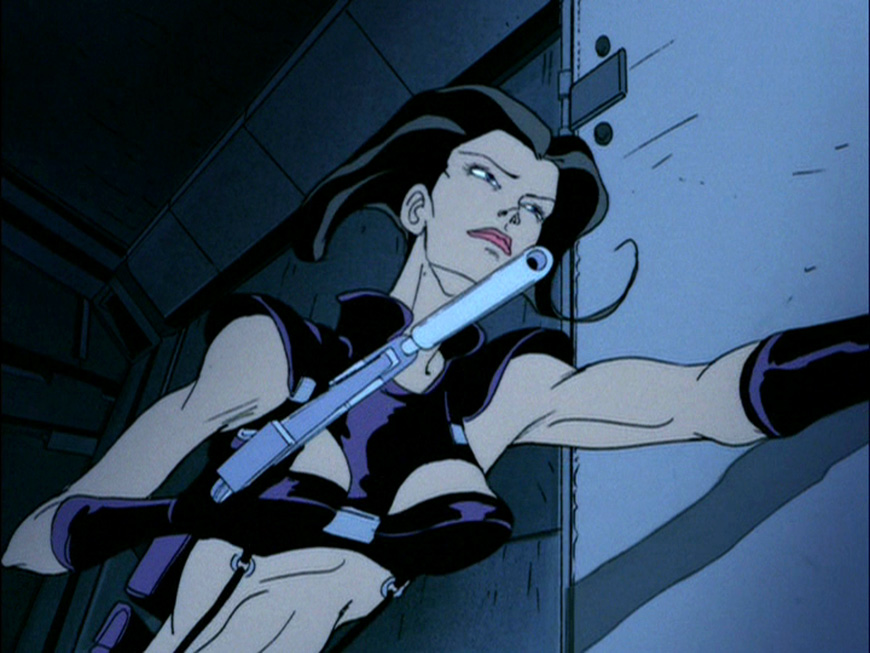

The French philosopher Michel Foucault once wrote, “The gaze that sees is the gaze that dominates.” Though originally intended to describe the biological reductionist philosophy of modern medicine, this phrase could easily serve as the maxim of Æon Flux. Combining the far and varied influences of New Wave cinema, artistic expressionism, Franco-Belgian comics, and spiritual gnosticism, the 1991 avant-garde animated series follows the exploits of a mysterious dominatrix-cum-agent saboteur and her authoritarian nemesis/lover Trevor Goodchild – two opposing forces clashing as the pretenses of morality and justice are left morphed and unrecognizable in their wake.

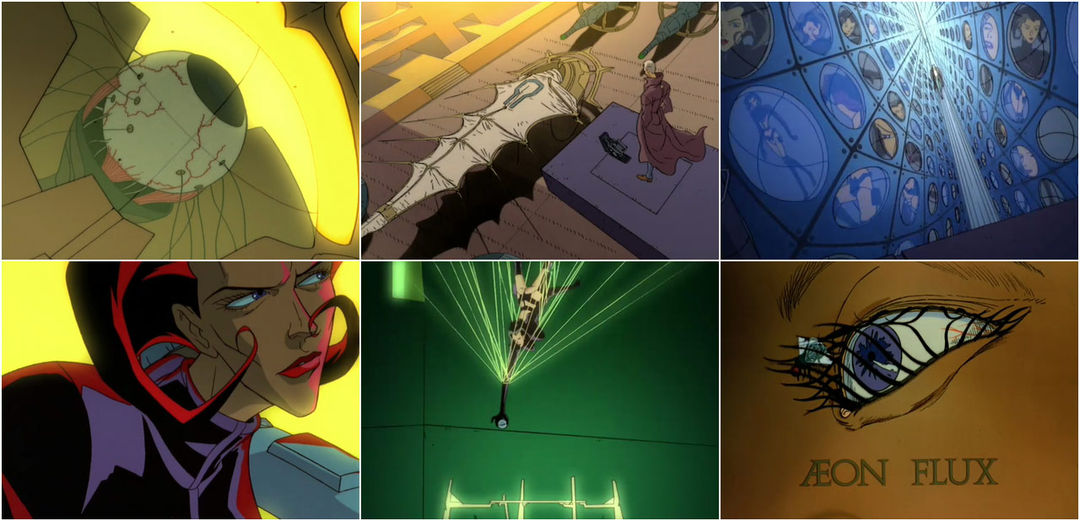

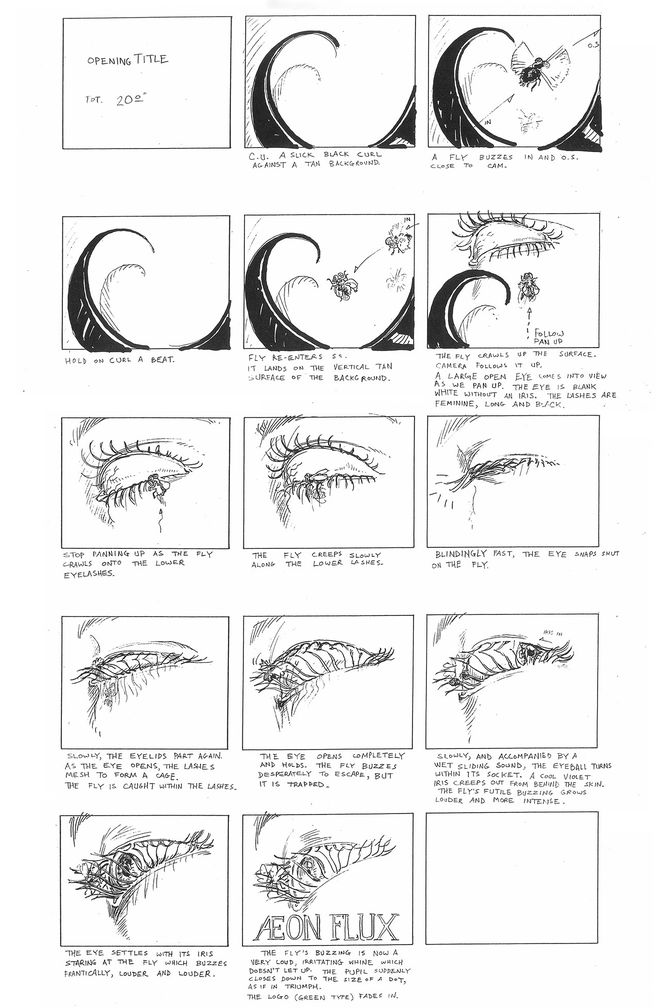

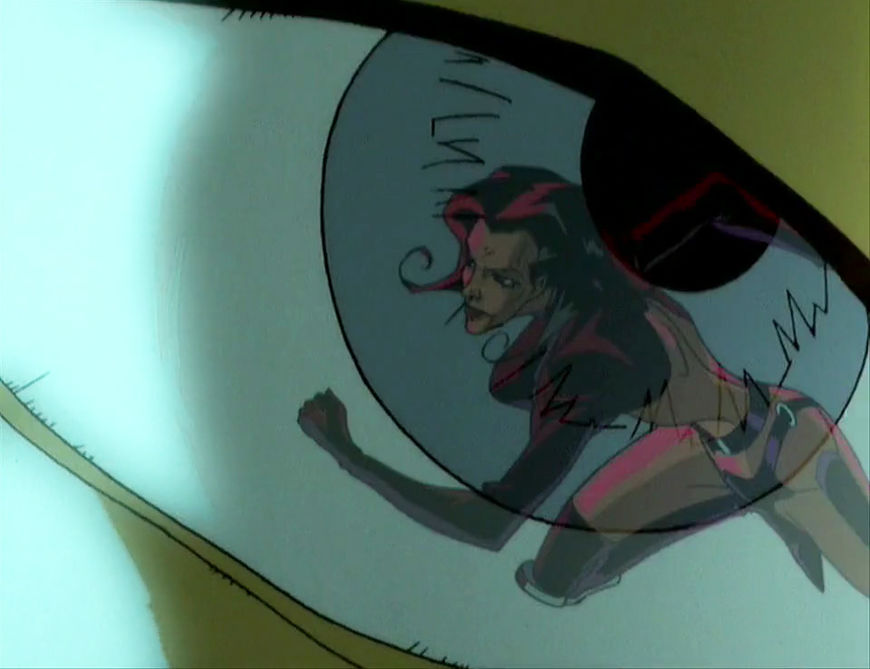

When animator Peter Chung was first approached by Colossal Pictures' Japhet Asher in the early nineties to direct a series of shorts for MTV’s experimental animation block Liquid Television, Chung seized the opportunity to break out of the mold of his previous work on such shows as Transformers and Klasky Csupo’s Rugrats and create a series that was all its own. Spanning six animated shorts and ten half-hour episodes, Chung’s magnum opus eschewed convention and defied the trite assumptions of what was possible to achieve through network animation. Far from being simply enthralling on a visual level, Æon Flux was at once a shrewd deconstruction of Hollywood sensationalism and a savvy examination of the power inherent in the act of both seeing and being seen. Nowhere is this more succinctly exemplified than in the series’ opening title sequence; an errant fly, skittering along the rim of an unconscious eye, only to be trapped in the folds of lashes. The muscles of the iris part, rolling forward and tightening in focus of its prey. Punctuated by a discordant sting, this image is the essence of Æon Flux made literal: an unflinching force of violence and seduction, manifest in an entity whose true motives are all but alien and inscrutable to the audience.

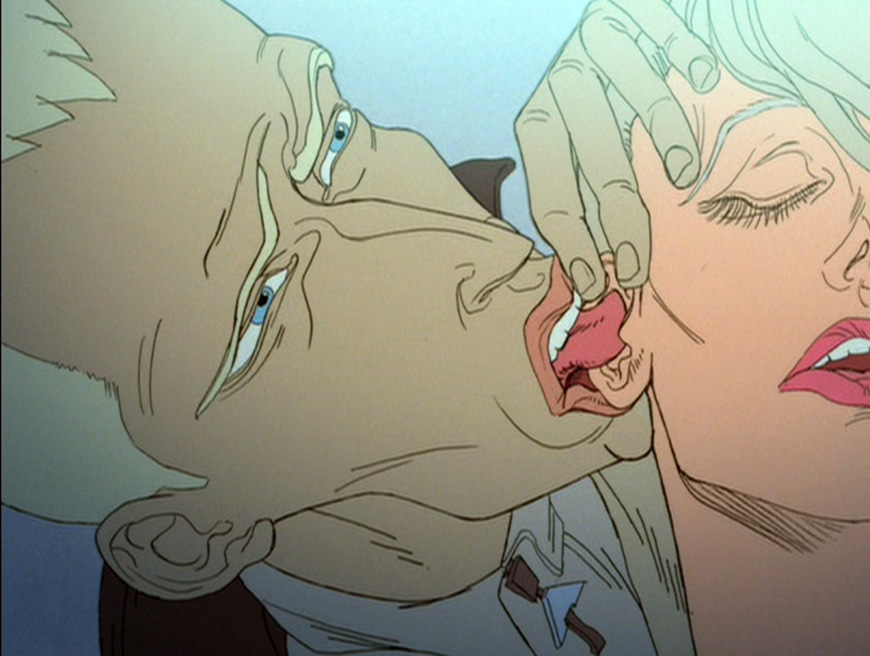

This core visual would later go on to bookend the full length title sequence for Æon Flux’s ten episode run of half-hour episodes. While the repartee between Æon and Trevor serves as a centrepiece amid the sequence’s dynamic visuals and idiosyncratic score, their words reveal only the most perfunctory slivers of their relationship and intent. Triple entendres later revealed as feints in a unending game of wills, where the truth more often lies far from what is said, but at periphery of what is seen.

A discussion with Æon Flux Creator PETER CHUNG and Composer & Sound Designer DREW NEUMANN.

What were the first production meetings for the Aeon Flux title sequence like? What sort of themes and ideas from the shorts and series did you want to incorporate in the show’s sequences?

Peter: You know, it’s funny. I always regretted having to create that sequence [for the half-hour series]. In the end, I think it turned out well, but I actually always prefered the Liquid Television version of the title sequence, which is just a close-up of the eye with the fly crawling up the face. That was what I originally wanted to use, but MTV thought that wasn’t explanatory enough.

—Peter ChungI actually always preferred the Liquid Television version of the title sequence.

Æon Flux (1991) pilot main title

Peter: So they really pushed us to deliver a sequence that had narration and gave background on the characters and their relationship. And so, that’s why it ended up the way it did. There was a lot of pushing back on our part, myself and the rest of the creative staff, to not stray too far from what the original shorts had been because I had never thought there was going to be a half-hour show. I was just doing the shorts for Liquid Television. Then, at the time, MTV was looking for more original animated programming and, while they tested shorts from the series, Æon tested very well. So that’s really the motivation behind expanding it to a half-hour.

Æon Flux Creator Peter Chung

They often didn’t understand what I was doing with the show, so I had to be pretty cagey about being to candid about what my real interests were at the time. A lot of it is artistic concerns. I wanted to make a show that was, not just for me as an artist but for the viewers looking for that sort of content, something that could be considered art on commercial television. MTV had no experience in making original content, so they just let me do what I wanted to do. At the same time they were very strict about broadcast standards and practices. We used to get notes that were just absolutely ridiculous, like you could never show a shot of a woman’s body that did not include a head, because the censors deemed that as objectifying. The thing is, in the original shorts I used all kinds of angles, like the shot inside the character’s mouth or really low angles from a pool of blood. And that’s the stuff that people liked, when they were focus testing it. But when it came time to make a series, it was as if they decided that they weren’t going to allow us to do many of the things that made the show so appealing to begin with and that was very frustrating.

Drew, you were the series’ sound designer and composer. What were some times where the production of the show’s sound design came into conflict with MTV’s broadcast standards and practices?

Æon Flux Composer and Sound Designer Drew Neumann

Drew: Well, the gunshots weren’t a problem on the shorts because they were fairly low budget and they hadn’t really thought through concerning themselves with those things at that point. Like, “Eh, it’s Liquid Television, it’s a compilation animation jam.” Peter’s thing was that he wanted to present an antihero view of ultra-violent material. So yeah it was violent, but it was violence with the intention towards an anti-violence statement. Building excitement only to make the audience uncomfortable in unpacking what motivates that feeling. Same with the whole S&M aesthetic, skimpy costumes, and sexually suggestive moments. Again, it’s trying to play off the dichotomy between sex and violence; you’re not meant to feel comfortable about either thing. There wasn’t any feedback on what sounds to use for the shorts, and that didn’t change much with the move to the half-hour series. The only notes I ever got from MTV were from that first short over why I was doing orchestral music. But Peter backed me up on that one because he was the one who requested that.

Where and how did you record the sounds for Æon Flux?

Drew: During the time of the Rodney King riots, I was up recording gunshots at a firing range where the DEA happened to be practicing. Given the timing of what was going on, they were reluctant initially seeing this guy with a microphone recording them, though as soon as I told them I was working on a cartoon they were super helpful. I got some wonderful 9mm sounds and gunfire echoes from that session, because the range was in a boxed canyon. That’s where the sound for Æon’s gun came from. Towards the end though I felt that the character was missing a personality. So I had Mary Granfors go into a booth to record some wild moans and guttural voicings to achieve that. She was the editor for the show and just so happened to have this smoky voice that was a perfect fit for the character.

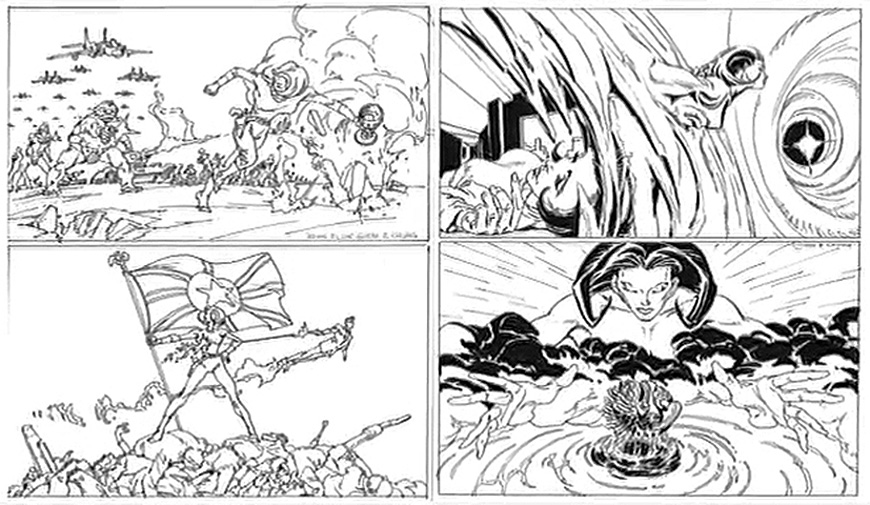

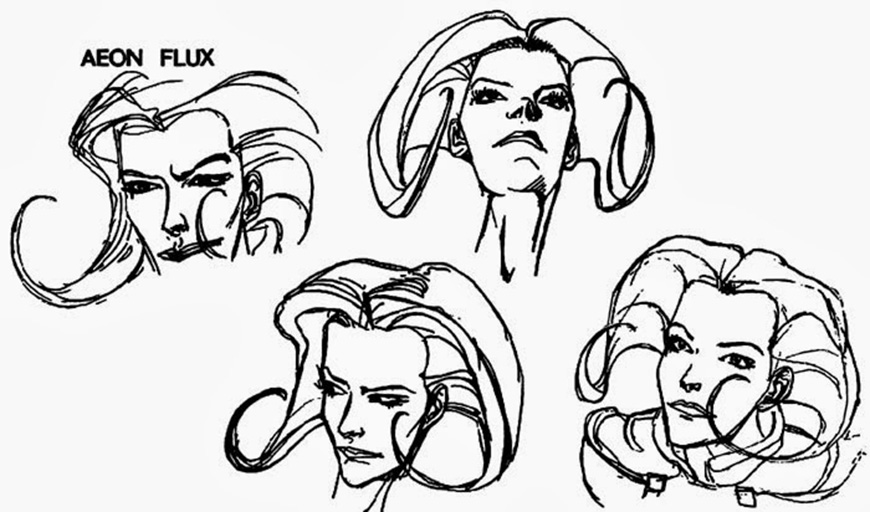

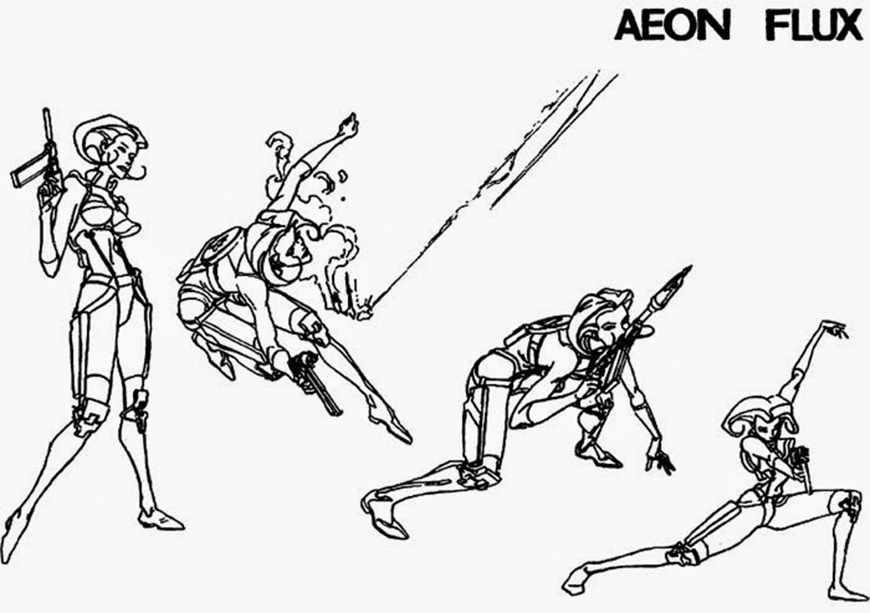

Original Æon Flux pitch artwork

And as the series’ composer how would you describe the music of Æon Flux?

Drew: I would say kind of “cyber-ethnic.” There are two thematic threads behind the music of Æon Flux, which are order and chaos. So the music that expresses the world of Trevor Goodchild, the leader of Bregna, was intended to be sort of dictatorial and rigid and orderly, with a sort of a corruption underneath, and the music for the Monican side was supposed to represent passion and chaos. It’s a little less European sounding and more industrial, with found sounds used as musical instruments. But they’re primarily two different worlds of music that jump back and forth.

Original Æon Flux pitch image

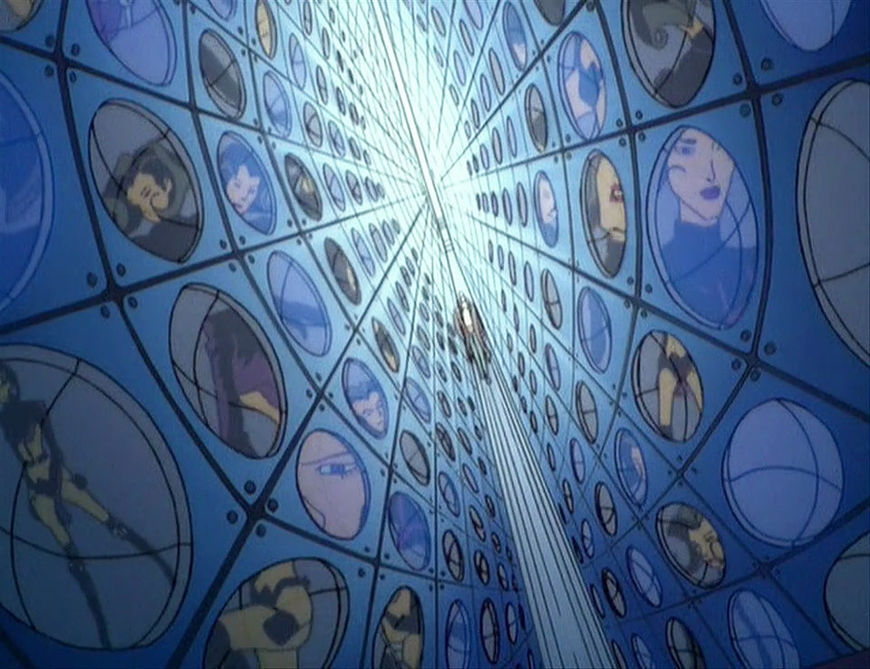

One of the most persistent themes throughout Æon Flux is that of surveillance and voyeurism; of the power inherent in the act of seeing and being seen, something which is represented in what is arguably the series’ most iconic image: an eye enveloping a fly between its lashes. What first inspired the idea behind that image?

Peter: The creative process is often very circuitous in how things come about, but there’s a couple things that I could relate to that. There was this show I caught briefly while on a trip to Japan many, many years ago that had this close-up of an eye with a very long eyelash. And that image had just haunted me for years. I work a lot late at night, so I end up taking a lot of daytime naps after lunch. And very often I used to get these episodes of sleep paralysis. I would have cases where I struggling to open my eye and it really felt as though my lashes were stuck together. And I remember doing an illustration in coloured pencil of just a close-up eye with the lashes stuck together, just struggling to look between them. I had it hanging on my wall for years, it was this kind of strange almost landscape image of a psychedelic eye. I had always wanted to animate that scene, and only later did the fly come about which gave it an element of movement and conflict. And it suggested a lot of things, like a killer or a venus flytrap.

—Peter ChungThere was this show I caught briefly while on a trip to Japan many, many years ago that had this close-up of an eye with a very long eyelash. And that image had just haunted me for years.

Storyboards for the Æon Flux pilot opening title sequence

Peter: The character of Æon is someone who’s always scheming. What you were saying earlier about voyeurism, she didn’t speak in the beginning. So it was about using your observations to figure out what was going on. A good film or story is one where you can understand what’s going on in a character’s head without being told what that is. Once they start to explain through words, that defeats the purpose behind using the medium of film. It’s not just that film is a visual medium, it’s that the way we understand events through our senses is fundamentally different than how we understand them through text. We become more invested and are required to engage with it on a more intimate level, purely through our sensory input.

Drew, when Peter first approached you to score the pilot for Æon Flux, what was your first impression? How did the pilot’s aesthetic inspire or influence your musical approach?

Drew: Well, the first thing I saw was storyboards. I didn’t actually physically see him for months probably until after the shorts were done, because he was there living under a desk and working on the show. He’d send me the boards and it was really hard to tell from them what the hell was going on. I mean, straight through to the half-hour series it was like, “Yeah, you can send me the storyboards, but I really can’t tell from this.” And that’s a unique thing. Usually from animatics you can look at them and go, “Oh right, I know what’s happening here”, but with this it was like a carefully selected and staged scene, but I had no idea how this connects to that. It was like an abstract graphic novella.

Æon Flux character design sketches by Peter Chung

Drew: So, the first two-minute short showed up and they were organizing stuff out of San Francisco with Colossal Pictures and then they’d get them down to me on tape. they sent me a video of the short and it was completely silent. I watched it and my first inclination was to get Peter on the phone and say, “Okay, that had a look about it. What are your intentions, what do you want to do with this musically and who are the sound effects guys so we can coordinate this.” And he just sort of quietly said, “Oh no, you’re doing all of the sounds for it,” and I was like, “Oh, okay” [laughs]. I guess I better plan to do some field recordings then because, y’know, I don’t have gunshots in my library or any of that. Musically, what he wanted to do for that very first short was deceive the audience with almost a parody of the Raiders of the Lost Ark theme with sense of, “Hey, this character is obviously heroic and she’s killing all the baddies that are faceless,” and all that stuff so, I did a demented 7/4 twist on the Raiders theme which was straightforward orchestral with a few elements to set your teeth on edge.

Why do you think Peter chose that theme, for Raiders of the Lost Ark, in particular as the reference point for the show’s music?

Drew: Because the follow-up to that initial two minute was supposed to lead the audience to believe that the character you’re following along is the hero no matter what’s going on. Then you hit episode two, and suddenly it’s flipped; suddenly she’s this psycho murderer running through this bloody landscape. You see the soldiers are people too, huddled in these mounds of corpses littering the building. So the idea was to mislead the audience, only to flip the dynamic and make them question who exactly they’re meant to empathize with. Who’s the good guy? Who’s the bad guy? Peter was playing up the whole idea of moral ambiguity, and so the music had to follow that; to set the tone for that world and anchor the audience in this mood of uncertainty.

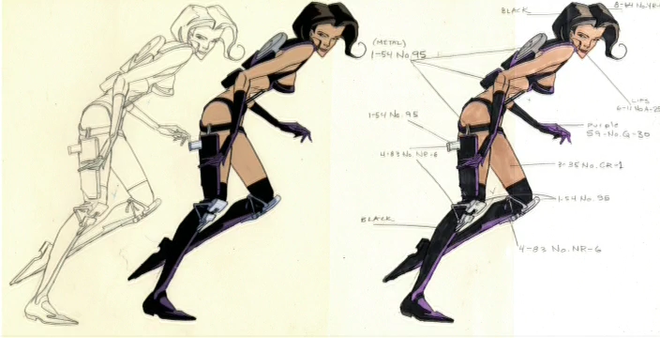

Æon Flux character colour reference card

One of the most interesting stories behind the making of Æon Flux was that the name of the series itself originally referred to only the series, and not the character who would later become its namesake. So, apart from that association, what does “Æon Flux” mean and what inspired that to be the title of the Liquid Television shorts?

Peter: Well, this goes way back. I had the title “Æon Flux” in mind even before I designed the character or knew who the character was. It was just something that I had been thinking about while creating characters and stories for a long time. I don’t know how it is with other artists, but for me, it’s just a constant process of creating and revising and then finally, this idea I had been gestating for years ended up taking that final form. It was originally attached to a concept that was completely different from what it ended up being attached to. I thinking about the meaning of those words, with “aeon” just being the archaic spelling of “eon” which just means a long period of time as well as a term in gnosticism. Some people have picked up on that, that “aeon” refers to an angel-like figure in gnosticism that’s between human and the divine. I don’t even subscribe to that doctrine, though I like it in concept. “Flux” just referred to the flow of time. I just thought the two words had a good feeling and flow about them, it was mysterious. For a while, I resisted calling the Liquid TV show Æon Flux because I thought that perhaps it was too obscure or that I should save it for something else. At the time, I thought it was just going to be the one 12-minute series of shorts and then I’d be done. It ended up becoming something much bigger.

Drew, how did you approach composing the themes for the respective title sequences?

Drew: When I first saw it I thought, we’re way up close on this eyeball, so I need to find a wet noise for her eye is rolling forward. I needed to record a fly which, as it turns out, is impossible. So instead I took an alarm clock and waved that around my studio shotgun mic to simulate that sound. The underlying tone actually was, I put contact microphones on a cardboard tube and then put a duster can on the other end of it so I could pick up a sort-of dusty, airy sound. And then I dropped that on to an Ensoniq keyboard that had polyphonic aftertouch so I could open up filters and make it swell like an instrument. The sound for the eye closing was just swishing a finger across a piano chord really fast to startle the listener. The idea behind that sequence was to say that she can act without thinking. She's so badass, she can stop a fly mid-flight with nothing more than her eyelash. And not only that, but focus on it, which is the creepy part [laughs].

Stills from the Æon Flux pilot

Drew: Then with the half-hour series, Peter insisted on recording dialogue in a very somber, low-key level. He didn’t want the over-the-top drama of other kinds of shows. It’s the bane of my existence doing title sequences with characters chatting over them like say, Wild Thornberrys. I figured I would just go with a riff on what I had done for the short episode ‘Gravity’, the one where she’s falling out of the airplane. There was some political-sounding music in the background when we cut into the interior of the plane, like a Breen dictator giving some anthemic speech in the vein of 1930’s Nazi Germany. I tried to start off subtle with a simple operatic theme underneath, like a marching chant. And then we truck out to a shot where, I think Peter nearly killed some animator over back in Japan over that shot, because it was so complicated that only he could properly animate it. We see Trevor roaming through this walkway and then we get into the real meat and potatoes of the Æon Flux theme, where I was able to get out from under the dialogue and push the music harder. The music had to abruptly shift to reflect Æon and her character. The original leitmotif is echoed throughout the entire series in some form or another.

Let’s talk a bit about the usage of dialogue in the longer sequence. While other shows of their time would have preoccupied themselves with the ‘who, what, where, and why’ of the series, Æon Flux’s titles are centered around a fragmented conversation between the characters of Trevor Goodchild and Æon herself.

Peter: Well, what I wanted to establish was that that was the main thread of the series, which was the conflict or relationship between Æon and Trevor. There are no other recurring characters besides them. There was a lot of push from MTV to have a lot of narration, some kind of narrator in the show itself. They suggested having Aeon Flux provide some narration to offer some sense of exposition from which to open the show. I absolutely fought against that idea; no way. That’s just absolutely antithetical to who that character is, so the compromise we reached was to make Trevor the “narrator” of the series. You’ll notice looking back at the show, not all the episodes but a lot of them open with some sort of narration from Trevor. That worked a lot better because Trevor is a politician, he cares about making an impression on the public, whereas Aeon couldn’t care less. That carries throughout the series, I didn’t want her voice to say anything that was expositional but rather what captured her attitude and personality. And I would have to say that a title sequence which directly inspired Aeon Flux’s was the one for the British television show The Prisoner, which has a back-and-forth between the main character and his captor.

—Peter ChungA title sequence which directly inspired Æon Flux’s was the one for the British television show The Prisoner.

The Prisoner (1967) title sequence excerpt

Peter: It’s worth noting I didn’t actually write the dialogue in that opening title sequence. That was one of the other writers on staff. I resist dialogue as much as possible. I come up with the plotline and structure and usually work with different people to flesh it out.

How long did it take to animate the respective title sequences from storyboarding to final cut? What tools or software did you use to put it all together?

Peter: Well, there was no software. This was all done traditionally with paper, pencil and hand-painted cells and then shot under a 35mm film camera. You gotta remember, this was the early 90s [laughs]. The original title sequence, once I knew that was what I wanted to do, that was simple to execute. It wasn’t a particular difficult thing to draw or animate because it was a pretty simple image, just a walk cycle of a fly moving across the screen.

Still from the longer Æon Flux title sequence

Peter: The longer sequence for the half-hour show went through many different iterations in the storyboard phase. We were doing it at the same time as we were working on the show, and we were still trying to figure out what the show was going to end up being, because we were inventing it. I worked very closely with the animator you mentioned earlier, Osamu Tsuruyama, on the that title sequence. He actually did a lot of drawing on the storyboards and worked on the show as a designer, though he was a director in his own right. I script everything out before anything is storyboarded or animated. I would have liked to have used the original version but, once it was done, I was in fact very happy with how the half-hour opening turned out. I have no misgivings about it.

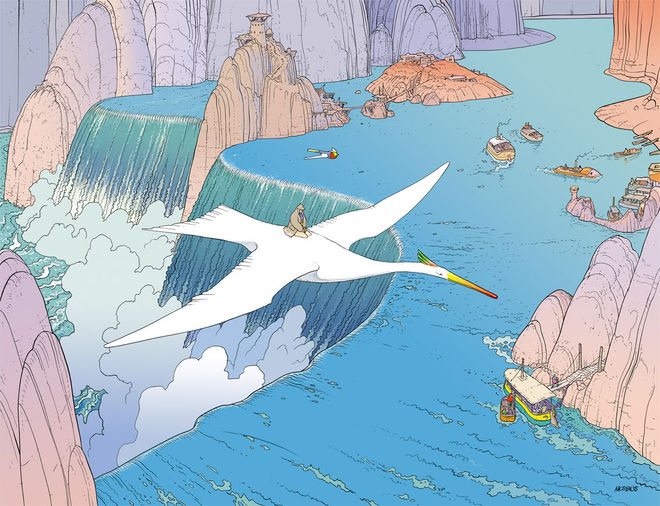

Let’s talk a bit about the visual inspirations behind Æon Flux. While some have tried to describe the show as ‘anime’, it’s perhaps more accurate to call it avant-garde; its aesthetic drawing inspiration from the paintings and drawings of Egon Schiele and Jean “Moebius” Giraud. How were you first introduced to their work, and why do you feel that it left such a profound impact on you?

Peter: It’s a combination of the cinematic approach to directing animation that we see in Japanese animation. I’ve always loved Japanese animation since I was a kid, but one thing that’s always bothered me about it was the design of the characters. And I always wished, well, if you could have this kind of cinematic animation storytelling without this horrible cutesy character designs, that was something I wanted to see. I was looking at a lot of Moebius at the time, I had actually gotten to know him and work with him on a project early in my career. I really admired and was inspired by him as an artist. What I love about his approach to comics and graphic illustration in general is that it has a clarity to it. The term in French for that is “ligne claire”, which means clear line. The main practitioner of that was Hergé, the creator of Tintin. It’s a style that’s very descriptive, and what that means is approaching the subject with a certain amount of graphic neutrality.

An example of the ligne claire or "clear line" illustration style by Moebius.

Peter: I think of images on film not as visual elements, but as an event unfolding in time. The reason I chose animation as a medium is that it’s about the orchestration of how you’re using time and the progression of an event as much as it is about the composition, graphically speaking. You’re composing using time. And in order to do that, I think it’s important not to emphasize one graphic element over another. When I’m talking about elements, I’m talking backgrounds, props, characters; all those things have equal importance in conveying an event. It’s not just the character. A lot of times what you see in comics and Japanese animation are attempts to provide atmosphere with light and shadow, and I think that’s the wrong way to go about the medium. Drawings don’t have any lighting, that’s fake; you’re just simulating a light source. So it kind of defeats the purpose to try and play that game. You can do it and do it beautifully, but I’m more interested in being descriptive and less about atmosphere. My favourite filmmakers are like that, they’re very lights-on like Hitchcock and Kubrick. My favourite film is Jacques Tati’s Playtime and that epitomizes that approach: lights-on, descriptive, and very neutral. You’re not trying to obscure something in shadow and contrive mystery. There’s already mystery in the event itself. My stories have ambiguity, so I don’t want them to be ambiguous portrayals of an ambiguous event, I want them to be as clear a portrayal of an ambiguous event as possible.

A still from Jacques Tati's Playtime (1967)

Peter: What’s funny is that, very often people ask me, “Well, why couldn’t you just come out and be more linear or be more explanatory about what’s going on?” And then, they would come back and say, “This is what I got out of it, but I’m not sure.” Very often they actually understood it perfectly, they just had a doubt that that was what I was intending to convey. So the problem wasn’t that the filmmaking, storytelling, or direction was obscure, it was that the idea itself was unconventional and they weren’t expecting to see that. It’s very important for me to communicate an idea clearly. I’m really not making films for myself, I’m making them for an audience. Despite what some might say, you can’t really make films for yourself. It doesn’t make any sense. I think if someone says that, and genuinely means it, they don’t understand the medium they’re working in. Because film is a medium of mass communication, that’s why it exists. I can understand if that if it were with paintings and drawing, but the purpose of film is to project an idea to an audience. The reason why all the principles of filmmaking exist is because of how they affect an audience, not because it provides pleasure to someone through the act of the creative process.

You’ve cited such directors as Federico Fellini and Alejandro Jodorowsky, animators like Yoshinori Kaneda and Koji Morimoto, and even colleagues such as Osamu Tsuruyama and J. Garett Sheldrew as influences on your work. Who are some of the artists and animators you look to now for inspiration?

Peter: Well, it’s funny. I studied the traditional American Disney style of animation when I went to CalArts, and after that I went through a period of admiring Japanese and independent animators. But to answer your question, I find a lot of inspiration from old time classical American animators, like Hollywood animators. A lot of Warner Bros. stuff. In particular, the one that really stands out to me is an animator named Rod Scribner, who did a lot of work with Bob Clampett on Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck. That’s mostly what he’s known for.

An example of animator Rod Scribner's Bugs Bunny animation from "Tortoise Wins By a Hare" (1943)

I think that when you’re starting out as an animator, you’re much more interested in thinking about what the animator is doing because you’re trying to learn. But now as I’ve gotten older, I’m much more interested in what the character is doing. When I look at a piece of animation and completely believe that it’s of a living breathing person, that inspires me. And this extends to filmmaking too. I used to appreciate directors who used a lot of flashy camera tricks. But what I’ve come to realize, after a long time of directing, is that the best directors are able to make films where it doesn’t look like the film was directed at all. Because the characters in a scene are just behaving as someone would, because of who they are, not as what the story or plot would dictate of that scene. And the thing that you realize is that it takes a lot of skill on part of the director to make an audience believe, because it’s all fiction. It’s not true. To me that’s the mark of a real master director.

What are some of your personal favourite title sequences, classic or contemporary? What is it that you admire about them?

Peter: Well, this might be the most obvious answer in the world, but I’ve always loved the old James Bond titles and Maurice Binder’s work in general. There’s some great older Japanese animation shows that I’ve thought had great title sequences, though I don’t watch a lot of television nowadays. It might sound strange, but one of the ones that really sticks in your mind after a while is the one for Gilligan's Island.

Gilligan's Island (1964) main titles

Peter: And another one is the title sequence for the Beverly Hillbillies, because they pack so much into such a small amount of time and it really preps you for the experience of what the show is going to be. The ones we have now are, I mean there’s some beautiful work that’s being done today for television, but I very often find myself skipping over those if I’ve already watched it once. I’m a child of the sixties, so the Barbarella sequence I loved [laughs].

Barbarella (1968) main titles, designed by Arcady/Maurice Binder

Peter: The one for Enter the Void is one I could always watch over again, along with anything Saul Bass has done.

Drew, who and what are some of your favourite composers and themes? In your opinion, what distinguishes a good theme from a great theme?

Drew: Well recently, Jeff Beale’s work has really impressed the hell out of me. Ramin Djawadi’s Game of Thrones theme is an obvious one. John Williams, definitely. Thomas Newman, and some of Danny Elfman’s stuff too. Jerry Goldsmith, one of the most versatile composers of his time. He could do futuristic alternative synth stuff on Logan’s Run or the beautiful work he did on Poltergeist. So I guess there’s really two areas of themes that you have in cartoons: the kind where you don’t really have time to say much, you’ve got a leitmotif and then get out. And then you have the type of themes that are similar to feature films, where you basically have to come up with the musical equivalent of a paragraph. You’re not just saying a sentence, you’re establishing a theme on a series of variations and repetitions. If you analyze any of John Williams’ themes, it’s something that bears repeated listening. It’s a paragraph. Same thing for Howard Shore’s work on Lord of the Rings. I think one theme, in particular, that was directly influential on Æon Flux was Twin Peaks’. Musically, it didn’t relate to it all that much, but it sort of sparked those initial ideas.

—Drew NeumannI think one theme in particular that was directly influential on Aeon Flux was Twin Peaks’.

Twin Peaks (1990) main titles

Peter, you’ve spoken before about how Æon Flux was created out of a desire for an answer, or critique, of what you described as the perverse moral absolutism of heroic violence and a manipulation of sympathy inherent in Hollywood cinema. Do you feel that model of morality is still dominate throughout American media, or has it morphed into something else?

Peter: I think that in movies, yeah. If anything, it’s become even more pronounced. Television, I think there has been a lot of evolution. I think it’s much more possible now to create stories that are more morally ambiguous, where it’s not just about good versus. It’s the movies that have become much more morally simplistic. I guess it really started with Star Wars, the struggle of good versus the evil empire. We’re good and they’re bad, and that’s that. I really hated the Lord of the Rings stories for that same reason. If you were an orc, you were evil; you were born bad. It had nothing to do with what you saw or wanted. I thought it was very racist in its implications. This race is bad but if you’re a hobbit, you’re good. And those two examples just compounds this notion that the world is in this eternal struggle between the force of good and evil. I don’t believe that that’s true, and I also don’t think it makes for good drama. And even if you told me there was a force of absolute good and a force of absolute evil in real life, I still wouldn’t want to make movies about that because dramatically speaking, there’s nothing interesting about that. Æon Flux was as much a reaction against that as it was creating an animated series for adults. And, in a lot of people’s minds, the first thing that a lot of people thought [back when Æon Flux was being produced] was the answer to this was putting in high levels of sex and violence. But that’s not what makes something adult. What makes something adult is the ability to cross certain moral boundaries which, if you were a kid, you probably shouldn’t or probably wouldn’t. Kids do not have a very developed sense of the nuances of moral choices; their moral compasses haven’t developed yet. With the problem itself, I’d be careful about that.

Still from the longer Æon Flux title sequence

Peter: What I was really interested in was creating a show that was about morally ambiguous stories and characters. Æon isn’t always the hero and Trevor isn’t always the villain. They’re both motivated by good intentions, what they think are the “right” intentions. I just think that most of the conflict that arises in real life, what I’m interested in, is people trying to approach a problem from a different point of view and in the end it comes down to something very personal instead of some impersonal cosmic sense of absolute good. To me, that’s not the world I live in. A lot of the conflicts in the half-hour episodes don’t need to exist at all, because there’s nothing inherent that causes the two characters to be against each other. What brings about conflict is misunderstanding, or distrust, rather than something inherent in the situation. In some of the episodes, what you’ll see is that the characters want the same thing, but they’re afraid of what the other character is doing because they distrust them. I would say a lot of real life conflict is like that.

As the show’s creator, why do you think Æon Flux was so singular of its time that, nearly twenty-five years later, people are still discovering it. What makes the series so enduring?

Peter: There’s different ways in approaching that question. If it’s what is it about the show in its final form that enables it to continue to generate interest from new viewers and new audiences, I would say it’s the fact that I was – let me put it this way, I was intent on engineering the show from the very beginning to be something that you would need to watch more than once. That it would be very dense, both narratively and thematically. Honestly, I look back on these episodes now and I could have easily extended some of these into 90-minute features. Because there’s so much going on in each one. It was the intent that there would be so much stuff packed into each episode that you’d want to rewatch it, maybe not right away but perhaps a year later. People tell me that’s what they do, they’ll watch it and come back to those episodes years later. I think any filmmaker would want that to be the case, but it’s not accidental; it doesn’t just happen by chance. You have to follow a strategy for that to be the outcome. And that’s a long and complicated process.

In terms of your own work, how would you describe the particular philosophy underlying your process?

Peter: When you look at a movie, you must think of the ways it’s designed and directed as a way of providing a vehicle for a story. And in general, I think that’s what people think. They think that, well the main point of the content exists in the story, and the presentation and way it’s designed is trying to provide a pleasing package so it gets the story delivered to them. But usually, I don’t think that’s the case. Even when someone is watching a movie, they say they’re watching it for the story, I think that’s not true. I think that what excites you and interests you and keeps you engaged during the process of watching a movie or TV show is not the story, it’s how the story is told; it’s the presentation and direction. The story is a pretense for directors to direct. If I’m a director, I need something to direct. I need some raw material to practice my craft. And that’s what the story is, it’s the raw material for a director to direct. The story, to me, is just a bunch of made up stuff that didn’t really happen and in the end didn’t really make any difference to anyone’s life. I honestly believe that. Because it’s a work of fiction and you can make anything happen that you want. If you spend enough time writing enough stories, you know that’s true because you can bend a story to prove any point you want. You could write a story where crime doesn’t pay, or you could write a story where, “Well actually, crime does pay.” You can literally arrange events in whatever way suits you. A work of fiction has no absolute authority to deliver that kind of message, because it’s fiction, and it’s just a frame for the author.

—Peter ChungI’m not interested in whatever message a story can deliver. That’s a smoke screen.

Æon Flux (1996) video game teaser designed and directed by Peter Chung

Peter: So to me, the story is just a way for allowing the audience to experience a change of consciousness that comes out of watching a film or something. And that’s what I’m interested in because I’m not interested in whatever message a story can deliver, that’s a smoke screen. But what is not fiction, what is real, is the actual train of thought and realizations and moments of “aha, I understand!” and the way you perceives meaning during the course of watching a story unfold, that’s what I’m interested in. I would have to say that’s what art is for me. It’s not a way of delivering any kind of moral messages or any of that, it’s about proving the audience to an opportunity to discover meaning in something about themselves, personally, through the reflection of fiction. And so, whether everybody agrees on what that meaning is is secondary. It’s the act of perceiving meaning itself which is the goal. To me, that’s why it’s very important for the way a story to not simply deliver answers or explanation. It requires you to use your meaning-making faculties.

If you were to talk like this in a studio network environment, they would say you’re crazy. Or they’ll say, “Well, who cares about that? That’s just obscure and esoteric.” And what I try to tell people is that look, there’s nothing esoteric about that at all because that’s what you’re doing constantly. If you go through the course of a day— y’know, the reason why you’re a human being, the reason why humans are different from animals, is that your mind is constantly perceiving meaning. We’re meaning-making animals, that’s what makes us human. To me, that’s everything. It’s not esoteric. You’re constantly engaged in that and it’s unavoidable even when you’re watching a movie that doesn’t set out to do that intentionally, you can’t help but do that. And what I’m saying is that what motivates me is to create those moments intentionally. Because very often, I’ll watch movies and take something from that experience that I’m all but certain the director did not intend. I think a filmmaker needs to be aware that that’s what’s happening and to have some kind of control over that, because to me that’s what makes the creative act exciting.