The function of a film title sequence is, at its most basic level, to set a mood or tone for the movie in some way. But title sequences can also operate as a filmmaker’s statement of intent. Nowhere is this more true than in the filmography of Canadian director David Cronenberg. If you don’t know what you’re getting into with a Cronenberg movie, you will have some idea by the end of its opening title sequence, whether you like it or not.

The director has described opening titles as “a vestibule before the film”, a time for viewers to pass from their cinema seat into the world of the movie. It’s a beautiful metaphor, and in the anatomical sense the word vestibule – a channel communicating with or opening into another – is quite apt when discussing Cronenberg’s work at large, and his 1988 psychological horror film Dead Ringers in particular.

With Dead Ringers, Cronenberg delivers the troubling tale of identical twin gynecologists Beverly and Elliot Mantle (both impressively played by Jeremy Irons), two halves of a deeply troubled whole. The Mantle brothers are inseparable in work and life, sharing not only careers as world-renowned surgeons, but also – and more troublingly – the many women who enter their lives. Geneviève Bujold plays Claire Niveau, an actress with a rare mutation that fascinates the twins and begins to disrupt the brothers’ cruel balance. Originally titled Twins, Dead Ringers is loosely based on the lives of real-life twin doctors Stewart and Cyril Marcus, who died together under mysterious circumstances in 1975.

Beverly Mantle (Jeremy Irons), Claire Niveau (Geneviève Bujold), and Elliot Mantle (Jeremy Irons)

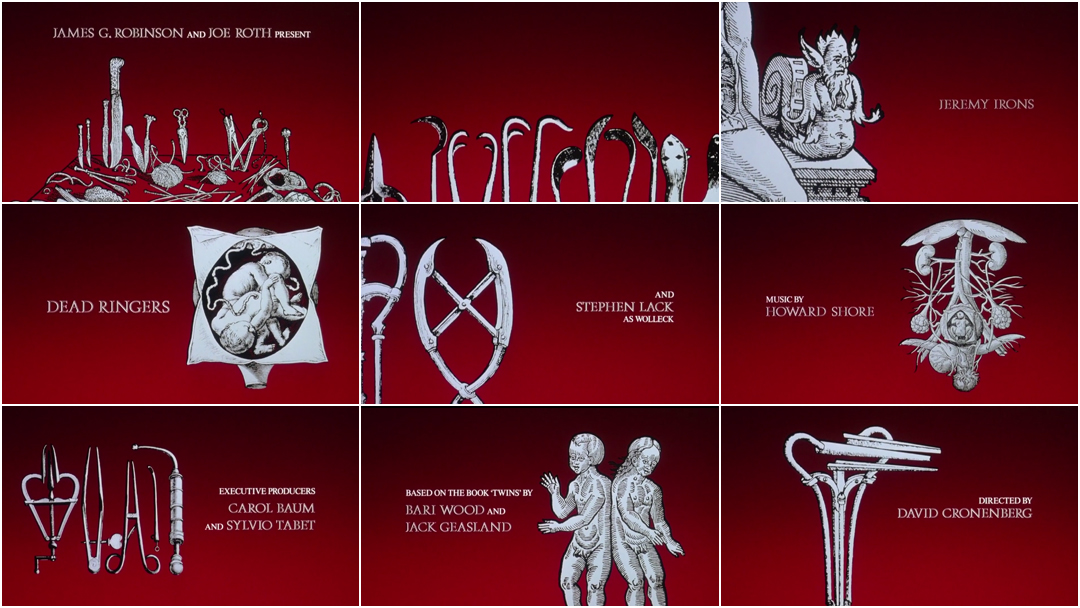

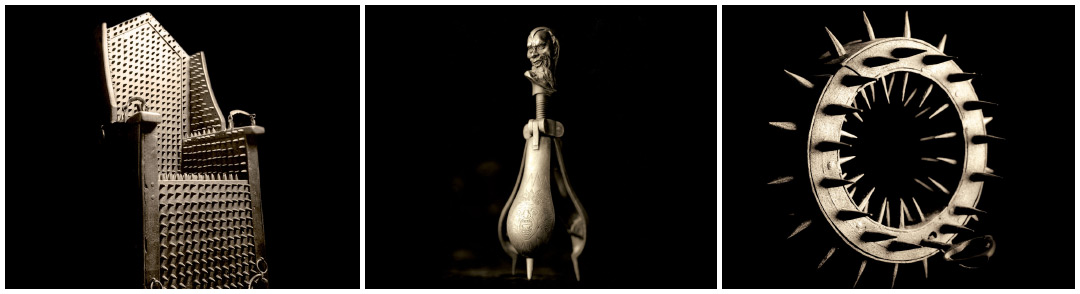

To introduce its disturbing subject matter, Dead Ringers’ opening titles present a moving catalogue of medieval medical instruments, purpose-built, handcrafted objects with a terrible beauty. Are these tools meant to heal or harm? Howard Shore’s refined-but-restrained score guides the camera as it lingers on hand-drawn images of scalpels and specula, hooks and forceps – the tools of medical procedures both past and present – slowly panning across crude sketches of female reproductive organs and twins in utero set against a foreboding scarlet backdrop.

Cronenberg and title designers Randall Balsmeyer and Mimi Everett drew inspiration from the twisted surgical instruments custom-made by the Mantles in the film, as well as an Italian exhibit of medieval torture devices, which both the director and the designers had seen years earlier. Woodcuts and engravings of such appliances, sourced by the design duo from actual Renaissance science texts, provided much of the imagery for the opening.

Balsmeyer & Everett’s contributions to Dead Ringers didn’t end with title design. In fact, the team was originally hired for their visual effects expertise. It was B&E’s groundbreaking motion control camera system that made the film’s incredible “twinning” effects possible. The advanced camera system, when combined with body doubles, optical split-screen effects, and clever editing, allowed Irons to seamlessly perform key scenes opposite himself.

Laying bare the cold brutality of modern medicine and the strange beauty of the instruments that make it possible, the Dead Ringers title sequence is one of Cronenberg’s most iconic and unsettling openings.

A discussion with Title Designer RANDALL BALSMEYER of Big Film Design.

You and your partner at the time, Mimi Everett, worked on three films with David Cronenberg: Dead Ringers, Naked Lunch, and M. Butterfly. How did you first come to work with him?

Randy: So Dead Ringers is actually one of my favourite stories. It was like ’88 or ’89 or so and that started out as a motion control thing. We saw all kinds of work in Variety and I remember seeing the headline “David Cronenberg to Make Twins” and I thought, “Oh, well if he’s making Twins, I’ll bet he’ll use motion control to do the twinning.” And so we just started calling people that we knew had worked on his previous films. David Coatsworth had produced his last two films and so we tracked him down. He said, “Well, you should talk to the DP who’d done his past few movies, Mark Irwin, and pitch him.” He had done all his films up to that point.

Dead Ringers (1988) trailer

So we called Irwin and we found him in like a motel in Louisiana, where he had just shot all night and I woke him up at like eight in the morning. He basically said to do a test because David had used motion control previously for The Fly, but that was a gigantic rig that they shipped out from California on a flatbed truck and it took up like a whole studio. It took like a dozen guys to run it. I pitched him on the idea of a portable motion control that’s light on its feet, that we can carry as luggage on the airplane, and two guys can operate it. You tell us what the shot is and we’ll have it working in 45 minutes.

[laughs] That’s a hell of a pitch.

Randy: [laughs] This was a concept but not a reality. So they said, “OK, we’ll send somebody down to do a test.” We had like two weeks to whip a rig together and we did a little in-camera twinning with it. It was motors bolted to Western dollies and Rockford lights chained down to the top of it – I mean, completely jury-rigged, but it worked! It’s in-camera that counts.

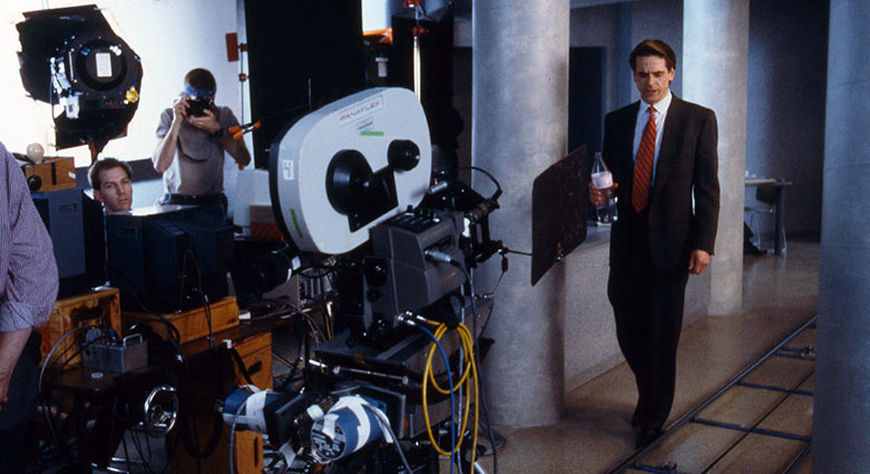

Randall Balsmeyer (L) and Jeremy Irons (R) on set during the filming of Dead Ringers, 1988. Balsmeyer & Everett's finished motion control camera is pictured center. Photo by Attila Dory.

Randy: We sent it to the lab and it came back the next day and it worked perfectly. So they hired us to bring the rig up to Toronto for a few weeks and just be on-call for this period of time that was sort of ripe with potential for twinning.

What was your first impression of Cronenberg?

Randy: He is an astonishing character. Based on his movies I expected a very creepy, twisted kind of character [laughs]. He’s not. He’s like the smartest, funniest guy in the world. It’s almost like he gets his demons out in his movies and that leaves him free to be a very warm and funny and personable human being. And so that was really cool.

David does not like storyboards. He doesn’t like everybody in the world thinking that they know what’s supposed to happen, so his approach is you start the day, you know what scene you’re going to do, you block it out with the DP and the actor and it all flows from there in terms of what the coverage is going to be. It’s a fascinating process.

That’s not ideal for you with the motion control rig, having to program all the moves on the fly, right?

Randy: Yeah. The whole theory behind the rig was that it should be as similar to normal filmmaking for the first unit crew as possible. Rather than us taking over and being programmers, each guy on the crew would do his regular job, with a slightly different gadget in his hands to control it.

For the dolly, we made what we called the speedboat handle for the dolly grip, so it was an upward facing lever that when you push it forward the dolly moves forward and when you pull it back it decelerates. If you want it to go backwards, you pull it back towards you. So likewise the focus puller got a little dial and the camera operator got us a pair of wheels so he could operate it normally.

Randall Balsmeyer and Video Supervisor David Woods review a take during the filming, 1988. Photo by Attila Dory.

Randy: For live-action filmmaking, with actors and everything, it’s much better because everything works just like a regular camera. So your shots come out looking and feeling like the cameraman shot them, because he did. It was really cool. Our challenge was every time we had to set up, it was: “Can we be ready before lighting is ready?”

You were working in close proximity to Jeremy Irons. What was that like?

Randy: I was just telling somebody yesterday – we were talking about how actors control their faces, how they use their bodies as their instrument like a musician would use an instrument. With Jeremy it was the first time I’d been around anybody like that. You could ask him to do anything with his face, his body, timings, and it would happen the next take. He is just so completely in control of that machine that is his instrument. It just blew my mind, I was just astonished.

Dead Ringers' "twinning effect" was achieved using a combination of doubles, split-screen effects, and motion control camerawork.

That’s really amazing. So you were hired to do the motion control twinning, but how did the Dead Ringers title sequence happen?

Randy: So we finished that and principal photography wrapped up. David now knows me as the guy on set with the computer and the tinkertoy camera rig, you know? So a couple of months later I say, “We’d love to do your titles for you.” And he was like, “What? What do you mean, that’s not what you do!” And I said, “No, really, I do titles.” And he said, “Well, I’ll get back to you.”

So he gets back to us and he hires us and the Greenbergs to pitch him. This is our first time going up against the old guard. The first thing we did – and actually this was kind of the secret to it working – was Mimi and I went up to Toronto and just hung out with him for a day to talk about stuff. It turned out that we had this odd thing in common which was that we had both been to an exhibit of medieval torture instruments in Florence.

Image set: Various medieval torture instruments on display at the Museum of Torture in San Gimignano, Italy

Randy: It was probably one of the most… how should I put it? You think you go into a museum and you see racks and iron maidens and stuff like that and it’s going to be kind of a lark. But I got physically sick and had to leave. You suddenly realize that these are real devices that were used on real people and this is horrifying.

David, of course, had seen the same exhibit and was totally excited by it and had a catalogue of it sitting on his desk. That was the thing that clicked between us and so we had the basis of something that related to the film that would be gynecological instruments and the twins.

The "Instruments for Operating on Mutant Women" seen in Dead Ringers were an inspiration for Balsmeyer & Everett's opening title sequence.

Randy: We went up to this medical library on upper Fifth Avenue that has a historical book section and we found all these books from the 1500s about monsters and medical procedures. It was insane. You put on your gloves and they bring out these 16th century books where the paper is crumbling in your hands. It was just so amazing. All of those engravings that we used are from those books.

So you had the concept, what was the next step?

Randy: We put together a sort of art sequence that alternated between twins being considered sort of unnatural monsters in the Dark Ages, as well as images of medical instruments that they had invented back then.

Image set: Original "Twins" concept boards designed by Balsmeyer & Everett

Randy: So, we went up, we did our pitch, and that was it. I don't know whether Greenberg came before or after us – I can't remember now – but bottom line is that David said, "This is great! Let's do it." That was it. So we're all happy and he says, "So, just out of curiosity, did you bring anything else?" We said, “No, no we didn't.” We put all our eggs in one basket.

That was one of our earliest immersions in both sides – in both production and post on the same movie – and it was thrilling. It's hard to be able to do that. Most people like to meet you with one hat on. If you do titles for them, it's titles you'll do for them, and they get uncomfortable when you jump over to the other side for some reason. But he was one who was willing to take the chance, and it paid off nicely.

Let’s also talk a bit about the next project you did with Cronenberg, Naked Lunch. What can you tell us about the production of that title sequence?

Randy: Naked Lunch was a very frustrating project with a happy ending. When you love somebody as much as we love David, when he asks you to do something, you want to come to him with something really huge and elaborate, and we tried.

Naked Lunch (1991) title sequence, designed by Balsmeyer & Everett

What were some of your initial concepts?

Randy: I remember stuff like printing pictures of Eisenhower and the atom bomb on canvas, and making this kind of pop art that had all this history and symbolism in it. We made two or three trips up to Toronto with storyboarded sequences in that general nature, like really content-laden, elaborate texture and style, and each time, he'd kind of go, “Hmm, I'm not feeling it.” We were crushed, you know?

I don't even know where it came from but someone had done a Naked Lunch logo for the crew hats and things like that, which looks like the title of the film. At a certain point, I went, you know what? That's really cool. Let's just run with that and make three shapes and some little abstract lines, let's go the other direction completely. Let's go abstract, no content, no message, no information at all, and just let it be a mood piece. David liked it.

Then it just became a really interesting exercise in colour theory about what do colours do when they combine, which was a very fun testing process.

It’s funny where inspiration can come from! So the sequence was inspired by a logo on the crew hat, but how was it actually shot and assembled?

Randy: The final title sequence was shot on our animation–motion-control camera. The names were all shot onto hi-con black-and-white film. That film was developed and put back into the camera as a bi-pack roll, that would hold out the names while the colour shapes were shot.

The shape art was all black tape and construction paper on clear animation cels, backlit with colour gels underneath. Each colour shape was shot separately, winding the film back in the camera for the overlaps. So two rolls of film passed through the camera simultaneously: the matte roll and the unexposed colour film. The third colours were a result of the shapes “adding” to each other, which we had tested extensively prior to the final shoot. Once the colours were exposed, the matte roll was removed from the camera, and we made another pass to expose the white titles.

I always thought the cool part of this sequence is how the names are only revealed by the presence of the colour panels. It’s like they are there all the time but hiding!

It seemed like a fruitful collaboration between B&E and Cronenberg. Why did you part ways after M. Butterfly?

Randy: Basically David’s got this whole Canadian funding model where every dollar he spends outside of Canada counts against him, and so we couldn't work together anymore.

I haven't talked to him in a long time. I miss him terribly. He just thinks so much about everything, and is so smart and funny about it. He's not doing it to make a buck. Every once in awhile you have a moment where you kind of pinch yourself and go, “This is why I got into this business” and he was certainly one of them.

SUPPLEMENTARY: Randall Balsmeyer and Mimi Everett discuss their title design work in the documentary Movie Title Design (1994).