A blood valentine to the fucking madness, the opening title sequence for Showtime's Dexter is a veritable annunciation of an unholy but likable embodiment of the common rage we can root for. It is a sociopath's ability to focus on the little things.

While stabilizing sources suggest Dexter's episodic beginning was carefully designed, it is also enjoyable to view it as slick Grand Guignol, relatable and savage. Here is a killer consumed by the pursuit of an unattainable satiety, all jaw and maw, whetting this morning-time macabre in florid, ratcheting fashion. With a twisted lick of piano wire/dental floss, a favored mosquito going red, and food gone wild, we are able to refine and contextualize the shape, scream and vision of one Dexter Morgan. The butter of all that blood, shaving to bleed and the tang of hot sauce pyrotechnics, plays toward our tendencies of psychiatrist and sidekick.

In addition to our extensive interview with former Digital Kitchen Creative Director Eric Anderson, we have also collaborated with UK-based film practitioner and film theorist Catalin Brylla who brings to the table a sweeping essay entitled:

Why do we love Dexter Morgan in the Morning?

Why does Dexter's title sequence fascinate us to the point that we watch it repeatedly? How do the shots, the editing and the music contribute to our understanding of Dexter and his world? How does this short sequence prepare us to enter a different reality in which we enjoy a serial killer pursuing the deeds of his secret affects?

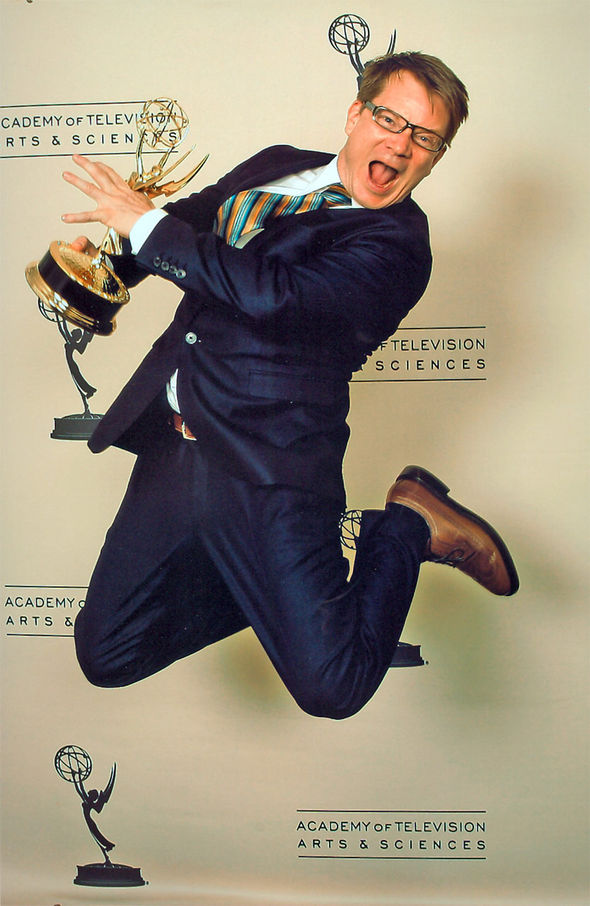

Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Main Title Design

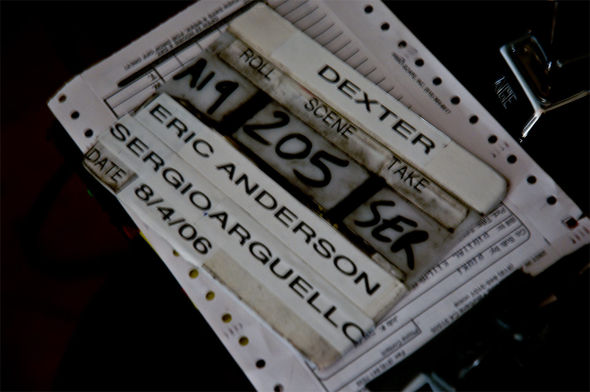

A discussion with Creative Director ERIC ANDERSON.

Tell us a little bit about where you are with your career.

EA: I recently left Digital Kitchen after twelve years, I’m now out on my own. When I joined DK there were just five or six of us above a gym in Seattle, now it's 100+ people with four offices. I started as editor, eventually became a Creative Director, then the Executive Creative Director for the Chicago office. Oversaw tens of millions of dollars of production, countless jobs, bids, pitches and saw dozens of staff come and go. Moving forward I plan to either start a small company, collective or find opportunities to partner with existing entities focused on entertainment and how entertainment can be used for commercial purposes.

Take us through the design process of Dexter from the early concepts, to the development stage and final execution (no pun intended).

I say creative process because I’m not a designer I’m a filmmaker. I think like a filmmaker. It’s been my experience that designers can get caught up in self-indulgent details foregoing larger issues like the piece’s story, how it fundamentally relates to the show, how will this prepare a viewer’s mind for the show, how will it build excitement, anticipation, its overall impact on an audience. This will be the opening scene for the series, an honor above most. To me these issues are everything.

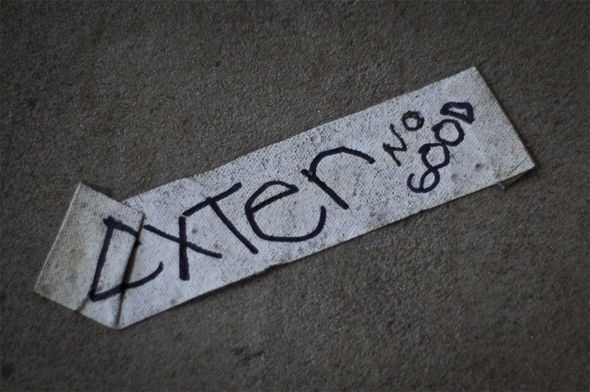

Initial Dexter name experiment

CONCEPTUAL DEVELOPMENT

Paul Mattheaus and I got on the phone with the show creators (Clyde Phillips, Sara Colleton, John Goldwyn and Michael Cuesta) and talked about the character Dexter, his pathology, the overall tone of the show, likes and dislikes, photographers, films, music, composers, Miami, color. I was impressed with how smart they were and wanted to understand their sensibilities as well as needing them to understand ours. I jotted down ideas that occurred to me during this discussion. Immediately, I saw that the letter forms in DEXTER are nearly identical right-side up as they are up-side down, much like DEXTER the character. He doesn’t go through a massive transformation when he becomes the serial killer, he’s exactly the same Dexter except somethings wrong. I really thought that would go somewhere.

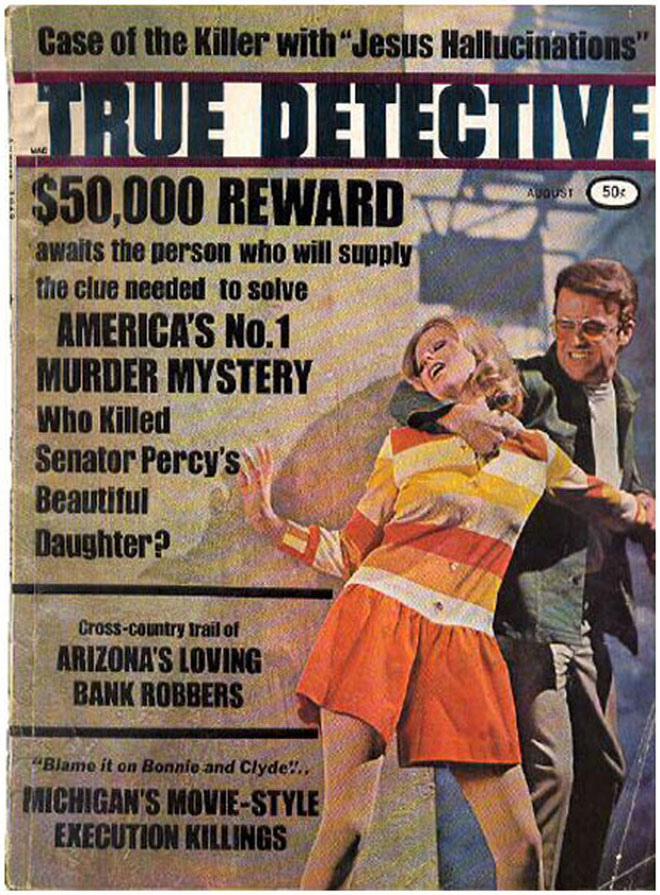

Research and inspiration from True Detective

They kept using the word “mundane” over and over. They liked Six Feet Under and Nip/Tuck for how mundanely both titles dealt with what could have been a visually hyperbolized depiction of each show’s subject matter. This made me think how fascinated I am with crime scene photography, as a kid I loved looking through my grandfather’s True Detective magazine collection. Crime scene photographs contextualize mundane things giving those mundane things overwhelming and sinister importance. Along with this process of photographic evidence gathering comes an edgy anti-aesthetic, factually lit, mundanely framed, rawness. This proved to be a very important point for this piece.

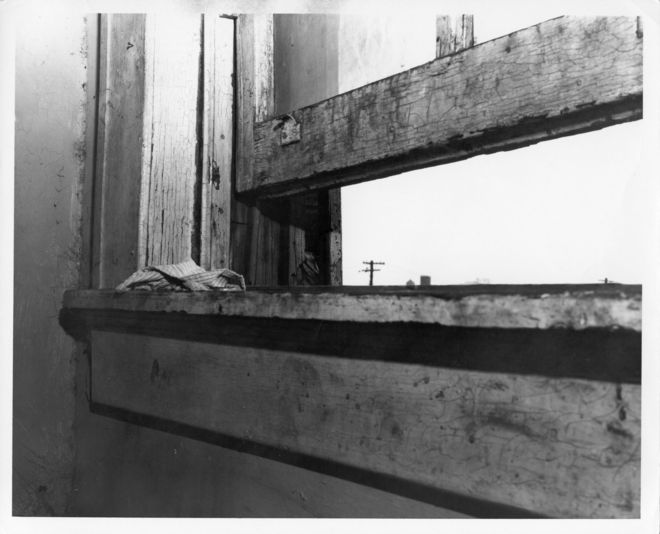

An entire situation unfolds from one photo, this is an ordinary window until you find out that this is the window from which Martin Luther King was shot.

Crime scene photo of James Earl Ray's rooming house bathroom window

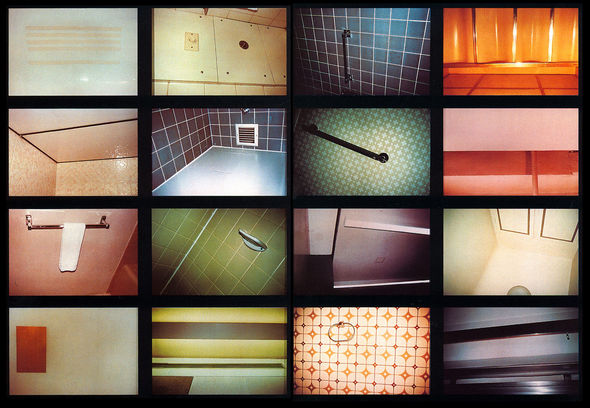

This also got me thinking of two other artists, David Byrne’s book Strange Ritual full of wonderful photos of nothing, and how in the simplest way, Mike Kelley made the cutest most usual things incredibly naughty. Basquait’s paintings came up, but that seemed a little too easy to depict a troubled mind.

Photographs from David Byrne's Strange Ritual

So I assembled a small creative team, myself plus two designers, interpreted the call, presented all my initial ideas and pointed us in a loose direction. After a couple of typical fits and starts, ideas completely off base, entire sequence based on blood splatters, one where everything was upside down like the DEXTER type idea, a dollar store full of murder weapons. I had a designer pursue his personal art work of these elaborate hand drawn collages that mesh together multiple themes, but nothing felt right. We then started examining normal everyday things that could be seen as horrific.

This is when one member of the team, Lindsay Daniels, had the idea of a morning routine. I remember her sheepishly saying “How about him getting ready in the morning?” Bang! That’s it. I believe the original idea was to have him do these normal things violently, but that soon became the idea of recontextualizing normal everyday things in a sinister way, kind of how crime scene photography does as I described earlier.

One image and the write up won us this job.

Stubble close up

Everything, no matter how mundane or beautiful, has an undercurrent of violence to it. It is just a matter of how closely you look. We are conditioned to see a blossoming flower as beautiful. But if you look closely, if you look differently you will see it more like an explosion. Here we see a mundane morning routine illustrated in extreme close-ups showing the underlying tension found in everyday situations making violence a part of everything.

DEVELOPMENT AFTER THE PITCH

One major mistake I made during the development of the piece was to over communicate the idea of crime scene photography. I was referring to how the images would feel, the mundane nature of this anti-aesthetic, how crime scene photography has its own visual language and shooting this in that way will reinforce our concept of mundane yet spectacular. They heard crime scene and thought police tape, blood and guts, dead people etc... the exact opposite of what they originally loved. My screw up, this is where knowing how your clients perceive things is of utmost importance. I was speaking in very abstract terms, they, being writers, were trying to make literal sense of what I was saying. It nearly lost the job right then and there. I was using incredibly loaded narrative language to express my abstract visceral ideas... and for anyone who knows me, trying to make literal sense of ANYTHING I say is fruitless.

Original storyboards

PREPARING FOR THE SHOOT

The show creators had all sorts of things that Dexter would do as part of his morning routine. We created a massive list, I photographed all of the additional things on that list and added them to the storyboard. At one point it got to be five or six pages long, roughly sixty scenes, way too much for the time allotted for the titles. So I shot all of them and assemble them into an animatic. This was helpful for us to decide what should and shouldn’t be shot, as you will see, plenty of scenes in the animatic got dropped. But this was super helpful in coming to agreement on the musical direction which was varying wildly.

It went from a song called “Miami Beach Rhumba” by Xavier Cugat to Lalo Schifrin/Bernard Herman type dark 1960’s jazzy suspense music. I was a big fan of the later so I wanted to demonstrate how well that direction worked my editing the animatic to the theme from “Psycho” by Bernard Herman. Everyone loved the animatic, everyone loved the scenes we settled on, it was greenlit and three days later I was on set in Los Angeles with Michael C. Hall.

Initial animatic

THE ACTUAL SHOOTING

Do you think the budget constraints fueled the creativity?

This was a very ambitious shoot compared to our shooting budget. Being an editor, thinking like an editor, I’m always aware of coverage. On a budget like this it is hard for me to explain why I need two or three angles of the same thing without coming off excessive.

On the shoot the budget constraints helped create the look and the sense of immediacy which is felt in the final piece. This sequence was mostly a tabletop macro shoot, which usually requires a lot of things that we just didn’t have the time for. We decided to work broad, gestural and keep everything simple for a more natural, less commercial look. It has a nice unpolished grittiness. We also took a page from noir lighting on the wides. We didn’t have a budget for set dressing so we just didn’t light what we couldn’t dress. Also, the macro shots gave us an incredibly shallow depth of field (DoF) that helped to keep the sets small but I didn’t realize until I was on set that a 6-8mm DoF would pose a lot of problems. Things kept going in and out of focus simply because our stand-in was breathing.

Only having Michael C. Hall for ten minutes at a time between the scenes he was shooting for the show, so we worked very run-and-gun. I think that spirit ended up on film. The crew along with DP Sergio Arguello and Gaffer Mark Lindsay were phenomenal. And I would be amiss if I didn’t mention the two incredible producers who made this piece happen, Nancy Huddleston the Line Producer and Colin Davis who is a staff producer for DK. Without them I’m just a know-it-all with a hat collection.

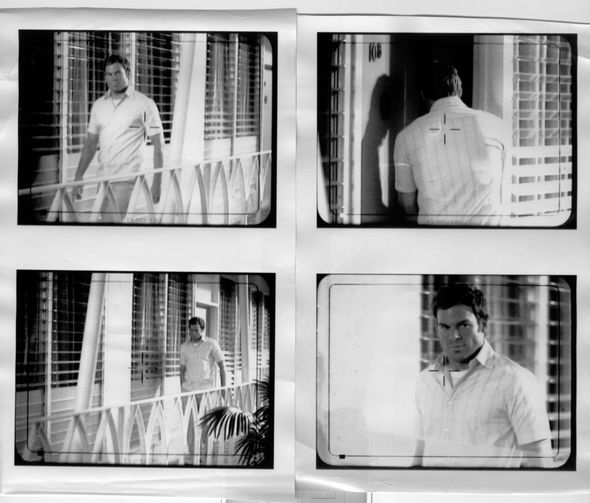

Live-action shoot on set photographs

Did you set goals or is it more of an organic process for you?

My goal is always to make a splash, stand out. Do something special or meaningful, intriguing or something that could inspire someone. Do something that you can put all of yourself into. There’s nothing worse than selling work that needs to be mediocre to exist, and it’s sad to see creative people willing to go there. Something somewhere inspired them to want to make things. The goal is to never forget what that felt like. I remember the first time I ever heard Black Dog by Led Zeppelin, I was ten or eleven years old, and my friend blasted it on his brother’s 901s. I didn’t really know what I was hearing and just stood there dumbfounded. That’s the switch I look to flip with myself when I’m working, ideally.

How critical are you with your ideas?

Well... I try not to even judge the initial flow of ideas, every idea has potential, just get them out on paper and deal with them later. After that I do a lot of research then I let everything sit. Then when I come back to them, I just start abandoning certain ideas because they’re not holding my interest. This process usually results in one or two ideas that I can invest in. I don’t feel bad discarding my own ideas.

When I’m directing live action I’m very critical of what I’m getting on film. I’m not a fix-it-in-post guy. All of my circle takes are two from the final take in a series, I’ll get something great and try two more times to better it, if I can’t I move on. I know exactly what I want and I work very fast, but what it takes to get that circle take can be trying on my producer’s nerves. Then I tend to be incredibly critical of myself when I’m editing. When things aren’t coming together I say to myself, “someone could make this great” so I need to work through that until I impress myself. I typically edit twelve to twenty hours a day.

I have a hard time seeing my work on air. I don’t like being surprised with it, I prefer being the one to hit play. I remember watching the Six Feet Under title sequence on HBO about a month after I edited it, all I was thinking was “oh shit.”

When do you know that something is right?

Intuition. After talking to the clients, most times, I have this gut emotional sense of how the piece needs to feel. I absolutely understand its essence but may not be able to describe it in tangible or actionable terms. At this point conveying this to other people can be like trying to describe a smell from memory. But I internalize and catalogue that sense. As I start my process I go through a series of feelings; irresolute and conflicted, discordant, uneasy, unmoved, uninspired. Then something clicks turning all that dissonance into consonance, things align, I feel present and energized both physically and emotionally. This is the nexus of creativity, discovery, making sense of abstract things and being able to convey their meaning to other people.

Imagine that you’re looking through a box of old photos trying to find one of your childhood friend Pete. You look and look and look, then you suddenly find that photo of Pete and you experience yourself recognizing that photo, that is the feeling of finding the answer. Bringing your ideas to life have a similar cadence. You know what you’re looking for and eventually you experience yourself recognizing it.

Well most of what I do hinges on the feel. Being a musician, something happens inside when I’m playing. It was very common for me to break bass strings because I play so hard and impassioned. I have the same desire when I’m directing, but mostly when I’m editing. I used to sit on a subwoofer so I could not only watch, but feel my edits. On Dexter, I had to edit after hours from 7pm to 7am because the edit suites were booked during the day with other commercial clients. That gave me a good week or two of uninterrupted, solitary editing time. Nothing is more important to me than that. I was by myself, editing incredibly loud, no one was around to distract me, it was late, dark, empty and scary which also comes out in the piece. I slept during the day and edited Dexter all night.

First edit cut to Xploding Plastix's "More Powah to Yah"

How do you view the idea of collaboration after going through this process?

There are a number parts to this answer.

When you develop titles for a serial TV show, you’re at the mercy of the show creators knowledge of the subject matter. All I typically know is what I can extract from one conversation, but the creators have an idea of the trajectory of the entire series, they may even know a thing or two about season two or three. So it’s smart to defer to their better judgement.

Dexter was an incredible experience in how I worked with the show creators on the music. Up until Rolfe Kent’s main title score, the music was wholly undetermined. I had no final direction when I started the edit. I got this Xploding Plastix track from a colleague and I thought it was the perfect piece. I put together a compelling edit, and I thought the sequence was incredibly powerful. The show creators liked it but it wasn’t exactly what they were looking for. Then one day the sent me the Rolfe Kent track. I played it and thought they were insane, I actually flipped out because I was so invested into the track I had been cutting to. But I took a step back and decided to believe in the new music. Then five or six hours into working with it, I totally got it. They were so right and I was incredibly off base. The new track created a push pull with the imagery, it set something grotesque in a completely humorous light. I loved how the instrumentation was loose and cabaret-esque. So I purposely cut the images loose over this new track and a lot of magic happened. They made it better than I was going to.

This was also the first time I had ever tag teamed an edit with another editor. Josh Bodnar, a great friend and colleague of mine, would have probably cut the entire piece but he was booked with clients during the day. So I’d cut after hours and he’d add stuff during the day when he had time. I realized that I wasn’t comfortable with other editors touching “my” timeline, I got a little over protective, and in hindsight wish I would have been more professional with how I handled all that. Sorry Josh. I’m better with that now, but like most creative people, I get so impassioned and wrapped up in my work that something else takes over completely... right now I’m sure every editor I worked with is rolling their eyes!

In-camera photos

So to what degree is your approach to the work clinical and at what point does it become emotional?

It starts out searching for inspiration, that’s emotional, then it’s about conveying an idea, that can be pretty clinical or tactical, how does my idea solve their problem, then there’s putting the pitch together, that can be a combination of tactical, emotional and clinical because it needs to be produceable for a budget. Then there’s pitching which is entirely emotionally guided with good thinking rearing its head. Breaking everything down into a shot list, making production arrangements can get very trying in terms of compromise. Stepping on set, is all tactical until you look at something through the lens, then it's very emotional, and your decisions are guided by intuition. I edit in my head while on set, I know well before anything is even committed to film how it can be cut together, that’s strategic, then everything is in the can. Editing for me is purely emotional, combining images with music is magical. Music and imagery have their own spirit and I pull that out of each other.

What is it to push for something more than the audience is used to? Do you wrestle with taking creative risks? How do you balance and/or meld doing something because it strikes you vs. doing something overtly reflective of the body of the work? When do you hold to a vision and when do your experiment?

I always want to do something identifiable. The phrase “something we’ve never seen before” brings out a lot of creative anxiety, creative over thinking and should never be taken literally. A lot of young creatives try too hard to convince people that they’re creative and end up over complicating everything. The hardest part is doing something interesting yet simple, it’s incredibly hard to show restraint.

Example: David Bowie’s song “Heroes”. Earth shattering on its impact to New Wave music, a mainstream breakthrough when it came out in 1977, but the chord progression is your typical C F B G C that you learned in your first guitar lesson. Nothing new or innovative about it. But if a person was asked to make a song that would create a whole new genre of music, they wouldn’t have ended up with something as simple as Heroes nor would that have influenced a new genre of music. That’s genius.

When I pitch an idea, I do a very good job of making a rational argument for that idea no matter what it is. If I do my job properly, the client should be in agreement with me when I’m done and hopefully it’s identifiable and hits the right pocket in popular culture, that’s all I care about.

What's your favorite part of the process?

I love pitching ideas and feeding off the input I get from clients. I love assembling a team and planting the seed of potential. I love looking through the lens and making shots, love planning the shoot for edit. I love when everything comes together. I love seeing the stuff I shot put to music, and am always energized when all the elements together become something more than the sum of their parts. I love the details in the edit. I will noodle frames on every single edit point, but seeing how two frames change the piece is always a wonderful discovery. It’s like music, playing ahead of the beat or behind the beat, it’s a feel thing.

What brings you the most satisfaction? Seeing the final piece onscreen? Or is it the process that brings you joy. How does that satisfaction manifest itself to you?

I cringe nearly every time I see something I’ve made. I don’t exactly know why. It’s as if I’m letting the general public read love notes I wrote in the 6th grade. I much prefer the process. I love talking about the process of making something, but the end product has me second guessing everything I did or should have done. Standing for something is really hard, too many people in this industry get by by just hating everything as if hating something is an idea. Standing for something is ultimately harder and more courageous. I think when I see my work on screen its that I stood for something and I find that somewhat risky.

Eric Anderson directing the live-action shoot

What can we learn from notable sequences, such as the stylized openings of the Bond series and Hitchcock’s films?

That you need a point of view, and then you need to develop that point of view. Then you have to be known as somebody who has a point of view. Being bold and different will be rewarded eventually. Be aware that there are cowards in the process whose only job is to cast doubt, water things down and pretend that they saved everything from failure. Fear is just indecisiveness manifest in to action. Nothing truly new or different will be accepted initially, that takes courage and probably a bit of time.

What new technologies are you embracing?

I love that you can shoot cinematic imagery on DSLRs and I love that I can edit uncompressed HD on a laptop and I absolutely love Apple’s Pages program, anything that allows me to get my ideas out better, faster and more organized, and I love the internet. The plethora of ways to get messages out into culture is also incredibly intriguing to me, but that’s where it ends. I’m very skeptical of the “newest paradigm shifting technologies” when it comes to work. Responsible for too many gimmicks masquerading as ideas. The conversations revolving around new technologies are typically, “we can do this and this and this” but rarely do I ever hear an actual concept attached to any of these conversations. I’m a strong believer in the basic fundamentals, if those are covered and THEN you have a new device that can make more things achievable, then great. But if all you’re doing is relying on that thing to act like an idea, time will embarrass that piece.

What gets you thinking differently and what excites you outside of design?

Filmmaking, writing, biographies/memoirs, documentaries, essays, personality disorders, silence, being up when everyone else is asleep, working at night, walking, editing, success, attempting cultural relevancy, photography, backroads and small towns, moving to Wisconsin, Ellsworth Kelly, metaphors, being relaxed, John Lautner, Bowie, Eno, Laurie Anderson, music... I honestly believe that music is the god of all arts. By its very nature it achieves what every other art form aspires to.

My source of inspiration is mainly photography from an aesthetic perspective. Music is a heavy influence obviously. I love examining the success of things and hypothesizing on what went into that success. I think that’s why I love reading biographies so much. It’s a road map that great things are possible. Nothing different then the most successful person and anyone else, it’s just that they believed in something inside themselves, worked tirelessly and got a break.

Tell us about the experiences you've had with regard to the presentation you've been giving around the world about this particular sequence.

I don’t spend a lot of time thinking about my accomplishments. I want to get to the next opportunity so I can do something better. But to have 1500 people sit for an hour and be genuinely interested in something I did or what I have to say is incredibly rewarding. More rewarding than winning the Emmys in many ways. Don’t get me wrong, winning an Emmy is great and I’ll never give them back! But it’s professional recognition and that sort of thing is expected, somebody has to win right? The general public doesn’t have to care about anything, and not only that, there’s so much stuff vying for their attention. So when they lock on to something that I made, it’s pretty great, that’s success. To know I had an effect on popular culture is the reason I started making things in the first place. And that’s cooler than any professional opinion.

Eric Anderson deliberately cuts himself shaving

What were some of the most interesting conversations you've had when giving the presentation?

There’s a part of my presentation where I show an outtake of me slashing my throat with a razor. I wanted to get something ‘real’ on film, so Colin and myself slashed our necks as hard as we could to draw blood, but I was dehydrated and he’s bloodless, so it was a wash... but people generally react to that and want to find out if I’m crazy or not. I got in a long conversation with an Irish guy who worked at the Al Jazeera network during the height of their influence, I was trying to find out of he was crazy or not. I met one of the instigators from the Australian TV show “Chasers War on Everything” who dressed up like Osama Bin Laden and attended APEC. I knew he was crazy, batshit crazy, great guy.

And what kind of response to the title sequence have you received to-date?

It’s been a little nuts to be honest. I was recently blown away to have my work on Dexter be included in New York Magazine article on “Televisonaries.” I’m always blown away by the spoofs of the Dexter sequence on Youtube. Some are incredibly witty. It’s interesting to me to meet people completely outside the industry that know the title sequence. I’ll be at parties and be introduced as “the Dexter guy I was telling you about”, hopefully someday they’ll know me as Eric Anderson.

LIKE THIS ARTICLE?