The opening title sequence to Final Approach is that rare beast of film design: mesmerizing in its strangeness, powerful in its effect, and yet familiar in a way that defies reason.

The debut feature from director Eric Steven Stahl, Final Approach is a vital piece of film history that is often overlooked: it’s the world’s first all digital sound motion picture. Stahl, who began his career as an award-winning commercial director, paved the way for digital sound in film with his first short, Digital Dream. With co-writer Gerald Laurence, he designed Final Approach as a sonic showcase, creating the innovative technology for the film and going so far as to make use of 18,000 individual sound effects, many of which were developed from scratch.

The film’s novel use of sound design is evident from its first moments, as that radio crackle comes in, followed by slowly mounting strings. A burst of light suddenly envelops the scene coupled with an eerie voice, a kind of exhalation punctuating the glare. After a smattering of blue sparks, the title card appears on-screen, enormous and featuring the outline of a Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird, the fastest plane ever built. What comes next is an ethereal and electric journey, guided by disconnected voices and static fuzz through space – or is it time? Bits of conversation fade in and away as credits are pushed off and the flashes of light continue, relentless, becoming a hypnotic pulse that pulls the viewer’s curiosity to its outer limits. The effect is much like the one achieved in Wayne Fitzgerald’s opening title design to 1970’s On A Clear Day You Can See Forever, albeit less colourful.

With nods to both Star Wars and 2001: A Space Odyssey, the sequence presents a puzzle of sound and light – an uncanny introduction to a singular film and a world of questions.

A discussion with Director, Producer, and Title Designer ERIC STEVEN STAHL.

Where did you get your start, before embarking on the world's first all-digital sound motion picture?

Eric: So, let's see. I was born in the States but I grew up in Italy as a state department brat. I stayed in Italy through high school and then I decided I wanted to go into communication. My mom was freaking out because I spoke English with an Italian accent. She used to refer to me as being a foreigner. She said I needed a couple of years of American education, so I came back to the States. I enrolled at USC. I was going to the School of Journalism and I was wandering around the campus and I was in front of the old quad which is where the old film school was. I walked in and I'm seeing all these very eccentric filmmaker types with beards and they looked like a bunch of frickin' hippies and I was absolutely mesmerized. I decided to change majors. Then I found out that the film school was the most difficult school to get into at USC.

I figured I would do something so splashy, so high-profile, and Hollywood’s gonna discover me.

Right, it was very competitive.

Eric: I got turned down three times. Every time I would show up they would be like, “You again?” Finally, on the third attempt I got in. But everything was very, very scrappy. They were still using ridiculous reel-to-reel black-and-white video. I thought this was completely lame so I hustled my way to Ikegami and Sony and all these companies and I managed to convince them to sponsor my senior thesis film and I shot the damn thing in colour on quad. I almost got thrown out of the school because they said I broke the rules. I just went out and acted like a producer! It didn't cost me a cent. And that was my first sense of the reality of show business. I really did not want to be some kind of starving artist. In my last year of film school, I was running a little design studio out of my parents' home in my bedroom. My father was dying of cancer at this point, and he said to me, “Obviously you are showing some kind of a predisposition towards design and graphics” and he wanted to help me out. He introduced me to an Italian industrialist that basically became my partner and financed my first business which was a company that specialized in doing entertainment branding. I set up shop in Beverly Hills, at 9100 Wilshire, in a very fancy office. Within almost nine months, I went completely out of business! Burned through all the capital because, at 21, you don't have a frickin' clue about running a business.

[laughs] Humble pie.

Eric: Exactly. And I remembered that when I was in film school, I had approached this company called Glen Glenn Sound.

Glen Glenn Sound was a prolific Hollywood-based audio post-production company which provided creative services to the television and film industry between 1937 and 1986, when the company was acquired by audio post production company Todd-AO.

Glen Glenn, they go back to the days of I Love Lucy and they were doing all the Stephen Bochco shows, like A-Team and Hill Street Blues. They did the sound finishing on my senior project, the one where I had the sponsors. They said they were gonna do a bunch of double-truck ads in the Hollywood Reporter, Daily Variety. I said there's no way that George Lucas or Steven Spielberg is ever going to come to Glen Glenn Sound because of an ad in the trades. That's not how it works! I suggested we develop a proprietary technology and that will give us a wedge in Hollywood. I pitched them on the idea of giving me their advertising budget to essentially launch their new sound center. Glen Glenn just could not get any respect in the feature film world. That's where the big money is made. I said we should do something nobody's ever done in cinema: we should create digital sound for movies.

Is this when you started working on Digital Dream?

Eric: Yes. And that's what Digital Dream was for. Digital Dream was one of the best laid plans of mice and men. I thought this was gonna be my incredible passepartout into Hollywood. I figured I would do something so splashy, so high-profile, and Hollywood's gonna discover me. I was gonna be this 23-year-old genius and the rest would be history.

It seemed that easy, huh? [laughs]

Eric: Yeah, it's so easy, right? So I convinced Glen Glenn to give me the ridiculous advertising budget and use it as seed money. I said, I'm gonna get Kodak and Panavision and Sony and Deluxe Laboratories. I'm gonna get them to underwrite the world's first digital sound film! And they laughed at me. But within three to four months, I had gotten Panavision, Eastman Kodak, and Deluxe to step up. I raised $7.5 million to make the most expensive short film in history and it was shot in 70mm. It took me a year to put it together and that's what Digital Dream was.

SMPTE timecode is a set of cooperating standards to label individual frames of video or film with a timecode defined by the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers in the SMPTE 12M specification.

In those days, the technology was so primitive in terms of sound – digital sound. The only other film that ever attempted it was Fantasia for Disney. And they used this gigantic 3M system which was very primitive. What I did is I got a bunch of Sony 3324 PCM digital recorders – which at the time were like $150,000 to $200,000 a pop – and daisy-chained them together, got a company called Linksys to kind of do this software connection which didn't work for crap that connected to a projector so that using SMPTE timecode, we could play the picture. I mean, this was like doing The Jazz Singer! We were trying to connect sound to picture so that it wouldn't drift. It was a 30-minute film. Visually spectacular, and the sound – obviously nobody had ever heard that. Nobody had ever seen or heard digital sound and picture together.

I raised $7.5 million to make the most expensive short film in history and it was shot in 70mm.

Digital Dream (1983) opening title sequence, directed and designed by Eric Steven Stahl

Eric: We premiered it at Glen Glenn and the strategy was to use that as the linchpin tool to launch Glen Glenn as a serious player in the movie business and the secondary agenda was that Hollywood would see what a genius I was and the rest would be history!

News 4 Los Angeles interview with Eric Steven Stahl about Digital Dream and the future of digital sound

We developed this technology called Digitrack so we were essentially gonna compete with Dolby. Well, here's the joke: instead of getting movie opportunities, everybody and their frickin' uncle came to me about doing brand salvaging work. They said it was unbelievable what I was able to do with Glen Glenn. I took this sleepy old legacy company and made them relevant and cutting-edge. And I was going, “No, no, no. I wanna be a movie director!” And they go, “Movie directors can be hired a dime a dozen.”

I kept on getting pushed back into branding, marketing, graphics. And I ended up landing a piece of Chevrolet business. I did a Clio Award-winning campaign in the mid-’80s called "Yes, It's a Chevy" which was for the relaunch of the Chevy Cavalier on the West Coast. This was an extremely graphical piece of cinema. The whole idea is that when this young woman sees the car for the first time, she's imagining how sexy the Chevy Cavalier is in her brain because it was one of the ugliest cars ever built. The idea was you have these little Hockney synaptic flashes of the car. You never see the car composited together; I deliberately didn't want to show the car together. It was 189 cuts in 60 seconds which, if you consider the technology at the time, was absurd. It was dizzying.

The Clio Award-winning "Yes ... It's a Chevy" commercial (1986), directed by Eric Steven Stahl

Eric: Now, it's like, what's the big deal? But at the time, commercials had jingles and people running through meadows and these long sweeping shots of a car with sun glinting off of it. So all of a sudden I was cemented in advertising. It was driving me nuts!

Compilation of news reports about the "Yes, It's a Chevy" campaign

Eric: But the company grew bigger and bigger and we moved to Century City and eventually I said, “I can't do this anymore. I have to go make a movie.” I looked back and I realized, nobody's picking up the ball on digital sound.

Why do you think nobody had picked it up, even throughout the late ’80s?

Eric: Well, I was kind of naïve. I probably should have patented the development of the technology but I wasn't interested in that. I was interested in launching my movie career. I developed the technology and we had the ability to create a film, record it, and digitally master it and mix it. But there was no way of exhibiting it. I mean, what was the point of having a bunch of digital films that still would have to be released through an old Dolby A playback system in these primitive theaters that were basically vestiges of the ’70s? It was like taking an incredible symphonic recording and playing it through a three-inch car speaker.

You couldn’t disseminate it.

Eric: Nope. But I still saw an opportunity. Which brings us to Final Approach. I regrouped and I wrote this script for Final Approach. I said, “This is going to be the showcasing vehicle for digital sound and I will be known as the guy that did the world's first theatrically digital film and for sure Hollywood now will discover who the hell I am!” Sometimes you set out to do stuff because it's like what Sir Edmund Hillary said. Somebody asked him, why did you climb Mount Everest? And he said, “Because it's there.” You do it because you haven't seen anybody else do it and you just have this desire and drive to do it. We set out to do this and I got Panasonic RAMSA to be, again, a sponsor.

RAMSA, or Research for Advanced Music Sound and Acoustics, is Panasonic's line of super high-quality professional audio equipment.

When I did Final Approach, I combined everything that was my passion: design – which is a huge, huge part of my life and still is – and cinema. I needed to find a vehicle narratively, and a vessel that would be an incredible sonic showcase. I didn't want to make a typical artsy-fartsy film. This film was a mind trip – a game of chess with the brain.

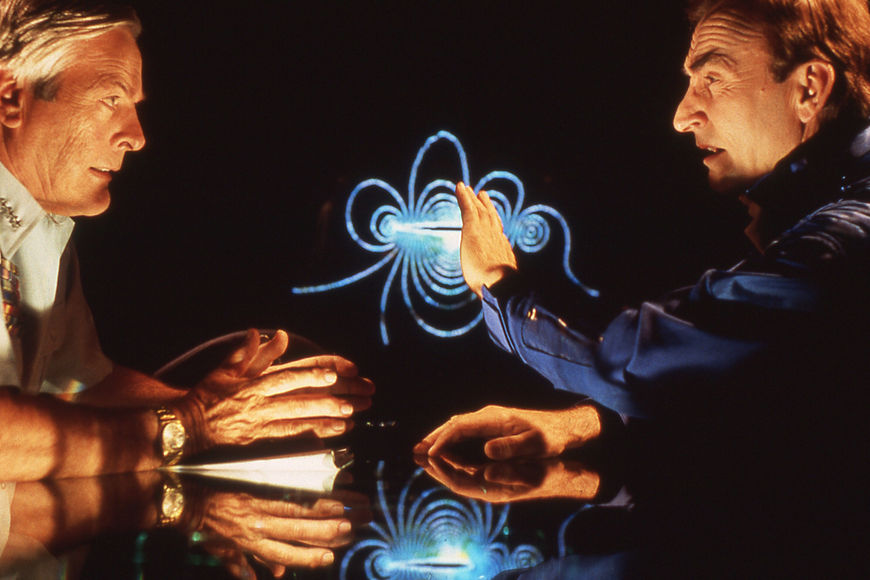

Still from Final Approach: Kevin McCarthy as General Geller and James Sikking as Colonel Jason Halsey

Stunt double wearing an authentic Lockheed SR-71 high-altitude pressure suit during the second unit shoot of the opening ejection sequence while a second AC slates the shot (with the working title of the film, "Blackout")

Eric: Everything that I had learned from Digital Dream and doing commercials and design work was incorporated into that movie. When I finished it, I couldn't get arrested. Nobody was interested in it.

One of the problems of being at the bleeding edge of technology is that you end up getting your face chopped up with razorblades. You're so far ahead of what is considered the accepted cycle of technology. The people that are first to market are not the winners. It's the people that are second or third to market that are brilliant business people that know how to leverage the technology. Being a pioneer is not always such a great thing but somebody's got to do it. I had some very high-level introductions, I had a very fancy attorney, I had meetings with Jeff Katzenberg and Joe Roth, who was running 20th Century Fox, and all these big players. The world's first all-digital sound motion picture. And nobody bought it. Fox almost did. Joe Roth, who had kind of an artistic bent, was almost going to go for it. When he saw the film, he went, “Hmm, this reminds me a lot of Jacob's Ladder.” It was that Tim Robbins movie and there was nothing at all stylistically similar but the conceit was the same. And who knew?! I mean, how do you know that that's gonna happen?!

[laughs] Of all the breaks...

Eric: So it looked like I was left for dead and so I fell back on what I really knew how to do which was marketing. I cut together a trailer and I gave it my all. I took the last few cents I had and I cut the trailer of my life! I said, “If I can't market my own film I might as well hang it up.” The positioning was that it will take you out of this world, inside your mind.

Original trailer for Final Approach (1991)

Eric: I went to Cannes and it became the toast of the town. Everybody fell all over the film. It was bombarded by journalists and media and buyers. It was an insane turn of events. A French company bought the film and it ended up being the second-highest grossing opening movie in the summer of 1991. It was laughable. I came back and Trimark, now Lionsgate, saw an opportunity to make some money off of the film, so they ponied up the money so the film could premiere in the United States at the Cinerama Dome in Los Angeles and at the Ziegfeld in New York, which obviously was a thrill for a kid who had been banging his head against the Hollywood gates.

Final Approach star Hector Elizondo (center, in hat) and Director/Producer Eric Steven Stahl (center) with distribution executives at the film's premiere at the Cinerama Dome in Hollywood, California

Image Set: Promotional signage for screenings of Final Approach at theatres across the United States and in France

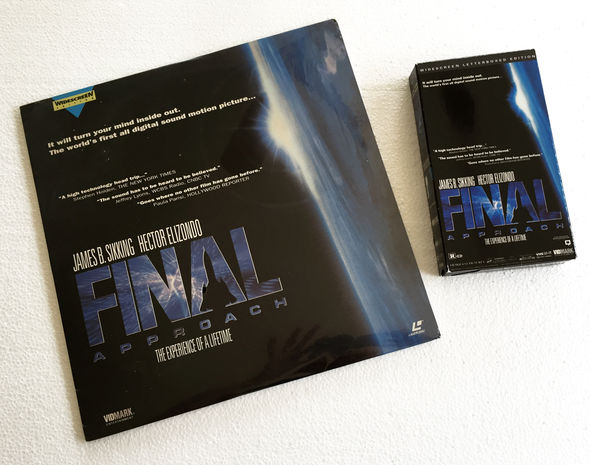

Eric: It opened in about 42 markets and then it went where all movies go, into video-land. It's so funny that the movie’s on YouTube now because somebody obviously pirated a copy of it off of the old LaserDisc and put it on the Internet. This is the bitstream world that we live in. I want to restore the negative and go back to the interpositive and internegative and remaster it into like 4K. I mean, it is the world's first digital sound film!

Exactly. It’s part of film history. It’d be great if Netflix picked it up.

Eric: That would be cool. One of the risks of doing stuff that nobody else has done is that sometimes people don't get it. Or they get it later.

So, some of the influences for Final Approach seem obvious, like 2001, but can you speak to what else you were pulling from, in terms of inspiration?

Eric: I was hugely influenced by Stanley Kubrick, like a lot of filmmakers of my generation, and 2001. When you look at Final Approach it just reeks of 2001 influence. The little particles of light are completely influenced by 2001, the whole star travel sequence. I love the Bauhaus starkness and the beauty and the simplicity of 2001 and so this was my emulation and homage to that.

Excerpt from the Stargate sequence from Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

Eric: The other thing that I was always fascinated with was mindgame movies. I loved Sleuth and I loved The Twilight Zone. Hector Elizondo was the first star that came on board and then I managed to get James Sikking. He had finished Hill Street Blues and right before he started doing Doogie Howser, M.D. The original female lead was Bonnie Bedelia and then at the last moment that fell apart and Madolyn Smith from Urban Cowboy, now known as Madolyn Smith-Osborne, came into the film. Kevin McCarthy was a little joke homage to Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

James B. Sikking, Eric Steven Stahl, and Hector Elizondo

The opening sequence is very unique and strange – even by today’s standards. When you were making the movie, how did you think about introducing the story?

Eric: I wanted to have something that really made people feel like we were inside the human brain. This all ties back to that whole concept in the Chevrolet commercial that I did in the mid-’80s. I developed this kind of Tesla coil; it was this plasma ball that had gigantic electrical charges, it would be zapping electrical charges, and it was developed by a researcher at MIT. I had four of these objects and I figured out how to film them with a Panavision camera.

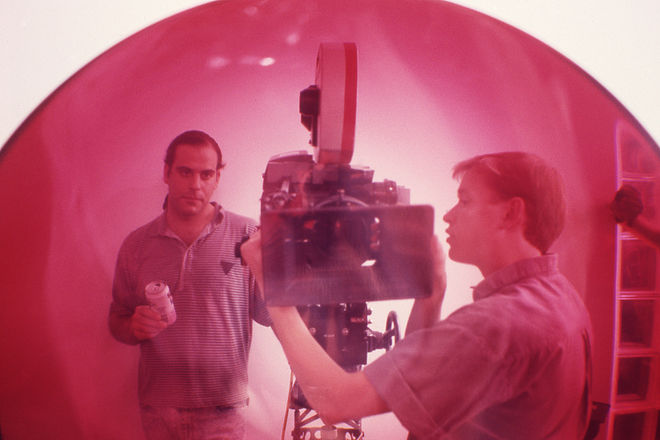

Director of Photography Eric Goldstein with Cameraman Andrew Parke, lining up a shot through a massive six-foot acrylic lens on the main set

Those cameras weigh like fricking 150 pounds but the camera was turned upside-down using a Ubangi overhang so it was like the scaffolding with the camera completely turned at a 90-degree angle, pointing down on this electrical explosion of light. I filmed it at all these different exposure speeds; that was the cornerstone to that Chevrolet commercial which won the Clio for graphics, but this time I shot it in Cinemascope. So I went from little 1.33 TV [ratio] to 2.35 Cinemascope. In the Chevy commercial you have these little synaptic bursts of information and that's what gave me the idea for the title sequence. When you see these gigantic titles flying by, that was also very heavily influenced by Doug Trumbull. You can see that I was using a slit-scan effect which was pioneered by Trumbull and Kubrick in 2001 in the famous Stargate sequence and I combined it with flying through the titles, which was influenced by what I had done with the Chevy campaign. The idea is that all those titles were flying by and we're actually traveling through the human brain and we eventually emerge out of Jim Sikking's eye, who's in the cockpit of this SR-71 reconnaissance super-secret stealth plane.

Final Approach title card featuring the outline of the Lockheed SR-71 in the logotype

I started off by designing the title graphic. All my movies have very strong graphic title sequences. Inside the A is the actual outline of the SR-71 plane. I never use anything that's stock.

I did not have the expertise myself to do the slit-scan stuff so I brought in the folks that did the visual effects on my Chevy commercial.

Are you referring to Jim Funkhauser?

Eric: Oh boy, have you done your research! Yeah, Jim was the guy who did my visual effects on the Chevy commercials. Susan Shankin was the artist that physically took my design sketch and executed the final camera-ready art. And then there was someone who physically did the animation work. In those days, everything was done with animation cels. We took an Oxberry animation crane and the way a slit-scan works is you have the crane go up and down and the film moves in incremental moves and so in the animation cel, you can take little pieces of coloured gel and – depending on how you arrange it and how you backlight it and depending upon how the camera travels back and forth on its axis – it creates a streak. Every time you open your exposure – you're obviously in a dark room, in an animation crane room – you backlight this cut-out piece of film with a slit of coloured gel and the camera would go all the way down and then go all the way back up. That's why it's called “slit-scan.” It creates a perspective streak, and then the film moves another frame and you slightly change the distances. The distances get bigger or smaller and that gives the illusion of movement. And you do multiple passes.

An Oxberry animation stand is a type of rostrum animation camera stand used in photoanimation.

Cinema Research Corp. took all our elements and basically folded them together. They would turn all the stuff into interpositive film. So they would shoot the negative, convert it into an interpositive, and then they would stack, in perfect registration, these multiple elements. One of the elements they shot was the plasma sphere, then the stuff that Jim Funkhauser had done was added – the technical slit-scan – with all these little streaks of light and bursts that are moving by you that give this sense of three-dimensional perspective which was obviously key to creating that whole digital sound experience. Literally you hear the sound wrapping around your brain so you're like immersed in this voyage. Then the final element was taking the outline of the text of “Final Approach.” It was essentially a reversed-out negative so that there was a window that was clear and the camera would literally travel all the way into the airplane of the word “Final” and back so you have the illusion that the word “Final” was flying towards you. It was all photo-mechanical. There was nothing electronic except for the computer that controlled the animation rig. It was hours and hours of the camera going up and down.

How did you develop and design the sound? The sound is the reason the film exists, and it’s such a huge part of the film.

Eric: Final Approach was absolutely a sonic showcase. I've always viewed sound as an absolute 50/50 partner. A movie without sound is like a radio show backwards. Meaning, if you have sound and no picture, or if you have picture with no sound, you don't have a movie. You can't create that illusion because it's all magic. Right? Movies are magic. That's all this is. It's all about creating the suspension of disbelief. The sound creates that final suspension. To me, the test of a great movie is when I'm not even conscious that I'm in a movie theater or that I'm watching it on Netflix or HBO. I'm so transported that I'm not thinking about watching something. The whole idea is to have people hear and see stuff that they think is familiar but that they've never heard before.

Ken Teaney (right), lead re-recording mixer, works at a soundboard at EFX Sound Studios in Burbank, California during pre-dubs for Final Approach

Eric: While I was writing the screenplay with Gerald Laurence – the other writer that worked with me on the film – the strategy was, how do we create situations that lend themselves perfectly for this kind of psychoacoustic experience? How do I create an experience that conceptually is built around the notion of sound? As opposed to writing a script and sound being an afterthought where you turn it over to a post-production team, we literally conceived the screenplay from the ground up around sound. What kind of a framework can we use to create this sensory aural experience? That's how that was designed. The script described what was happening sonically.

We literally conceived the screenplay from the ground up around sound.

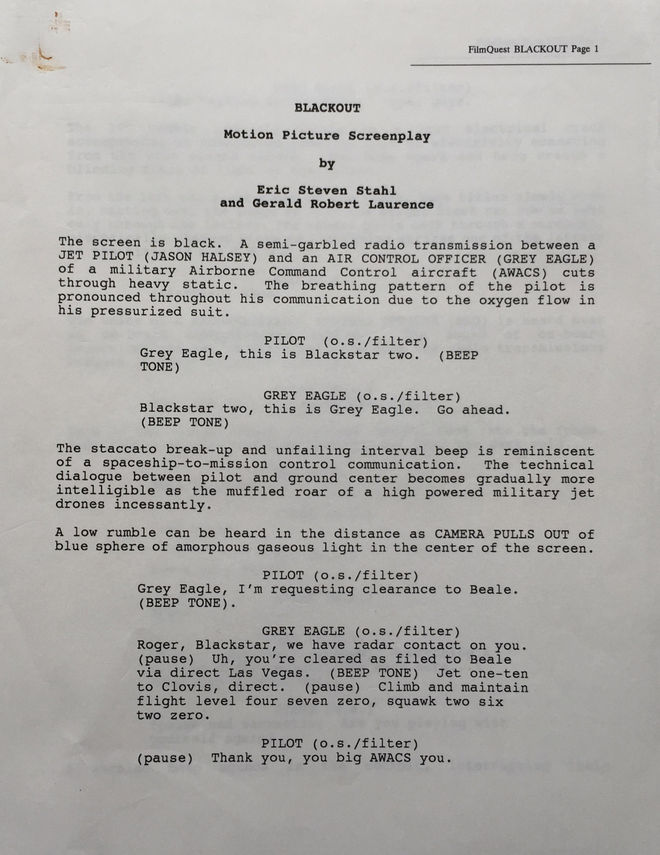

Image Set: Two versions of the Final Approach screenplay detailing the film's opening title sequence. In the first version, the working title of the film was "Blackout"

Eric: And I think the whole conception around sound design was that it was really the third character. The three main characters would have been Hector Elizondo, Jim Sikking, and the sound – and then everybody else.

For example, there are these flashbacks. There’s the voice, which is my voice, and the other composer's voice was going ah, ah, ah...

That was your voice?

Eric: Yes.

Amazing. [laughs]

Eric: Yeah.

It’s fantastic how the title sequence isn't just its own entity – it’s an introduction to a recurring element. Those sequences repeat over and over within the entire film.

Eric: Right.

So it's establishing this kind of visual and aural language that the main character's trying to decipher throughout the entire duration.

Eric: Yeah, because he doesn't get what’s happened. And so Hector Elizondo's character is trying to give all these clues. I was inspired by what happens when people have seizures. It's interesting how your whole life gets influenced. My father died in 1980 and he had cancer and it eventually spread to his brain. I remember that after they had done radiation treatment on his brain, he had a horrendous seizure. That moment of seeing him writhing on the floor left such an impression on me. To see your father writhing on the floor and my brother's trying to jam a spoon in his mouth because in those idiotic days, they said don't let him choke on his tongue, which obviously now we know is like no, just stand clear of him and don't do that. And he broke [my father’s] front teeth trying to jam this spoon into his mouth.

Hector Elizondo looks down at James B. Sikking in this still from the seizure scene in Final Approach

Oh! But notably, they don't do that in the movie. They clear the floor and wait during the seizure.

Eric: Yes! [laughs] Because I learned that. You’re not supposed to do that. They won't swallow their tongue. You can see how real life stuff colours and affects the narrative fiber of your creative work and sometimes it’s conscious and sometimes it’s not. I have not thought of that connection since 1989. This conversation I'm having with you – it's not ever even dawned on me. That linkage between Jim Sikking writhing around was influenced by seeing my father writhe around… that the whole fascination of what happens in the brain and those flashbacks. The whole Rorschach test and those flashback things – and I know this sounds really weird and creepy and you probably don't wanna put it in a piece – but I was seeing my father writhing around and I couldn't help myself, going, “I wonder what the hell's happening in there? I wonder what's going through his head? Is he feeling anything? Is he seeing anything?” And so this was my artistic interpretation of this character's flashback seizures which obviously was a narrative device to help him reconstitute his life.

And what about Apogee Productions? They’re also listed in the credits. How did you work with them?

Eric: Yeah, so Apogee, you’ve of course heard of John Dykstra who was a two-time Academy Award-winning visual effects guy? Well, he and I go back. Scary to admit this! I was truly a child and he was a young man when I met him on Digital Dream. He was my visual effects supervisor and he was running a company called Apogee, and – hold onto your underwear – Apogee is basically ILM. John Dykstra started ILM for George Lucas to do Star Wars. They started their shop on a little street called Valjean that's about five miles from where I am now which is right on top of the Van Nuys Airport. I approached John when I was doing Digital Dream. And he was wonderful, very helpful. Apogee lent their services on Digital Dream and that's where I established my relationship with him. Years later when I did Final Approach I went back and I said, “This is my first feature film. Do you want to help me out?” And so they did an enormous amount of the visual effects work and compositing work. They had their own optical printing system just like Cinema Research and did an enormous amount of work on Final Approach. He's the guy that came up with the idea in Final Approach where the camera – at the end of the title sequence – pulls out of Jim Sikking’s eye. That's all John Dykstra.

He came up with the idea of creating this gigantic white shell using a VistaVision Butterfly camera which was what they used on Star Wars. He, myself, and a guy by the name of Matt Black took a Learjet and flew over Lake Powell at a very low altitude and photographed, in VistaVision – this 8-perf camera, all the plate shots – flying, like a cruise missile point of view over the ground. Apogee was very well known for having developed that technique because they did it for a Clint Eastwood film called Firefox. John still had all the rigging developed for Firefox. We used that same technique, the same rigs, the same set material. And that's how we got that Monument Valley–Lake Powell flyover.

Final Approach second unit crew films a dawn sequence on location in Monument Valley, Arizona

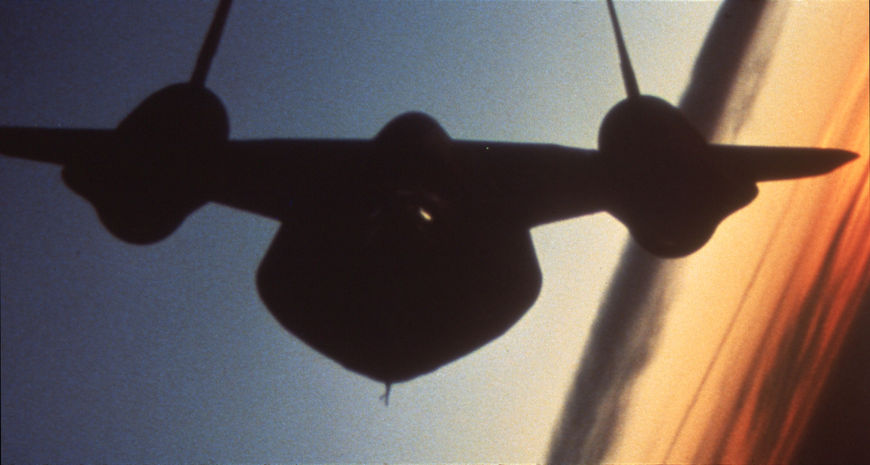

The film's centerpiece aircraft – the Lockheed SR-71 – flying above the desert at sunset

The world’s fastest aircraft – Lockheed’s famous SR-71 high altitude spy plane – preparing for a night run at its home base hangar, at the 9th Reconnaissance Wing at Beale Air Force Base located approximately 8 miles east of Marysville, California

Director Eric Steven Stahl lines up a shot with Director of Photography George Stephenson high in the mountains of Monument Valley, Arizona

Wow. While you were working on this, you were treading uncharted territory in terms of technology, and also personally. Your first feature film. What was the biggest surprise or the biggest challenge for you?

Eric: Everything.

Every single thing, because it was all brand new?

Eric: Everything, you know. The upside is you get to go where nobody has gone before. The downside is that sometimes there's a reason for that. We encountered an enormous amount of failure and problems. The first several tries were a mess. For example, in the first passages we had huge exposure bracketing problems. Then we didn't have that kind of fluid motion that we wanted or the illusion of being able to fly through the titles, which was key to the effect I was trying to create. It looked clunky. It wasn't as smooth. There was no previsualization in those days. I think a lot of the problems we were encountering was that nobody had ever really done what we did. I remember studying Richard Donner’s title sequence in Superman.

Right, that was designed by the Greenberg brothers.

Eric: Yes. R/Greenberg, which were absolutely the bomb at the time. I remember carefully studying what they did. They started their shop when I started my business, but they were in New York. They were really the Rolls Royce in terms of title design work. If you saw the title sequence for Superman at the time, it was insane. I still remember seeing it at the Chinese Theater in Hollywood on a big screen with that sound. It was just like, “Wow, this is the movies.” That's kind of what we were aiming to accomplish.

Superman (1978) main titles, designed by Steve Frankfurt Communications / R/Greenberg Associates, Inc.

When you look back on Final Approach and that title sequence now, almost 25 years later, what does it bring about for you?

Eric: Well, the most interesting thing is once in awhile I will get an email out of the blue, like yours. I don't know how you guys discovered this. Who brought your attention to us?

Well, we often ask designers what their influences are and what their favourite sequences are – which I will ask you in a few minutes – and we asked an Ontario-based designer and he mentioned Final Approach. We tracked it down, and then we had to talk to you.

Eric: Wow. It's nice to know that when a tree falls in the forest somebody's there to hear it because this can be a very lonely and tough business. It makes you feel that you've done something that has influenced and potentially contributed to other people's lives the way somebody else's artistic work has influenced and contributed to what you've done. And so the baton gets passed on. That's a very cool feeling, especially after so many years. You know, that was kind of the beginning of my career. I think in terms of technical slickness, I haven't really changed. My focus used to be more on cinematic spectacle, but as you grow older you get more into character and life. I guess as you start facing your own mortality your priorities and your interests start shifting and – not that I wouldn't love to do a really slick sci-fi movie – but I’ve found myself driving more in the direction of character and relationship stuff.

Final Approach LaserDisc and VHS tape

So when you ask me, when I put a lens of a quarter of a century, which is kind of a scary thought, [laughs] and you say, what kind of memories do you have of that experience? The truth of the matter is the biggest challenges are raising money and getting the film sold and seen. Those are really the biggest challenges. As difficult as it is to physically make the film, in relative terms that's a cakewalk. It's almost like you're feeding a drug habit. You know, it's like you're willing to go to the end of the Earth and dig ditches just so that you can have that moment where you could have this flower blossom. So, it's kind of cool when you see somebody online go, “Oh my god.” It’s nice to know that it just hasn't disappeared into oblivion. That's a cool feeling.

Final Approach was absolutely the bleeding state of the art. And now you look back at it and you go, “Oh, it's so quaint.” With the exception of the sound; I think the sound has been able to stand the test of time. It's like looking at a fine handcrafted automobile from the 1940s. You admire the craftsmanship but it's not a modern vehicle, obviously.

You've mentioned 2001 and Superman and their influence. I wanted to ask a little closely about that, from a design perspective. What would you say are some of your favourite title sequences?

Eric: This is going to totally throw you. I love the title sequence to City Slickers. It was this ridiculous… Remember the little animated thing with the lasso? It seems so not me because if you looked at the body of my work, everything I do is so slick and polished and calculated and geometric and yet at the end of the day, there was a joke. You have to look at it in the context of the project.

City Slickers (1991) main titles, designed by Wayne Fitzgerald and animated by Kurtz & Friends

Eric: It's kind of a lost art. I love that you guys are doing this. The days of truly brilliant titles, of Saul Bass, Maurice Binder, all the classic James Bond stuff. It is such a fantastic craft. I mean, even for TV now once in awhile you'll see great stuff. There's a Netflix series called Marco Polo. Oh my god, unbelievable. You just go, “Wow! That's why I'm in this business!” You just look at it like, that's movies. It's that feeling. It captures that initial innocence.

It's the overture. It's the time to get you warmed up as opposed to slamming into the film, so I very much miss that because I find that's what made those James Bond movies so delicious. It telegraphed or set up the kind of experience you're going to have in the movie. I'll never do a film that won't have an opening title sequence. I mean it just makes no sense to me.

LIKE THIS SITE?