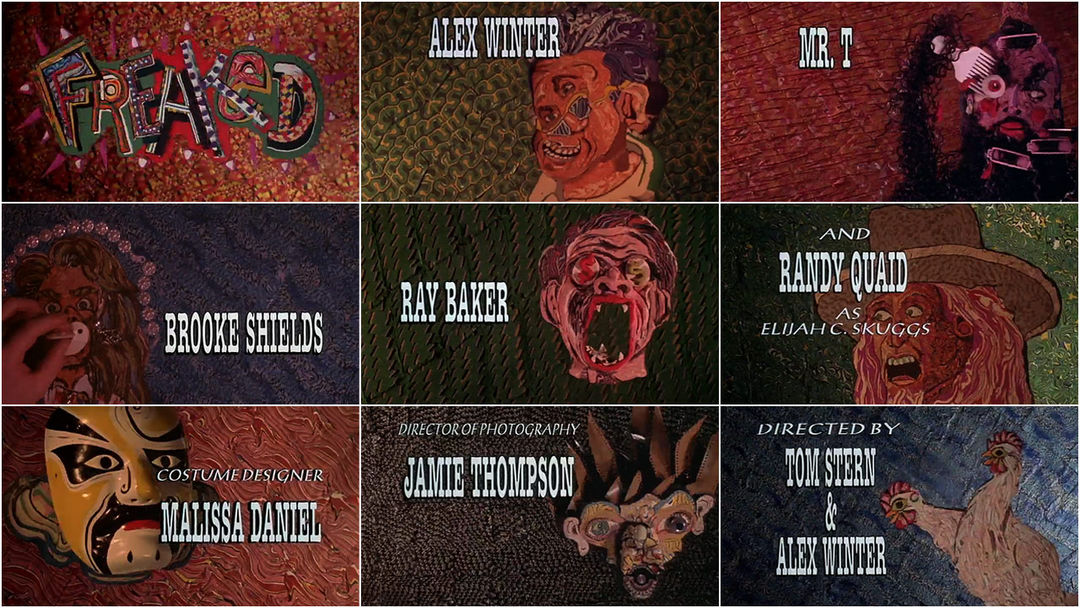

The psychobilly opening to Tom Stern & Alex Winter’s Freaked is strung on the brute wattage of the Henry Rollins/Blind Idiot God track and the unfettered fury of one Mr. David Daniels. The creator of modern stratacut animation, Daniels has essentially refined a process where the image – and the movement of the image – is molded into clay. Take a moment to think about that.

The shape of the clay resembles a loaf of bread. A knife is used to slice one end of the loaf and a camera captures that image as a frame. Another slice, another frame. Put those frames together and, like a flip book or film projection, motion results. Here, the shape distortions of Daniels’ motion sculpture smear like some extended night terror, some piranha at your neck.

Stepping through each frame reveals either kohl darkness or something on fire; Möbius stripped earlobes filling their ear holes like snakes, etc.

But how to understand the geometry of the movement within the clay? The varieties of movement and control in this construct require a dialog with its creator, David Daniels.

His new website on how to create stratacut is a must see for fans of this type of animation.

A discussion with main title director DAVID DANIELS.

How did you first become involved with developing stratacut?

DD: I had this thing called Clay Town… I grew up in a family of four and I’m the youngest. We had a Sir Walter Raleigh coffee can left over from ancestors, perhaps grandparents, and it had clay in it. Mom set us up at the kitchen table and we started play-sculpting. I was five years old when we started this and we never put it away. For many hours each day, Clay Town consumed the kitchen table. We did this from the age of five all the way through high school.

My older sister would enact marriages and soap operas – someone cheating on someone else with little blobs of plasticine – while my other sister, Shelly, would sculpt and she was very good. Incidentally, she later sculpted Jack Skellington for the film The Nightmare Before Christmas and some of the early work at Pixar, like Toy Story.

Anyway, what led to stratacut took place around the age of seven. It was a birthday party and we made a cake out of yellow and blue clay. We cut the cake and I looked at the pieces and thought, “Okay, it’s all there. It’s quite beautiful and quite clean and I’m going to do something with that one day.

Were you animating anything at this age?

It was all sculpture at this point. That is part of the reason I got into filmmaking. Clay absorbs any kind of dirt or lint or punctures or any kind of rough treatment. The plasticine gets very dirty and doesn’t last. So I have all these really neat clay sculptures but cannot show it to anybody because by the time it has been put into a presentation it has gotten dusty and limp and a little funky.

Stratacut is a sort of reinvention of that sculpture because when you slice it open you get a clean slice so you are always revealing something fresh and, in a sense, undamaged. I began to animate and that led me to filmmaking and filmmaking led to storytelling and storytelling has led me to shooting live-action and mixed media.

I did my first animation at the age of 13 and won an award called Cine Media Five which was put out by Kodak and the Broadway department stores. They brought me to New York and put me in the Plaza Hotel and gave me a thousand bucks – that was the beginning of the addiction! I thought, “Hey! This is the lifestyle I’m going to want to live someday, so I’m going to keep making these movies.”

The how-to stratacut animation video is fascinating. Do you have a series of these videos for your work?

There is no creative behind-the-scenes for each one. The video you have was done in either 1992 or ’93. I do have ten hours of extensive how-to footage I did in 2000 from a stratacut class I held at my studio for people who were interested. I went over every trick or technique or approach and tried to show whatever I had learned and developed and was worth passing on. It’s all digitized now and I keep swearing I’ll edit it down to 90 minutes.

I left the stratacut story at age eight and picked it up at age twenty-two. And I did nothing with it between that time. I worked in traditional animation and stop motion and filmmaking at San Francisco State. After I graduated, I had a summer off and it was an unusual summer in that I didn’t have any real obligations. I met a girl who had an apartment and was away most of the time and I was able to try to figure out how stratacut works. I sat and cut everything I could think of in every direction in a very reverse-engineering kind of way and calculated the ways the image would animate. It was a lot of, “If you put a series of sliced frames together and twisted it in this direction then this is the result.” After a while you realize it is basically motion sculpture. Stratacut is the technique but what you are really doing is sculpting time. You are creating these blobby, spaghetti extrusions with a lot of distortions in them. You are calculating how they will be revealed in time. The potential energy that has been sculpted into them is revealed as kinetic energy once it is cut apart. So I tried to figure out all the possible geometric principles on which the twisting of the shapes would yield the ideal result – the blinking eyes, rotating faces, walking, etc.

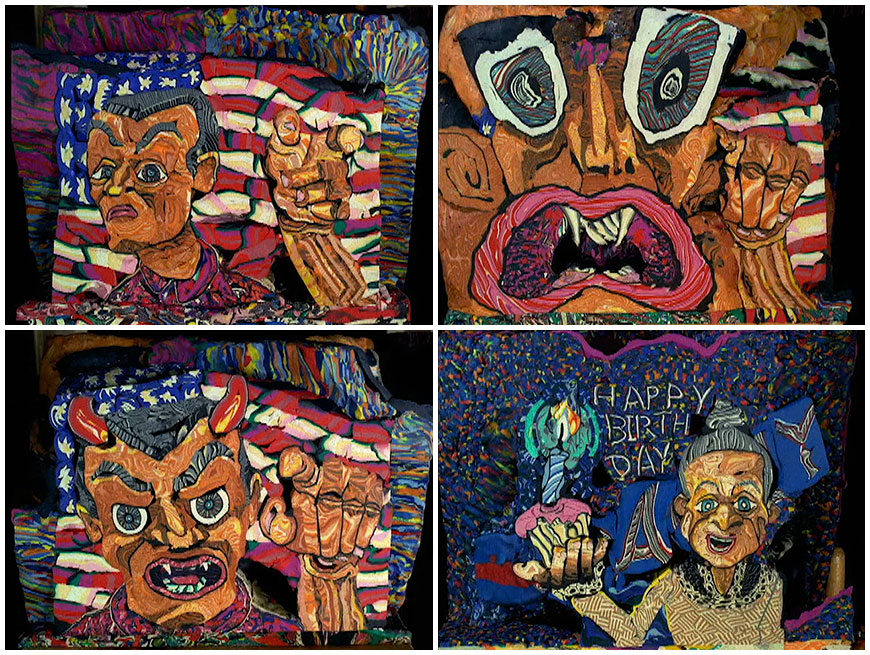

Buzz Box thesis project

I then went to California Institute of the Arts for my masters. My thesis project was the visual onslaught of Buzz Box, where I sort of took television through the sieve of stratacut and tried to regurgitate it so that hopefully people could see their own over-consumption anew as if you were viewing alien broadcasts through stratacut and it showed you 100 hours of TV jammed into fifteen minutes. That was Buzz Box. It was trying to force an audience to face overload in a structuralist film as a way to come to grips with it. I was trying to seduce and abuse them at the same time. It was very hypnotic and very sensual but also aggressive and angry because it is trying to keep your attention at all costs. To me, television and cinema do that – they give you a little bit of story and then jam advertising or the excitement of bullets and guns at you – anything that can grab your attention in a visceral way.

I ended up in New York on Pee Wee’s Playhouse. The director, Stephen R. Johnson, also did a Peter Gabriel rock video, “Big Time.” He had seen Buzz Box, my student film. It got passed around a lot. I was told it was circulated around the UCLA dorms on a VHS dub from ¾ inch tape as some underground let’s-smoke-pot kind of evening of entertainment.

And how did you become involved with Freaked?

Alex Winter was an associate of Tom Stern who also had a show on MTV at the time, named Idiot Box. John Payson at MTV was in charge of a lot of interstitial material and had hired me for a number of projects including Idiot Box.

The crew from Freaked had $18,000 in the budget for the title sequence and about three weeks. The primary animators were Michael O’Donnell, Galen Beals, and myself. Michael and Galen sous chef for me – sous chefing is when you are prepping the ‘strips of bacon’ or the ‘sandwiches’ or the layered-up clay – doing the parts that allow me to throw everything together in a more organized way. And a number of those shots were done by them as animators. They gave me a series of faces that were in the film so I worked on variations of them. I put a self-portrait in there. That was my one request (laughs).

The devil in the details...

How did you start breaking the sequence down? Were you given an idea by the directors or were you given free reign?

It was free reign. There was Blind Idiot God, which was a great soundtrack. And part of that was my manic-obsessive style, trying to attack. And the style is very Buzz Box. I’m slicing the clay but I am also strobing the lights. Often I am putting the light on a rotating rig, which is something I started doing in 1982 with Buzz Box. I would throw a light and put it in four different positions on four different frames continually to get the sense of something rotating around your sculpture while it is being cut away. This assaults your eye on every sixth frame. It does not attack the front surface – that has been lit well enough so you can get a cleaner image. This technique gives the sides energy and relief.

I would often place various background stratacut as ‘bacon strips’ on a piece of 4×4 plywood and I would shift that around randomly underneath so the background would have its own static energy. Everything was an in-camera matte. There were no special effects, there was no time to do any optical printing. The sculpture is put on glass and sometimes there are two or three layers of glass underneath that – it’s a crude version of an old Disney multi-plane camera.

At Cal Arts, for Buzz Box, I had to use the 16mm Oxberry which was based on a down-shooter camera. That allows support to the clay which is heavy and has a tendency to sag. Think of a Mayan temple rising upward with a shallow slope. Imagine the camera above the temple looking down on it. This allows you to keep the aspect ratio of what the limbs would be doing and I am trying to ensure the clay can support its own weight. Having one or two levels of glass to have things going on underneath creates a kinetic graphic overload. We did use 3D elements as well, like razor blades and knives because that makes it more exciting for lighting and you don’t know what textural intensity to expect.

Peter Gabriel "Big Time" music video frames

At one point you used celluloid for hair.

Exactly, celluloid for hair! Some of that was me and some of that Michael O’Donnell and some was Galen Beals. I was directing it stylistically but it was a group effort.

Did you have the Blind Idiot God/Henry Rollins track beforehand?

It came first and I edited the piece to that song. The song itself is so crazy that it wasn’t any trouble for the intensity and the images to go together. I was trying for larger edit arcs in the music, so I never micromanaged it down to the infinitesimal beats. I knew it would work well with my material.

In terms of mapping out the action, did you work from boards?

No, the great thing about the Freaked sculptures is that they were more like progression/explosion sculptures. I would begin at the bottom with a face I was aiming toward and then I would build free-form as I went higher. I already had the Worm-Man and the other characters from the film so I built from those [end frames].

Those kinds of stratacut are easier to do. I did a Sesame Street piece that had rotating numbers going on. Doing pieces that rotate in space and change their two-dimensional position from one side of the camera to the other are much more difficult to do and have to be thought out very clearly. But I didn’t storyboard much of anything. Sometimes I’ll draw a paint-by-numbers look of something. As I’m sous-chefing the materials I’m going to work with, essentially I make my palette like a painter does his colors – I need to fill a table of twisted log “colors” that are gradients: one part brown, two parts red, three parts white, and so forth. I stagger the gradients so that they all live in a different textual twist or a different kind of Seurat or Van Gogh pixelation – they all have to live at a particle level but they can also go from pure white to pure black.

After I’ve sous-chefed, I paint by numbers, creating the shadow for the cheek and the highlights for the brows. So I would sketch if I had a character I was trying to work toward. I would spend 15 minutes working on a thumbnail to make sure the gradients came out right. There is an Impressionist-inspired result.

The process is like juggling fireworks. You want to have everything as loud as possible in all different ways while maintaining a coherent strategy. I mean, clay comes in about twenty colors. It is possible to mix colors using a double boiler, which is a pot of water with another pot inside. You put the clay in and mix a pure color from that. It’s a lot of time and effort, which is one of the reasons I’ve developed a kind of Oaxacan-influenced primary color clash.

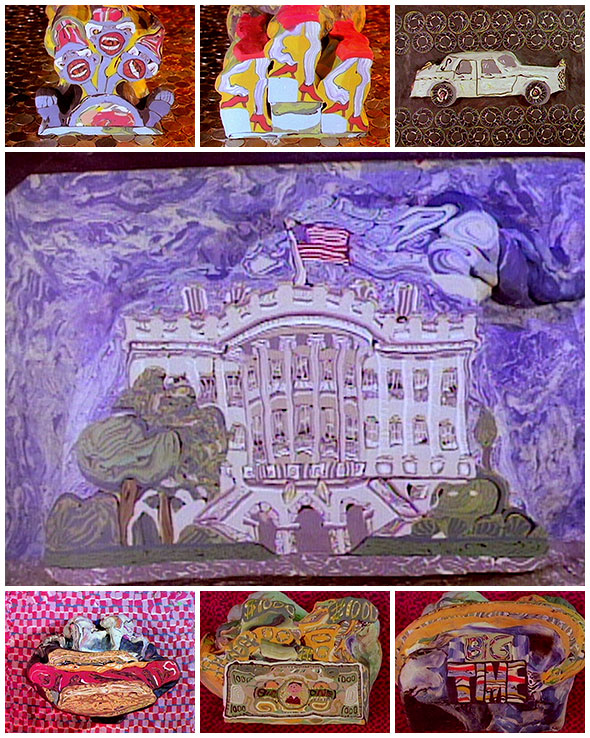

MTV cake

Right. In Freaked, there is a lot of smearing going on.

Yeah. Imagine the lens is about three feet above the animated action. I have the sheet of glass that is going to smash the image already in front of the lens for the entire process. It has to be there in a one-quarter or one-half f/stop optical density to the glass. Only at the moment where I’ve animated all the way down do I place a light bulb under the last frame of stratacut. I let it heat up and watch it carefully and when it is ready, I lower the glass and smash it really slowly. I am animating, it isn’t really live-action… it’s a kind of tai chi live-action where you take the shot and you let it melt a little more, and you smash it just a little bit harder, and it’s slowly oozing out and you are slowly twisting the glass and you are trying to raise the heat underneath. I’m glad you noticed that – it’s fun to smear!

Here is one way to think of the reverse engineering aspect of the work; if you were to take classic animation where you take key frames and, say, a Disney animator would take four frames to define key action, the in-betweener will come in for the in-betweens, but the key animator will only draw the significant action over time. So the key animator is gapping four or five frames out of the whole thing. It’s a four dimensional space seen in three dimensions. Time is simultaneous unto itself. The beginning, middle, and end all coexist at once and what we are seeing is human beings normally cannot: ourselves in extruded time. Time is this slice that we tick by but truthfully we are extruded pieces of spaghetti – much like stratacut – where we blob and shift and move and run. All our timepieces are connected but we can’t see them and don’t know it. In a sense, I’m putting those pieces together and giving you a sculpture of that time.

In the video you said you wanted to start animating with a pasta extruder and you gave an example for the stretch and smear effect. How did that develop for you and do you have any new techniques to share?

Wow, that’s a great point. You know, life is full of many dreams and in some ways dreaming them are more fun than doing them (laughs). Sometimes I will put a score along the extruded edge and have registration marks and you don’t see them. They’re tiny little dots and I can line things up after the fact because there are tiny pieces of clay that run the whole length. They’re not visually significant, you can’t tell they’re there and I can use them as registration marks to kinda line them up but it doesn’t always work because there is internal distortions inside of each slice depending on how the knife cuts it and the kind of surface tension of the knife as it goes through it that doesn’t allow it to be repeatable internally.

So I would use that and the pasta extruder to try to lay them out and re-align. I think with modern software, like After Effects and other digital tools, it gives you a cheap way to correct things. In 1992, when I did that video, it would have been very expensive to sit and reposition every single frame properly.

Pasta extruder method

The reason that I feel Blind Idiot God and Freaked looked good is because it was happening under the camera as a performance piece and there is a dimensionality aspect to some degree that’s actually part of what makes it interesting.

The front surface is only half of what’s interesting about it – it’s the contours in the sides and all the other stuff that’s actually sculptural that gives you the feeling of the entire event as it’s happening. The downside of doing a series of extruded pieces and then doing them after the fact is that if you do it really well people will say it’s a video effect. They’ll say the computer did that (laughs).

How controlled is it? Do accidents happen when you’re animating?

Nothing ever comes out where I think that shouldn’t have come out, but I do think it’s like jazz improvisation. You’re working with a series of core structures and you know you’re going to go through a series of emotional parts in the piece but you don’t know every note. I intentionally leave crudeness in the mix. I could control it more, but I choose not to because it is less interesting to look at. It becomes too controlled and too tame. The muscular, electrical effect of the natural, random stuff happening is a little bit large, a little bit crude, but it’s more interesting. It’s a wrestling match of trying to bottle lightning.

There’s a real fury to a lot of what you’re doing. Where does that come from?

People meet me and they think I should be more ragged and crazy than I look. I’m pretty low-key and normal on first handshake. But I had a lot of anger about life on the cosmic level, on the practical level, on the human level. There are a lot of philosophical things that eat me. I grew up during Richard Nixon and the Vietnam war and then just as things started to look like they weren’t as bad as I thought they were, we got Ronald Reagan and the machinery of deceit that his minions perfected. That’s just a small issue though, the real problem is that I’m alive and I’m going to die in a short time like everyone before me. I knew that from the age of four. You could see that everybody was an adult, struggling with details that don’t really matter, and I’m an adult now and it’s really tragic. I grew up to be that. So what you’re seeing is a lot of inner anger from not wanting to sell out and not wanting to become what I knew was ahead of me. And from the frustration of trying to shout at the top of my lungs in an artistic way to say, “There’s something on the other side here!” It’s all I can do to sort of explain that through time/space extrusion experiments, if you will. It dooms us to be a piece of spaghetti at the beginning of our lives and a piece of boiled pasta at the end.

Would you care to list any influences in animation and otherwise?

That’s tough. You know, after the fact, people told me about Oskar Fischinger but I was never really into him. I did like his puppettoons, but he did some wax cut stuff that I never really knew about until long after my work began to be seen. I really had no clues from any predecessor, so it’s hard to give Oskar credit ’cause it had absolutely nothing to do with what I was doing. His stuff is pattern-based and primitive.

Anyway, some people who inspired me! Einstein, Hegel, Herman Hess, Krishnamurti, Carlos Castaneda even though I think he’s full of shit but I read the books when I was young and they were fun (laughs). Artistically: Kandinsky, Munch, and first round of expressionist anger and the neo-expressionist painting in the ’80s and graphics, like RAW magazine. Chihuly is very pleasant and I think Gehry is very good. Van Gogh and the impressionists obviously made a big early impact when I was young. The Beatles, Menomena, Viva Voce, Peter Gabriel.

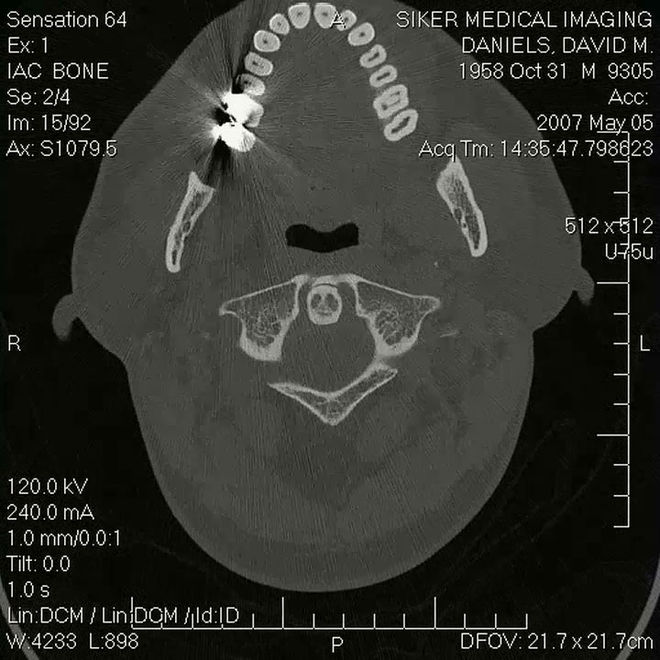

The mind of David Daniels by means of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Earlier you mentioned that you moved away from stratacut – what are you working on now? What gets you up in the morning?

I have a family and I run a business. Family brings serious adult responsibility and so I sort of took the easy way out. I would love to do actual sculptures that use pottery clay or a form of plastic and create things that would sit on your coffee table or could be very large that are the motion sculptures themselves. I would never cut them up but would put some kind of magnetic filament into them and MRI the things and sell them as gallery pieces. You’re looking at time from the outside. That’s my gift – I see time from the outside and I see motion sculpture and see how the pieces all flow together and we’re a part of all that. So when you see these things as sculpted pieces from the side, that’s when they’re the most beautiful. Showing something that nobody sees is a revelation and an artistic triumph. My medium is a transitory puddle of goo (laughs), so you just can’t sell it.

I also consider CG. It is the ultimate chameleon. It can be anything – including what I do – but there are so many things to communicate and I cannot even begin that process. I would have to make or work with programmers to make my own tools since these are mediums and techniques I don’t understand enough to actually do.

Also, agencies and creatives have become scared, to some degree, of the possibilities. When I was doing this in what I would call the heyday of the ’80s and ’90s, there was actually more openness to unusual things and to the possibility of a random outcome. They’re very scared of random outcomes now – they want control because everybody’s afraid – so I’m not getting as many pieces of commissioned work. These are all reasons why I’ve been away from stratacut but it is my natural talent and I should go back to it. Many people can run a company and lots of people can make good or even great commercials, so a great pool of talent already does the things I do all day long. Going back to stratacut would require economic and personal sacrifice, but I may be lucky in the next year or two and have enough of a cushion to go back to being a less angry, less crazy person and more of an artist who’s trying to find something in the work.

A Stratacut Demo by David Daniels, Part 1 of 5 — Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5