“Most of what follows is true.”

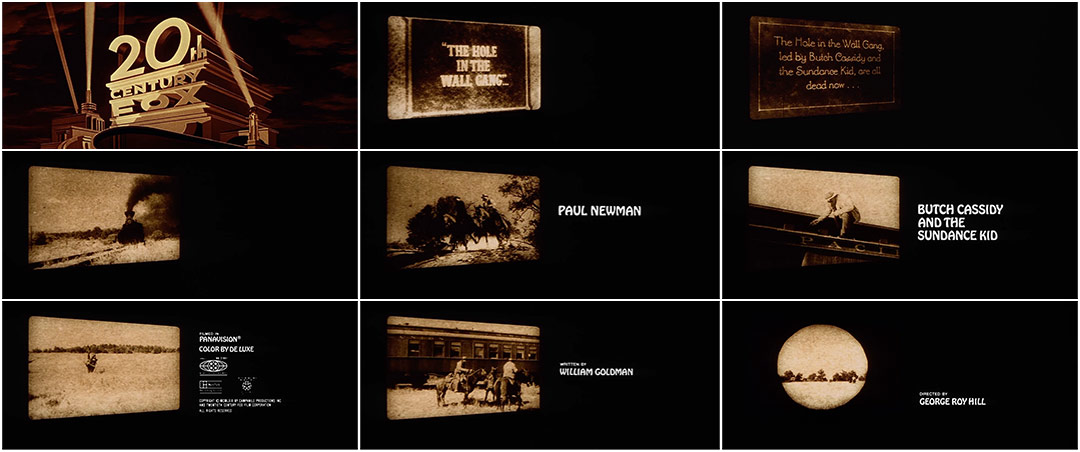

As the sepia-toned newsreel acts out the story of real-life bank robbers Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, we already feel the nostalgic hush of a legend long gone.

At times, a title sequence outshines the film that follows, at others, it’s a missed opportunity. This one, however, wears its seams face-out, calling attention to itself while maintaining an intimate hold on the larger themes at play. Both prologue and epilogue, this title sequence runs through the events of the film in a way that is at once revealing and reticent. The sepia tone, beginning with the tinted 20th Century Fox logo, carried through the title sequence, and paired with a melancholy piece of music composed by Burt Bacharach, places the story firmly in the mythic past. The newsreel fittingly resembles the famous 1903 short The Great Train Robbery and sets the proceedings up as a metafilm – a film acknowledging its own artifice. We wonder: how much of this is true?

Even Hobo, the main typeface used in the credits, bears its own legend. According to stories, it was sketched in the early 1900s and sent with no identification to the foundry, where it languished in production for so long that it was called “that old hobo.” It was eventually patented in 1915 along with Light Hobo.

Looking at the film as a whole, much of its brilliance can be chalked up to William Goldman’s incisive screenplay, which featured a wealth of clever banter and helped to bring the Revisionist Western genre to new heights. The product of six years of research into the infamous turn-of-the-century outlaws, the screenplay sold for $400,000, the highest sum of money a screenplay had ever been sold for.

The "Fort Worth Five Photograph" featuring Butch Cassidy's Wild Bunch gang. Taken by photographer John Swartz in Fort Worth, Texas, 1900.

It’s somewhat ironic, then, that the sequence initially penned by Goldman and shot as a scene that appears later in the movie was revised into a title sequence. In the original scene, as the two men watch the newsreel of their gang robbing the train and then being gunned down, they shout at the indignity of their portrayal and the stoic Etta Place (Katharine Ross) unceremoniously leaves them to their fate. In context, the scene was deemed heavy-handed and unnecessary; however, instead of cutting it altogether, director George Roy Hill moved the newsreel to the beginning, to act as the title sequence. In a scene that initially appeared before the sequence, Etta tells the men:

“I'm 26, and I'm single, and a school teacher, and that's the bottom of the pit. And the only excitement I've known is here with me now. I'll go with you, and I won't whine, and I'll sew your socks, and I'll stitch you when you're wounded, and I'll do anything you ask of me except one thing: I won't watch you die. I'll miss that scene if you don't mind.”

By placing the newsreel at the fore, Etta’s line bears more weight, harkening back while it foreshadows, and simultaneously calling attention to the mechanisms of the story. The film is made stronger by not only the removal of a scene which in context felt contrived, but by its insertion at the very beginning of the story, giving it depth and complexity.

Robert Redford as the Sundance Kid, Katharine Ross as Etta Place, and Paul Newman as Butch Cassidy

Director David Fincher, when describing how Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid inspired him to be a filmmaker, had this to say about its title sequence:

Butch Cassidy & the Sundance Kid has an amazing title sequence that was originally a sequence in the movie. It featured Katharine Ross, Redford, and Newman in Bolivia, where they see a film about their own exploits. It’s a beautiful idea for a scene and it also made for an amazing title sequence because it set up the idea of the Western as something we’ve come to know through the movies. The film was such a revolution in terms of thinking about the Western and in terms of buddy movies! I look at that movie and its title sequence and I think, “That was a scene in the film – that was written in the script – but it was used in a completely different way.” They decided maybe it was too dour or negative, that maybe the ending would be more provocative without teeing up the events.

I can’t think of many great title sequences to movies that I dislike, so it’s as much about it being a good title sequence as it is about it being a movie that I enjoyed. That’s when they stand out.

On its face, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid is a finely rendered Western about a pair of smirking antiheroes whiling away their time in the American West and South America. But just as Butch Cassidy named his gang after a pre-existing one, a man so aware of the power of myth in the West, so too does George Roy Hill exploit the existing tropes of the Western, winking knowingly at his audience while delivering a tall tale. The end, when it finally comes, feels like a dim, caramel-coloured memory.

Read more about the making of this film in Behind the Camera on Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid from Turner Classic Movies.

Main Title Design: Glenn Advertising, Inc.