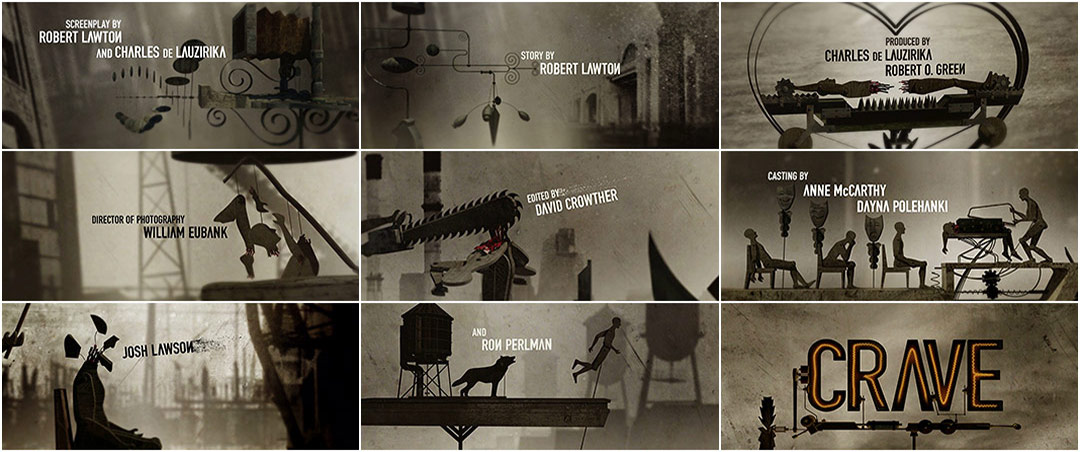

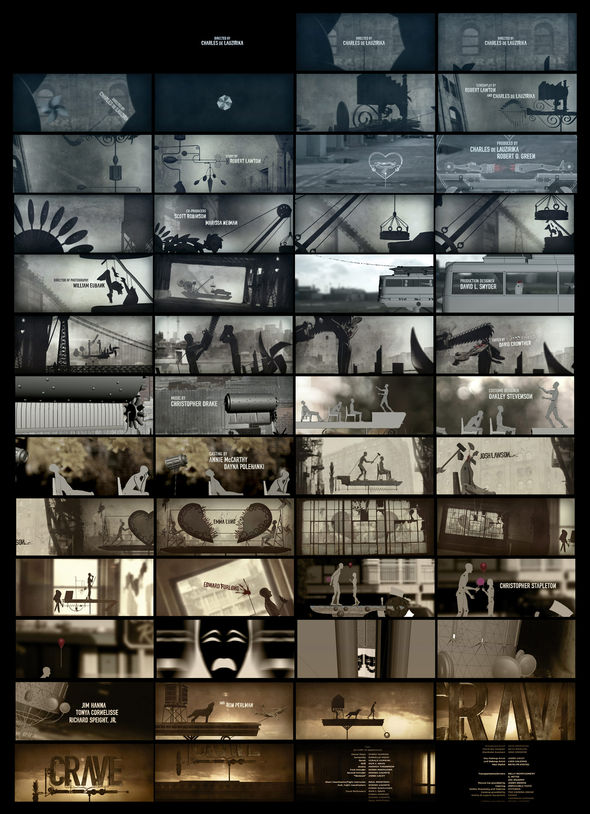

The main-on-end titles for Charles de Lauzirika’s psychological noir Crave take what is at root a basic child’s toy to grim extremes. Wind-driven, humanoid whirligigs are torn apart and re-purposed into disturbing wooden mechanisms acting out vigilante fantasies from the film – images from a nightmare. The angular type stands out from the grit and grain as the camera transitions from grisly scene to grisly scene, each segment part of a larger, interconnected machine which could only be stopped by its own friction.

Director CHARLES DE LAUZIRIKA and main title designer RALEIGH STEWART discuss the creation of the sequence with us.

Can you give us a little background on yourselves?

CL: I was born and raised in LA and I was obsessed with cinema. I went to USC Film School, where I met a lot of great, talented friends, and landed a series of internships and low-level jobs at production companies which got me in the door. The most important relationship to emerge was with Ridley and Tony Scott and their company Scott Free. I started as an intern, became a script reader, then worked on some special projects. I approached Ridley in 1998 to encourage him to get personally involved in the first DVD edition of Alien. He asked if I would supervise it on his behalf! I had no ambition to get into the DVD business, but it seemed exciting and I wanted to make Ridley happy, so I jumped in.

Over the following years, I produced behind-the-scenes content for DVDs and formed my own company, Lauzirika Motion Picture Company. I always wanted to get back to the original plan that my seven-year-old self dreamed up – to be a feature film director – but it’s taken longer than expected. Better late than never!

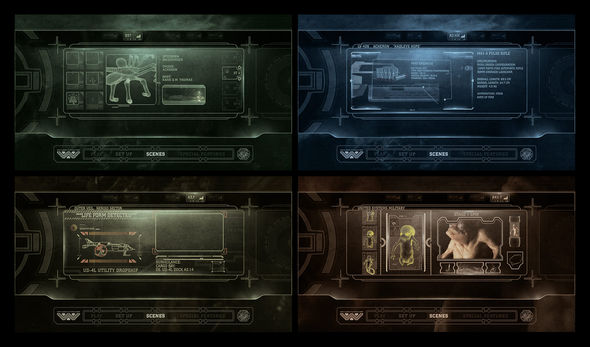

RS: I'm a graphic artist originally from the San Francisco Bay Area. After high school I worked with my father at his architecture firm and it was there that I discovered computer graphics. I landed an internship at a tech company designing user interfaces for DVD authoring software and figured it out as I went. I designed menu graphics for low-budget independent movies and that led to a job in LA where I began designing for higher profile titles. So, over the past 13 years I’ve been lucky enough to work with most of the major Hollywood studios designing menu interfaces, titles, visual effects, and original content for home entertainment, broadcast, and film. These days I primarily focus on visual effects and title design.

Director Charles de Lauzirika on location for Crave

Charles, how did the Crave film project come about?

CL: It’s kind of a long story, but: I’ve been working on a feature adaptation of a Philip K. Dick short story for a few years now with my writing partner Kalen Egan and Isa Dick Hackett, the daughter of Philip K. Dick. While working on this – which I’m still working on – the scope of the project was becoming increasingly ambitious for a first film and Isa suggested I direct something small before we all try to get this futuristic and not-exactly-cheap film off the ground. I scrambled to find something I could make cheaply and quickly. My next-door neighbor at the time, Robert Lawton, had just shown me his ultra-low budget first feature, Sex and Sushi, which impressed me, and I asked Rob if he had anything that we could make on the quick. He pitched me an idea and we spent months in my living room developing it. Eventually we reached a kind of respectful creative impasse, so I bought the script from him and rewrote much of it. Then it was a matter of logistics: finding a window in my DVD schedule, sorting out locations, crew, cast, and so on. That took a couple of years and we started shooting in Detroit in the fall of 2009.

How did you come to work with Raleigh?

CL: We had worked together on a number of DVD and Blu-ray special editions, so I was aware of his design talents and on top of that, he’s just an incredibly sweet, hard-working guy. I think Raleigh had been eyeing the prospect of doing title design for films as a way to get out of just doing DVD menu design. He heard I had made a film, so he asked me if I needed titles.

Alien Anthology menu designs by Raleigh Stewart

RS: Yeah, I'd been working with Charlie for about eight months on the menu and documentary graphics for the Alien Anthology Blu-ray. When I found out he was making his own film, I loved the premise and asked if I could be a part of it – in any capacity. It didn’t matter if I was a dead body in the background or designing the poster, I just wanted to work on the project with him!

CL: As soon as he suggested doing titles, I thought, “Of course! Raleigh would be perfect for this.” So he read the script and we discussed my ideas a bit and then he worked on coming up with looks.

How did you decide to do a title sequence?

CL: I’ve always loved inventive and creative title sequences. As a kid, I loved the titles for Superman, Alien, and the Bond films. I didn’t have such an elaborate sequence in mind for Crave when we began, but I knew it would need to be something that made an impact no matter how big or small it ended up. I went with main-on-ends because I just wanted the audience to be immediately immersed in the film. I think that if you’re going to indulge in an elaborate title sequence – the film equivalent of a curtain call – it should be at the end, assuming we’ve earned it, rather than just shove it down the audience’s throat cold.

RS: We did talk about an elaborate main-on-end sequence that essentially told the whole story of the film, but as things progressed, we narrowed the focus to highlight Aiden’s dark fantasies.

What were your initial concepts for those dark fantasies and how did they progress to the final?

RS: Well, since we knew the foundation was the dream sequences that occur throughout the film, I started designing boards that were very high-contrast and graphic.

CL: They had a very stark noir vibe: black, white, and red. Noir and blood.

Early concept

RS: This direction would’ve worked fine and it looked kind of cool but it didn't really bring anything new to the table. I wanted to do something original and memorable, but more importantly, something that spoke to and supported the story.

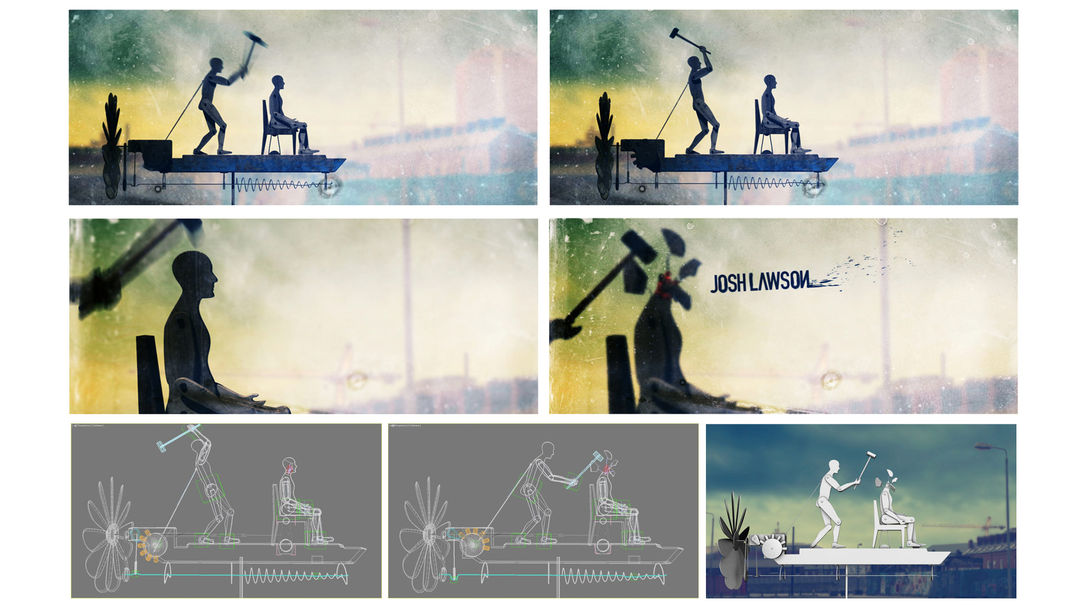

CL: One day Raleigh went off and came back with a completely inspired idea: the whirligig look. Specifically, it was the sledgehammer-to-the-head gag that we use for Josh Lawson’s credit. I instantly thought it was so out-of-the-box and yet so appropriate for the main character’s fractured, cracked prism of a psyche that I just said, “Yes, that’s it!”

“Sledgehammer” pitch process board

"Sledgehammer" pitch animation test

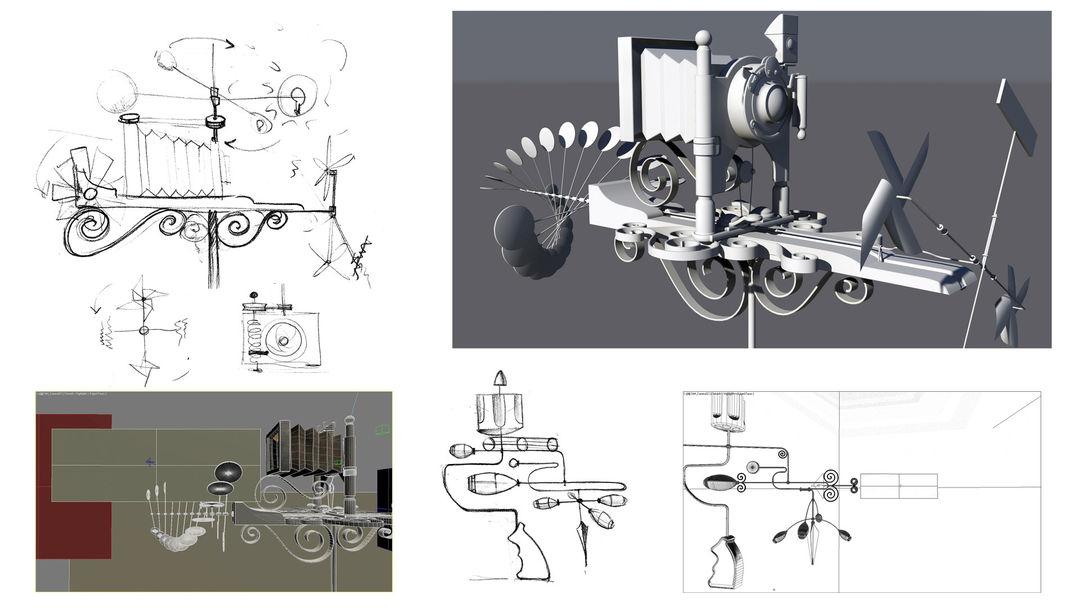

RS: It just hit me like a truck. I remembered that as a kid my folks had these great whirligigs on our deck. The wind would blow the propeller and this rudimentary animation would happen. I was fascinated by how simple and charming they were, so whimsical and kinetic. I thought, "Wouldn't it be cool if we re-created these horrible vigilante fantasies as harmless whirligig scenarios?" I can't remember the last time I saw a whirligig of a man bludgeoning someone with a sledgehammer! I knew it would be an interesting concept but that it’d be a tough sell verbally, so I just started making one. I figured out the mechanics as if I were actually making it in my garage. In a weekend I had modeled, rigged, textured, and animated the sledgehammer scene and Charlie immediately loved it. It was such an unexpected direction but it was really exciting, so we jettisoned the others and got started brainstorming the rest.

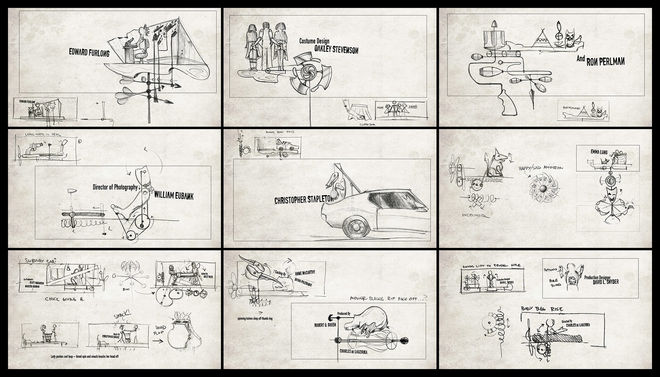

Initial storyboards

CL: The tough part was coming up with a specific whirligig for each of the credits. Sometimes we had to go into deleted scenes and vague references in the dialogue to dig up ideas for them.

So what came next in producing these whirligigs?

RS: I did a ton of research on kinetic sculptures, marionettes, and other wooden devices. I needed to figure out how to get multiple events to happen with the turn of a crank and a way to create delayed loops. For example, in the “sledge-gig” I didn't want the guy to just swing the hammer over and over; I wanted to build up suspense then slam! I also needed to keep the frame visually interesting, leaving enough time for the audience to actually read the titles. I designed trip switches and corkscrews that slowly moved levers and pulleys, triggered the final event, and then reset. I bent some rules here and there, though.

Main-on-End process boards

So after the designs for the whirligigs were approved, you moved into animating?

RS: Yeah. I started modeling, rigging, and animating. I came up with a formula so things would be consistent and I wouldn't get painted into a corner. I then figured out the camera moves and transitions, rendering wireframe animations of each scenario and roughly cutting them together to see how it played. Once the mood and pacing felt good, we paired the whirligigs with the names and transitioned between them. The name order couldn't change so we had to swap, cut, and redesign several of them.

3D model animatics

After that, I added textures and lighting. I needed to keep the typography easily updatable because there was always a chance we might need to add or remove names so I exported the 3D camera data and composited everything. I didn't want to end up with one huge 3D scene where a change to one set-up would affect everything after it.

Main-on-End credits rough assembly

And the main title itself?

RS: Initially, we played with introducing it as its own whirligig so that when you see them in the end they wouldn't be so unfamiliar. I drew inspiration from early Thomas Edison light fixtures because I wanted the type to double as light bulbs. The “A” and “V” in Crave were to light up first, representing the two leads, Aiden and Virginia. In the end it felt forced so we simplified it. Charlie wanted the title suspended in the air and tracking out of frame as the shot dollied over to Aiden. It was a simple concept that ended up being a very striking first image.

Main Title process board

Main Title explorations and final version

You’ve worked with Charlie before. How was your working relationship for this project?

RS: Charlie and I cultivated our friendship while working on the Alien Anthology in 2009. It was impossible to get one past the goalie and I absolutely thrived on that. Charlie is a designer himself, so when it comes to communicating there is a shorthand between us.

CL: Right. And since this production was so ill-planned and since we had so many continuity and practical effects problems in the cut, I asked Raleigh to do a lot of things he’d never really done before, like address several visual effects shots and errors. I had gone out to some of my friends in the visual effects community, but the bids coming back were simply too high. I’m sure they were a deal by industry standards, but our budget was just too tight. Raleigh was eager to give it a shot.

RS: Yeah. I'm always doing little test animations of effects I see in movies or commercials.

When did you start doing that?

RS: I think the turning point for me was in 1999 on The Matrix DVD, listening to John Gaeta talk about bullet time. To me, visual effects are the perfect combination of illusion, problem solving, and design. So when there was an opportunity to do visual effects in Crave, I jumped at it. Charlie showed me a rough cut of the film and pointed out the problem areas. All of the practice and random experiments paid off because before I knew it, a few shots assigned to me turned into over 50! Some shots took a couple hours while others took weeks, ranging from squib hits, carnage, and bodies in the street to background replacements, sign paint-outs, and performance corrections. Each shot was analyzed by Charlie, frame by frame, and there were times I didn't think I could pull it off.

Storyboard, 01/21/11

CL: The work was excellent. I mean, he had never done it before, and here he was knocking out fix after fix, saving the film one shot at a time. I’ve told Raleigh this many times, but he’s on my gold list forever. I just hope he wants to keep working with me!

And how long did everything take from the first meeting to the finished product?

RS: I got the script in August 2009 and immediately started sketching. It was a challenge balancing my fulltime job with the work for Crave but I was so excited about it that I worked nearly every night for the next two years… or so it seemed! The majority of the VFX were finished by late 2011 but we were making tweaks literally a week before the premiere at Fantasia Film Festival in Montreal. It has been a long haul but a really great experience and it has made me a better artist.

And Charles, who or what has inspired you as a filmmaker?

CL: Growing up, I was obsessed with the films of Spielberg, Lucas, Coppola, Donner, and of course, Ridley Scott. It was really Alien and Blade Runner which opened me up to the idea that there was more to science fiction than just special effects and action. These films could be high art too, not just pop art. But in my 20s, I fell hard for the films of Kubrick and the Coen Brothers. Most recently, Refn’s Drive thoroughly rocked my world. If I’d seen Drive before I made Crave, it would’ve been significantly different, I think – more disciplined tonally. Crave is very free-form and mercurial, which is fine because so is its protagonist. But Crave is like a sawed-off shotgun of tone, while Drive is more like a high-powered sniper rifle. I want to make a sniper rifle next time.