What would you do if you were waiting to hear from your doctor about a potentially fatal illness? How would time start to feel? Would it feel sharply accelerated or laboriously slow? You look in the mirror and remind yourself that you’re still alive. The bustle of life continues all around you, suddenly alien. Something feels definitively off.

Agnès Varda’s 1961 film Cléo de 5 à 7 is about this headspace, following Cléo Victoire (Corinne Marchand), who is awaiting news about a medical test that will determine whether she has cancer. Cléo is a glamorous, self-absorbed Parisian pop star who goes about some everyday activities between the hours of 5:00 and 7:00 p.m. The film’s 90-minute length highlights that for Cléo time has indeed sped up, her life made even shorter in the measurement of its minutes.

Death, decay, and illness can be found in virtually every small, throwaway moment in Cléo de 5 à 7. Egged on by her superstitious assistant Angèle (Dominique Davray), Cléo interprets every small sign as sealing her fate: a broken mirror, a man killed in a crowd, and most ominously of all, the tarot reading that opens the film.

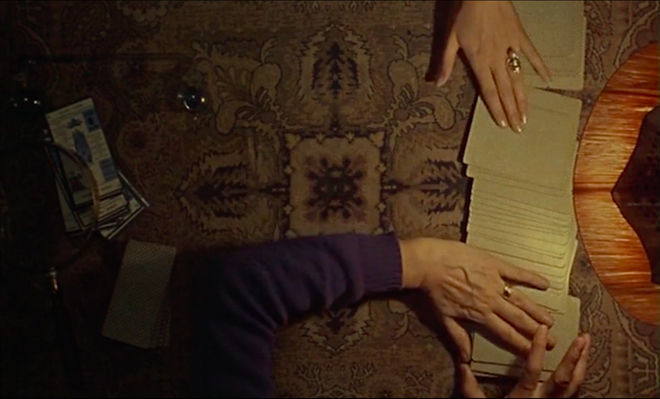

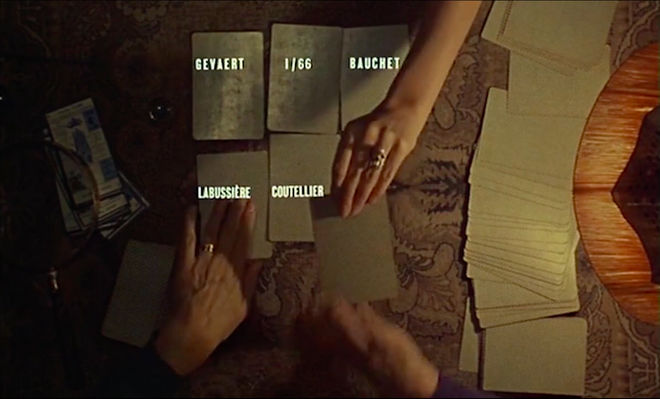

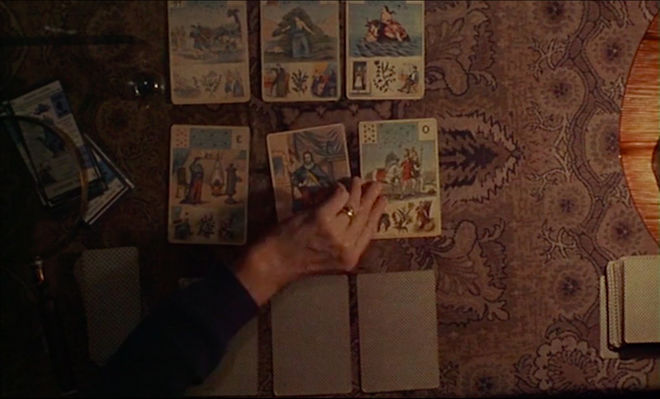

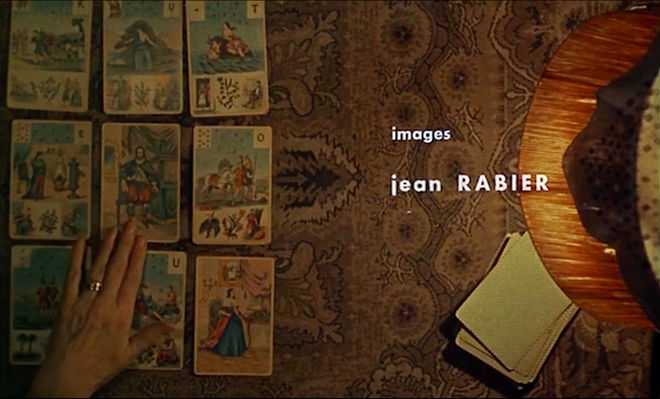

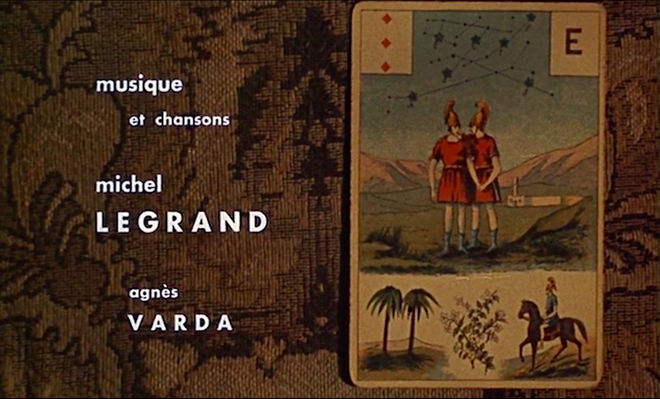

The eerie reading provides an overview of Cléo’s life – her career, lover, friends – as well as an idiosyncratic opening credits sequence, which, unlike the rest of the film, is in colour. It features an overhead view of a fortuneteller’s table with two pairs of hands moving around, their voices heard offscreen. The fortuneteller tells Cléo to cut the deck and choose nine cards.

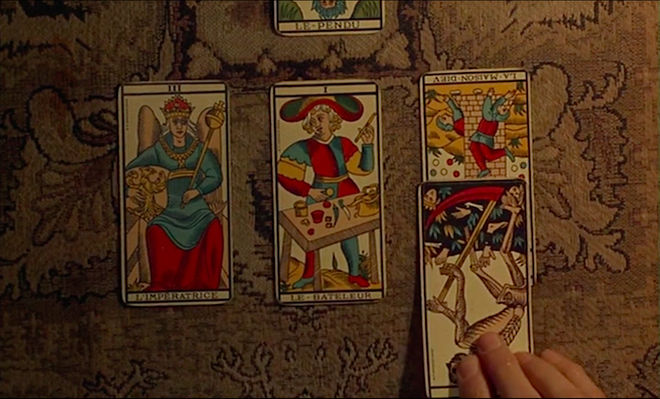

They are spread out in rows of three: three for her past, three for her present, and three for her future. The fortune is fairly accurate – Cléo is a talented musician, she has a strong female presence in her life (likely Angèle), and a generous lover who has aided her career.

Further cards reveal more truths: the toxic introduction of a doctor, a talkative young man, a journey, and an illness, which Cléo confirms as the film shows for the first time her worried face in closeup, followed by a reverse shot of the older woman, all shockingly in black and white.

“I knew it! It’s serious, isn’t it?” Cléo cries out with alarm.

“Yes, but no need to exaggerate,” the woman says firmly, asking her to take one last card.

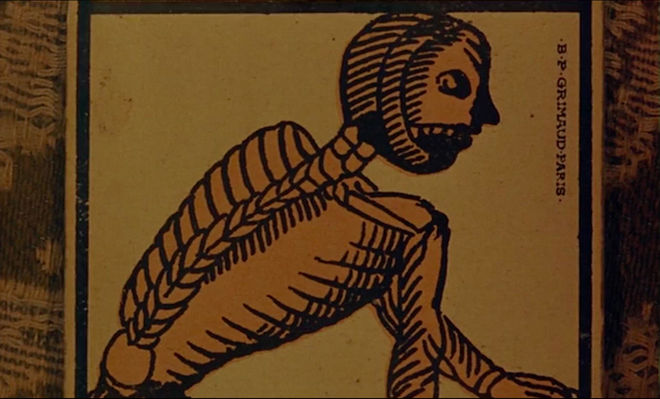

It is the Death card.

“Thanks!” Cléo retorts with equal parts alarm and sarcasm.

“This card is not necessarily death. It means a complete transformation of your entire being,” says the fortuneteller.

But Cléo has already convinced herself that death is imminent. She also asks the fortuneteller to read her palm. Looking at the young woman’s hand, the fortuneteller flatly lies, claiming she can’t read palms. After Cléo pays and leaves, disturbed, the older woman tells a neighbour that she saw cancer in Cléo’s future. “She’s doomed.” This is our introduction to the glamorous, tragic-tinged life of Cléo Victoire.

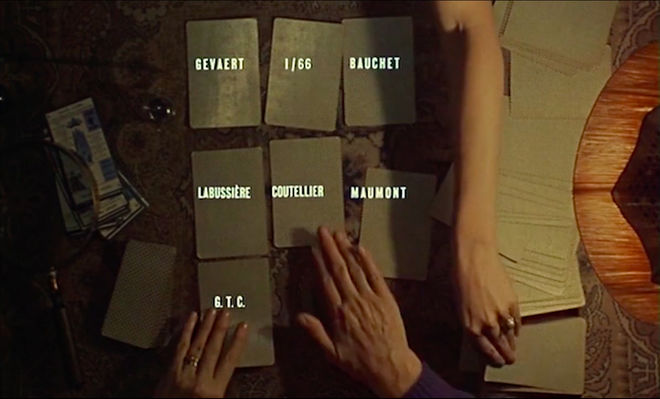

This opening also emphasizes both the iconographic (the colourful tarot cards) as well as the lexical and numerical (the names and times) which highlight Cléo’s desperate grasp for time. The credits appear on the backs of the cards and to the left and right of the screen. The blocky, white typography may look familiar to anyone who’s watched a Wes Anderson film; there’s an official air of breathless announcement when words or numbers appear on the colourful objects on the screen. This effect becomes subdued once the movie moves into black and white as the same white font is used to indicate chapters and the exact time periods.

Varda made the film in the thriving post-war era of modernism, which was quickly overtaking the world. There were virtually no female French filmmakers like Varda then, and indeed, her gender has often been used to set her apart among the French New Wave movement. Her work was seen as a refreshing alternative to the intellectual boys’ club of Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, and other cineastes with a shared obsession with film history and aesthetics. Varda herself marks the contrast between her kind of cinema and the male-dominated group of Cahiers du Cinema filmmakers in a clever short film that Cléo watches with a friend, a parody of Godard’s basic boy-loses-girl premise.

While it’s important to situate Cléo de 5 à 7 and Varda’s work in its proper context – she was aligned with the more leftist, experimental Left Bank group of young French filmmakers of the time like Chris Marker, Alain Resnais, and Marguerite Duras – it’s also vital to look at the film as an individual text, one that still resonates today.

Cléo’s nervousness and agitation within the modern world is not an outdated experience; tools and technology have changed, but the loneliness and emptiness that accompany a frightening ordeal like medical illness, or even its mere insinuation, remain. Cléo is, after all, a pop singer, a woman more rewarded for her blonde beauty than her talents as a chanteuse, so her universe is one heavily predicated on image maintenance. Her preoccupation with death and the brevity of life becomes all the more tragic when the ephemerality of both her youthful beauty and her profession become suddenly apparent during a music rehearsal. “What’s a song? How long can it last?” she cries out in despair. Bubblegum pop loses its flavour very quickly.

Throughout the film, Cléo is resistant to the changes indicated by the Death card, but it ultimately accrues a different meaning for her: that a new beginning is afoot. Her serendipitous encounter with the talkative Antoine, a soldier in the park, is hopeful – his calm and casual chattiness grant Cléo serenity, one that may let her live her life authentically and to its fullest. The fortuneteller, in her way, turns out to be correct.

Director: Agnès Varda

Directors of Photography: Paul Bonis, Alain Levent, Jean Rabier

Editors: Pascale Laverrière, Janine Verneau (as Jeanne Verneau)

Title Designer: uncredited

Music: Michel Legrand