Some movies don't get their proper due, and Bernard Rose's 1992 horror film Candyman is one. Based on Clive Barker’s tale The Forbidden, the film is built on a foundation of complex themes and real-life events, with a storied production to boot.

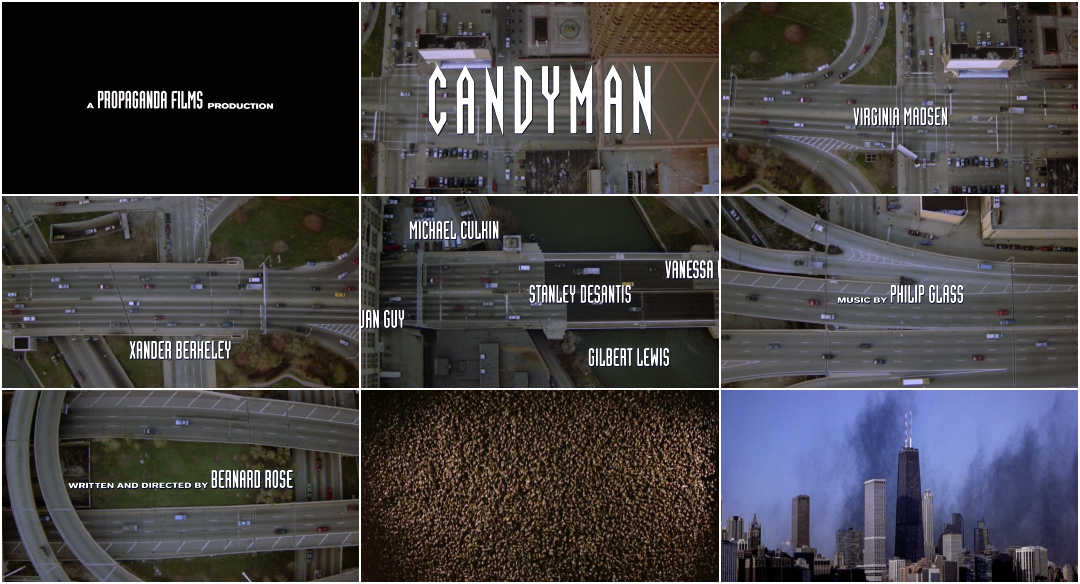

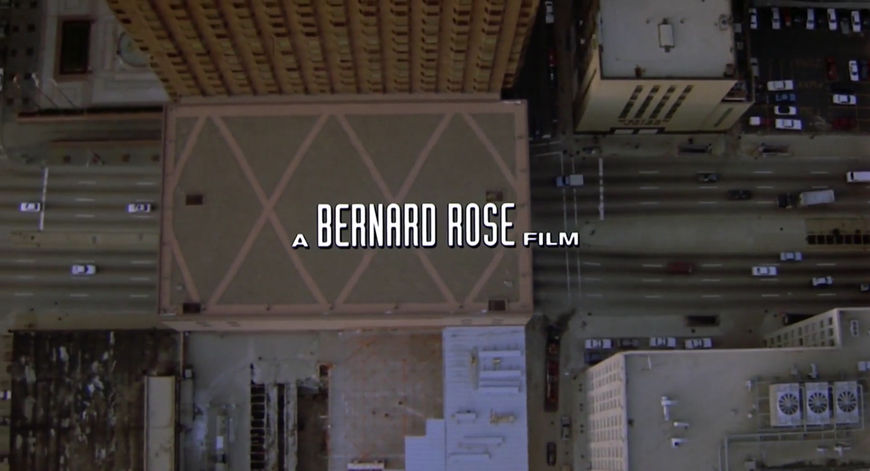

The opening of Candyman is an elegant and ominous overture to a brutal and tragic narrative. The title sequence features a series of flowing aerial views captured by helicopter pilot Bobby Zajonc looking down on the winding freeways of Chicago, its Hitchcockian influences laid bare, setting up one of the major underpinnings of the film: architecture as a malevolent force. The credits, designed by studio Heart Times Coffee Cup Equals Lightning, zoom in and out of frame to mimic the smooth movement of the cars below. Elevating all of this is a fantastic synth and choral score composed by Philip Glass, celestial and foreboding, portending doom while lulling with its grace.

As the final credit – Written and Directed by Bernard Rose – zooms off, the scene cuts to bees. Bees everywhere, crawling over each other, too close for comfort, their tiny sounds made gigantic, and then that voice. Tony Todd is the Candyman and his rumbling baritone calls to us, introducing what’s to come in no uncertain terms: I'll split you from your groin to your gullet. The words and the voice vibrate into your core. The Chicago skyline is then shown engulfed by bees. The last scene of the opening and the segue into the film proper is this shot of the city, Candyman's territory, overlaid with the face of Helen (Virginia Madsen), blonde and bright-eyed, a prototypical Hitchcock heroine.

The haunting of places is a horror standard, but Candyman takes it further, positing the city itself as a malevolent force, swallowing the main characters. What happens when an urban centre is built on top of terrible trauma? Where does that energy go? One need only look at a city's marginalized peoples and its housing projects, the "dangerous" zones, to understand the legacy of colonialism. All so-called "bad neighbourhoods" are places haunted by trauma, and word of mouth ensures the patterns are maintained.

Urban legends have always held a spectacular power, and Candyman – as a figure and as a film – is fuelled by it. The jump scares and moments of gore are certainly effective and memorable, but where the film really shines is in its understanding of the power of myth and words. After all, nearly 25 years on, who among us can stand in front of a mirror and say his name five times?

A discussion with Candyman Writer and Director BERNARD ROSE.

In your mind, as a filmmaker, what should a title sequence do?

Bernard: I like the idea of the title sequence as a kind of mini-overture, before the film started – not necessarily part of the narrative – but as an overture for the mood. And it could or could not have visuals, you know? Obviously the Candyman one does, but I’ve done other ones that are just on black. Sometimes very simple.

I personally quite like having titles at the front. It gives you an opportunity to have a sequence in the film that doesn’t have to rush in. It gives people a chance to sit in and look at the environment of the film and see what’s going on without having to start listening to plot and dialogue. Starting films too fast is always a mistake. I remember in Immortal Beloved, for example, the title sequence is sort of like an overture – there’s just a funeral.

—Bernard RoseStarting films too fast is always a mistake.

Immortal Beloved (1994) main titles, designed by Kyle Cooper at R/Greenberg Associates West, Inc.

Bernard: There is narrative going on but there’s not much. If there weren’t credits there you wouldn’t spend that much time with it, and I think the credits sort of gave you an excuse to say something about the film that was not necessarily plot-orientated but that people wouldn’t get antsy during ‘cause the credits were coming up so they could see it hadn’t really started yet.

It’s the smalltalk before the main event.

Bernard: Yeah! And I think the idea that everything has to start bang-in is a huge mistake. Because… usually they go downhill from there! [laughs]

These things are very fashion-orientated, though. All the credits used to be up at the front, and the films just used to end. I miss credits being at the front. The pendulum swings one way and then it swings the other way. Now the films end and then there’s what they call a “main” title sequence after the end of the film, and then the roller, and no one except the people who are on the roller watch it. [laughs] That never used to happen! [laughs] It always changes. It’s fashion, isn’t it?

When you first sat down to put Candyman together, how did you envision the opening?

Bernard: The whole idea of the opening was actually very planned. It was sort of inspired by the opening credits of North by Northwest.

North by Northwest (1959) main title sequence, designed by Saul Bass

Bernard: But I thought, well, obviously they take place over a static shot, but I wanted to do it over a travelling shot. Which, of course, in 1992 was much harder to do than it is today – to do a shot looking directly down at the freeway like that. So, obviously it was done in a helicopter with a stabilizing mount. Back in that era, you couldn’t point the stabilizing mount at a 90º angle down from the helicopter, so the only way to do that was to actually fly the helicopter at a 45º angle! So, imagine the door is open – it’s terrifying! That’s what we did. I had a crazy pilot – this guy Bobby Zajonc, his name was – so we had the door open on the chopper and we’re flying at a 45º angle and I’d said to follow the cars at the speed on the freeway.

Robert "Bobby Z" Zajonc was also the helicopter pilot who flies Jim Carrey away at the end of The Cable Guy. He has flown helicopters in Twister, Mission: Impossible, Dragnet, and many more.

I went up there and we did a couple of runs, but I’ll be honest with you, with the door open – it was November in Chicago, it was absolutely freezing in there. It was so cold that it snapped the film a couple of times, actually. And I did a couple of runs with him, but then he landed me! He threw me out of the chopper! He was like, “You’re gonna fall out. It’s not a good idea.” I was like, “I’ve had enough too, to be honest,” so I let him do it! [laughs] But he got the shot, for sure, you know?

I know a lot of people who’ve died in helicopters on movies. I’m actually surprised they let us fly over Downtown Chicago like that!

Stills from the Candyman opening title sequence featuring aerial shots captured by helicopter pilot Bobby Zajonc

Bernard: Also, one of the reasons why I hired Philip Glass was I was a big fan of Koyaanisqatsi and I remember there were helicopter shots in that movie looking down and going over skyscrapers. I think that was the first time I ever saw that.

Koyaanisqatsi (1982) opening title card

Bernard: The shot is very different in Candyman because it follows the freeway, but in a sense I wanted the Philip Glass underneath it which was why we contacted Philip who did the music for it. And then the optical part of it was done on an animation stand and optically printed. Originally I didn’t want the titles to come on and stop the way they do. I wanted them to float across, and actually we did shoot it like that, but when we projected it there was too much strobing on the letters. They just juttered across. They didn’t move across smoothly, you know? It needed to be smooth to mimic the visuals, and of course you have to be able to read it. So in the end we just made them come whiz on, stop, then whiz off.

Bernard Rose (right, behind camera) and Virginia Madsen on the set of Candyman

What did you have in the screenplay relating to the opening moments?

Bernard: It just said it was an aerial view.

So it was always intended as an establishing shot for the city?

Bernard: Yeah, but also I always work to design the title sequence which is why it had to be smooth. Obviously again there was no such thing as post-production image stabilization so the shot really is that smooth.

There are also some interesting ideas about urban environments and architecture in this movie. The opening sequence seems to set up the city as this malevolent force.

Bernard: Definitely the film is about architecture and the way that people can exist in the same space, but it’s how the space is designated that affects the nature of the building, in a way.

Definitely the film is about architecture and the way that people can exist in the same space

The segue from the opening sequence into the movie features the Chicago skyline swarmed with bees overlaid with Helen's (Virginia Madsen's) face

One of many aerial shots in Candyman, this one showing main character Helen's car small, dwarfed in the midst of the towers of Chicago's projects

Helen (Virginia Madsen) stands alone on the Randolph Street Bridge above the Chicago River, tiny in the frame

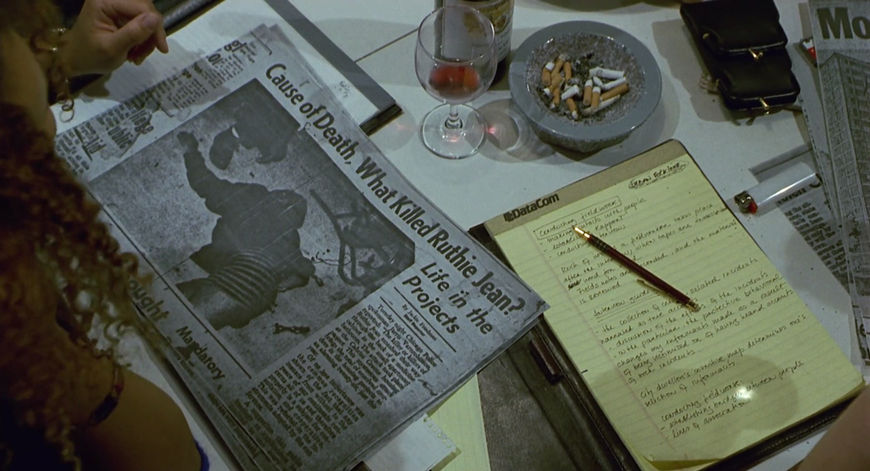

Helen and Bernadette go over newspaper clippings relating to deaths in Chicago's housing projects

Was Anthony Richmond, the cinematographer, involved for this opening as well?

Bernard: It was actually just Bobby, the helicopter guy, who was doing that opening shot. Tony was an old, very experienced cameraman, and Tony took one look at the helicopter and went, “I’m not going up in that! People die in those!” [laughs] That’s actually the correct response, by the way! I know a lot of people who’ve died in helicopters on movies. I’m actually surprised they let us fly over Downtown Chicago like that! Because obviously if we had crashed it would’ve been rather serious! [laughs]

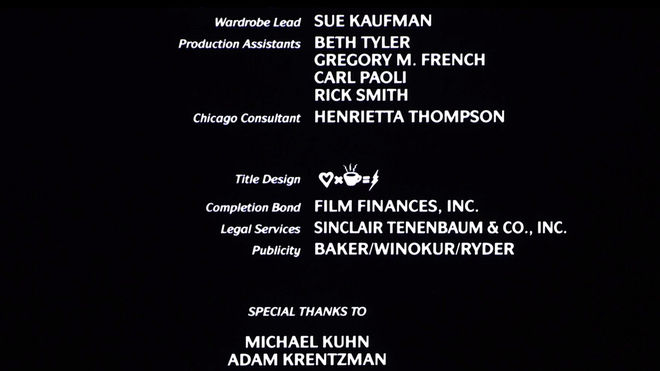

So how did you work with the title designer for this film, Heart Times Coffee Cup Equals Lightning? The credit appears in the crawl as a bunch of symbols, which is pretty rare.

Bernard: That’s right. Yes, I remember that guy because his credit’s a bunch of symbols.

The title design credit in the Candyman end crawl for Heart Times Coffee Cup Equals Lightning

Bernard: They were quite well-known graphic designers in the early ‘90s period. They were friends with Steve Golin at Propaganda and they had big commercial and music video and other businesses so they were doing all kinds of fashionable title design, and he did the title treatment. It’s very kind of pre-emoji, isn’t it?

Yeah, exactly. Designers’ hieroglyphics.

Bernard: They were like the fashionable fancy graphics people in that era, but they were friends with Steve Golin so it wasn’t my hire. They did the title treatment for the title.

Bernard: The actual animation of the titles was done by the optical effects guys, ’cause like I said it was animated on a rostrum camera, on an animation stand. And bipacked together. You can’t really tell, but it’s all one shot, so if you change one thing or get one thing wrong you have to do the whole fucking thing again – and composite it in one go! So doing any change or version of it took about a week and it was horrific. They never actually did it without getting dirt on it. So there’s actually dirt that’s optically printed into that sequence.

Bernard: People don’t notice it anymore ’cause now idiots associate dirt with film artefacts. Of course, when people made films in analog, they did everything in their power not to have dirt on the screen. I remember everyone having long discussions as to whether or not we could accept this because it had bits of dirt on it. Funny, isn’t it?

I said, at the time, who fucking cares? It’s the opening shot, it’s going to have tram lines all over it after it’s been in the theatres for a week! [laughs] Which is true! [laughs] It’s absolutely true, but yeah, those kind of opticals were very hard to do.

And how did you work with Philip Glass? Did you have a back-and-forth?

Bernard: Well, he saw an early cut of the film. I asked him to write – he wrote me basically a suite, and demoed it, and sent it to me. I cut the film to the suite, and then when the film was finished his conductor or arranger came in and redid the cues as I cut them up.

Philip’s a real composer, you know? He’s great. Like I said, I got him from Koyaanisqatsi. I worked with him again on Mr. Nice, many years afterwards.

Mr. Nice (2010) main title sequence, designed by Julia Hall and Howard Watkins

Bernard: Honestly, with Philip you kind of have to know how to work with him. You can’t work with him the way that others normally would: set cues up and give him sequences and the ins and the outs, ‘cause Philip would look at that and go, “Huh?” He writes on paper, for a start! He’s old school.

One last question: Obviously there have been sequels to Candyman, but none that picked up the strands from the first film. Would you ever want to do a sequel with Helen, continuing that particular story?

Bernard: Yes, desperately! I would love to do the proper sequel. There are all sorts of reasons why it’s never happened. I think it would be great, but of course unfortunately I don’t control the rights, otherwise I would just do it.

You think Virginia Madsen would come back to the role?

Bernard: Yeah, absolutely, why not? Yeah, talk it up! Make it happen.