In the opening of Full Throttle, LucasArts’ groundbreaking 1995 point-and-click adventure game, the recollections of a road warrior are drowned out by the roar of motorcycle engines and electric guitars. This rollicking, rock 'n’ roll introduction to the high speed world of bikers and backstabbing is as impactful – and fun – as when it first hit PCs back in the mid ‘90s. The combination of motion, attitude, and music in Full Throttle’s opening moments was unlike anything most players had experienced in a video game before or since.

Full Throttle puts players in the role of Ben, a strong, silent type who won’t let anyone or anything get between him, his gang, and the road. But in true film noir tradition, something inevitably comes between him and the rest of the Polecats. Left for dead and with his gang shanghaied by an evil businessman, Ben sets off to punch things right.

Full Throttle (1995) promotional trailer

Developed and released at the height of LucasArts’ golden age of adventure games – an era that included titles like The Secret of Monkey Island and Day of the Tentacle – the stated goal of Full Throttle was to create a darker, more cinematic game, while still retaining that distinct sense of humour the company was known for. The project, led by writer/designer Tim Schafer ("I did it all on my own with about 30 other people"), was one of the most expensive and ambitious games produced by LucasArts until that point. Some of that expense can be attributed to the game’s opening sequence, which required the use of 3D modelling and streaming video tech that was still in its infancy.

Full Throttle’s opening title sequence is just a small part of what makes the game such a memorable experience. It doesn’t just leave an impression on players, it leaves skid marks! But the sequence, like game itself, represents a confluence of talent, technology, necessity, and vision that could only have happened when and where it did. It also helped show an entire medium, which at the time was largely obsessed with first person shooters, the true potential that games have to tell stories.

A discussion with Writer/Designer TIM SCHAFER and Lead Animator LARRY AHERN.

We don’t get a chance to speak with that many game developers about title sequences. So I'm most curious what you, as game designers, feel the role of an intro or title sequence is in a video game?

Tim: Well, of course it’s primarily to serve the ego of the developer. [laughs]

Members of the Full Throttle team in October 2016. From left: Lead Sound Designer Clint Bajakian, Composer Peter McConnell, Lead Programmer Stephen R. Shaw, Production Manager Casey Ackley, Lead Animator Larry Ahern, and Project Leader Tim Schafer.

No! I mean, there’s the tiniest bit of truth to that, but there’s all these practical reasons that we can get into. Video games always seemed aspirational, especially around that time in the late ‘90s when it started to become more and more possible to become cinematic. Mario was not an incredibly cinematic game, but in the ‘90s we were always thinking, “We could do stories just like movies do!” Therefore, opening credits.

Looking at your Fallout feature, I think Brian [Fargo] and I – not that we wanted to be making movies – but there’s a lot to the immersion you get from a really great film, when a really great title sequence starts and you’re just pulled into the mood really quickly. The music, the typography, and everything pulls you in and the escapism begins.

Larry: Yeah, it’s all about setting the tone, setting up expectations for what the flavour of the game is going to be. This is your first look at the world and the characters. It doesn’t necessarily have to introduce everybody, but you want to get a sense – visually and stylistically – of what’s going on and what’s at stake. It may not entirely set that up in all cases, but it’s at least going to hint at it. In the case of Full Throttle we actually set up quite a bit, but I don’t think that’s always necessary. It’s really more about the flavour.

Tim: I’ve always loved that the credits were a part of it too. You’re transitioning into this fantasy world, but human beings made it. Look at all these people who worked on this thing! You’re about to enjoy this thing that all of these people got together and made for you. All this entertainment is because of these people. More than anything I think the opening credits in a game are a list of people saying “Enjoy!”

In the early 1990s the games coming out of LucasArts were getting far more dynamic and ambitious. Was it simply the technology catching up to your desire to do these new things or did something else change?

Tim: For each game it was a decision based on the genre that we were doing. Day of the Tentacle had a silly, cartoony Chuck Jones vibe to it, so we wanted to do a silly Chuck Jones type intro. What would a Chuck Jones animated feature have as an intro?

Day of the Tentacle (1993) main titles

Larry: A lot of games around that time had some animation and maybe were a bit cartoony, but we wanted to push that a little bit further with Day of the Tentacle. It felt like the art in a lot of video games back then was all of a similar flavour, partly because of technical limitations and maybe partly because a lot of people were in the same mindset. So we were really interested in trying to break out from that and do something stylistically different. We’d just come off of that before Full Throttle and I think maybe it was the pendulum swinging the other way. “Let’s do something darker!” We were still thinking comedic, but it was more caricatured and a bit of a black comedy.

So let’s talk about Full Throttle. What were some of your inspirations for the game and specifically its opening?

Tim: With Full Throttle it was obviously inspired by The Road Warrior – that was my favourite movie and it’s still one of my favourite movies. It was really the inspirations for that game that gave us the inspirations for the titles.

—Tim SchaferThe Road Warrior was a big influence on the game.

Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior (1981) main titles

Tim: The Road Warrior was a big influence on the game, although it’s not a post-apocalyptic game it’s still that loner on the road. Everyone thinks it’s a post-apocalyptic game, but it’s just an alternate future. No bomb has gone off. They’re still producing motorcycles so there’s obviously still some sort of industry. It’s actually a more optimistic view of the American vehicle manufacturing scene than turned out to be true. [laughs] I’m going to get letters from angry Harley fans.

So yeah, that was obviously a big influence if you look at the opening credits. That low angle that George Miller so relied on for all his Road Warrior movies. The camera on the ground, racing, it made everything feel so fast and exciting. You can see that in the opening credits for Full Throttle.

But one thing that I forgot about until recently is Marlon Brando’s The Wild One. If you watch the opening credits for The Wild One it’s almost embarrassing. I was like, “Oh yeah! I lifted the whole title sequence from this!” [laughs] Not really, but there’s a long shot of a road and there’s a dude talking about a girl.

The Wild One (1953) main titles

Tim: It’s a little bit film noir, like that whole era of film. There always this guy talking about how it all started with this one crazy dame. A film noir story is often about a normal guy who just meets the wrong person – usually a femme fatale character – who spins him off his normal trajectory into a dark shadowy world of blah blah blah.

There is definitely a strain of that in Full Throttle…

Tim: Yeah! Although the girl turns out to be your salvation in this game and it’s Ripburger who’s the person you shouldn’t have met. But yeah, it’s not giving you the whole setup of the story, it’s giving you the mood, almost like the aftermath. “Everything was great until this one day…” and that gets you all set up. Hopefully you feel like you’re going to experience something great.

Do you remember any of the initial conversations you had with the team about creating the opening sequence?

Tim Schafer, circa 1995

Tim: Uh, no. [laughs] I honestly feel like this thing just formed in my mind and it was just like, “This is how it has to be.” There has to be this opening sequence where you’re racing down the road and Ben is talking about it. Peter Chan storyboarded it all out.

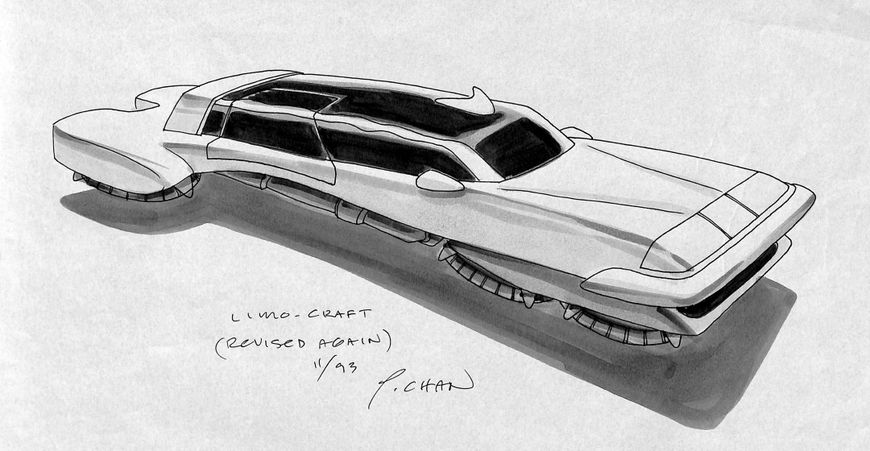

Larry: Tim had roughed out a concept for how he wanted to set it up. He worked with Peter on developing that panoramic shot that established that big, desolate world. I remember us talking about wanting to have one of those crazy biker intros where you get the camera down next to the road and it’s like a stampede flying by. We want to introduce this guys on the road, at high speed.

We tried to figure out a scenario introducing Corley as the head of the company and then our villain character. We thought we could have them arguing about something on the road and then have the bikes go flying by and interrupt it in a loud cloud of dust. At first we were thinking “Okay, the bikes just go flying by and that’s cool, but is that enough to interrupt it?” So then we got to Ben popping a wheelie and going right over the top. That was the vibe of what we were trying to do with that game. He’s not just going to drive by and bump the limo, he’s going to drive right over top of it!

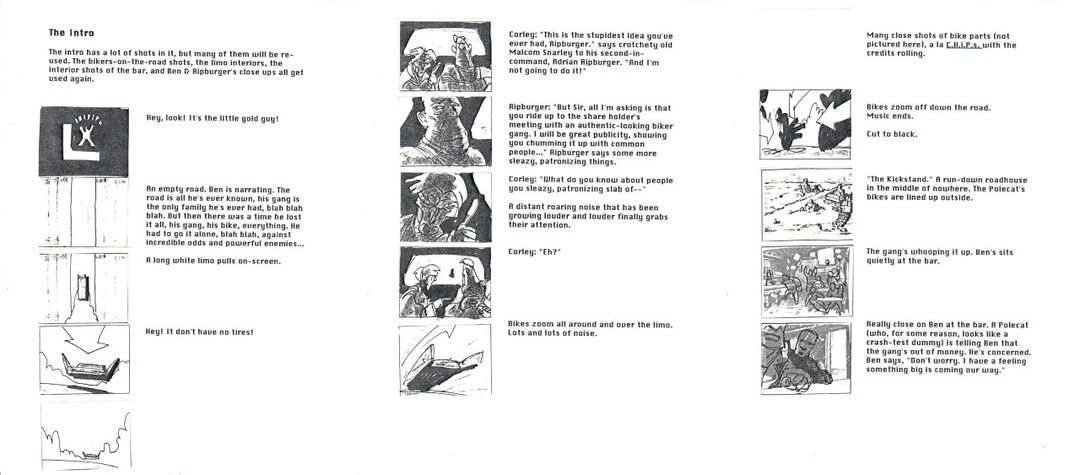

Tim: Let me see if there’s anything in my Full Throttle binder here. Yeah, I can see that I’m already defensive about the expense of it: “The intro has a lot of shots in it, but many of them will be reused.” [laughs] “The bikers on the road shots, the limo interiors, the interiors shots of the bar, and Ben and Ripburger’s close-ups all get used again.” These aren’t just wasted and thrown away, they can all come back! Things were so tight.

Image set: Full Throttle (1995) design document excerpts outlining the game's intro and title sequence.

So once you had those storyboards, what happened next? What was the process for creating a shot from there?

Tim: As far as I remember, we would do those storyboards, then an artist would create a 2D background, then the animators would take them into Deluxe Paint to enhance them and paint the animations for each of those.

Larry: DPaint was the industry standard back in the ‘90s. It was Deluxe Paint the pixel painting program and then Deluxe Paint Animation. I think the entire production of Full Throttle was on that. We’d figure out the basic concept of what we wanted for the scene and put some thumbnails together. Then we went to the animatic stage and did a grayscale version of those shots to have some placeholder and figure out the kind of impact it would have. No details, no colour, or anything, and then just text for the dialogue to see how the whole scene would work.

—Larry AhernWe were digging out books on storyboarding for films and setting up shots.

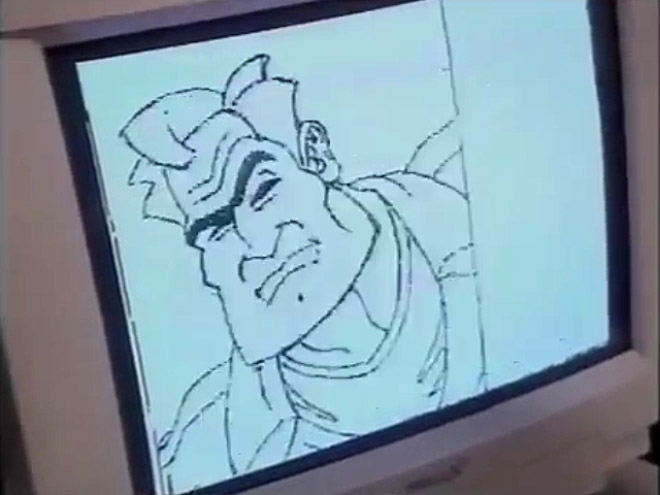

A 1994 interview with Full Throttle Lead Animator Larry Ahern

Larry: It was funny because most of us were straight out of school and didn’t even necessarily have a background in film or animation. I actually learned to animate on the job! [laughs] I’d always been a cartoonist and an illustrator so I did a lot of drawing like that, but other than a few short pieces that I’d done in a college art class I really didn’t have any experience with it. The great thing about video games back then was that the technology was so limited that even the most experienced people weren't doing that much stuff.

When I first started in 1990, there just wasn’t much you could do with animation. It was literally like the A team and the B team. If you were the A team, they’d throw you at the background paintings. “Hey, we’ve got 256 colours! This guy’s good. Put him to work!” or “You new guys? Uh… I don’t know about you. We’ll have you animate,” because the characters were so small. But a year or two later you had more colours, more pixels, we could do more. It just kept growing and by [Full Throttle] I had been doing it all day long for years and had figured it out. It was sort of the same thing that was happening in terms of us planning the sequences. We were digging out books on storyboarding for films and setting up shots, just trying to figure out how to stage sequences.

What can you tell me about the 3D elements in the sequence? The limo and the bikes. That was still early days for that tech when you were developing the game, right?

Tim: A lot of this was done the old fashioned way. When Malcolm and Ripburger are talking we’re using our regular, in-game engine for that. We’re drawing that in the same way we draw a character walking around the screen. The 3D was all new though. Our 3D art team would render those out and I believe we took those renders frame by frame and a 2D artist would paint over them. We didn’t have shaders or anything that looked nice, so that’s how that came about.

But the part where the bikers are going down the road, that is a streaming piece of video, a pre-rendered FMV [full motion video]. So when the bikes come down the road and jump on top of the limo and smash the hood ornament – which is me naked, not my idea – that’s all pre-rendered. Then when you go to the cuts for Ben’s arm, his face, his cheek, where the title cards come up, that’s all in-engine. So it’s a mix of in-engine and pre-rendered video.

Was that the INSANE engine you were using for the pre-rendered video?

Script Creation Utility for Maniac Mansion (SCUMM) is a video game engine developed at Lucasfilm Games (later LucasArts), to ease development on their first graphic adventure game Maniac Mansion (1987). It was subsequently used as the engine for later LucasArts adventure games.

Larry: Yeah, so the INSANE engine was used in Rebel Assault. Vince Lee wrote it. If I understand it correctly, it just let us play these complex 3D streaming video scenes. You could just drop it into the SCUMM engine and use it that way.

Tim: Rebel Assault was one of the first CD-ROMs Lucas ever made. You were going down a pre-rendered trench and you’re moving your TIE Fighter or your X-Wing in front of it. We just shortened the trench and we made it like a road. We change the road a little bit, but we used Vince’s INSANE engine. It was the same technology as Rebel Assault, but instead of space ships we used bikes.

Star Wars: Rebel Assault (1993) gameplay

Larry: That was the thing that allowed us to do that big opening shot like that with the 3D video and the camera moving through it. It was a huge deal back then! A lot of the shots where we’d tried to go full screen in Day of the Tentacle were still basically limited by the number of pixels that could move on the screen. I forget what it was, but it was like you could only have like 30% of the pixels on the screen change at any one time, something weird like that. So it was a big deal getting the INSANE engine in this opening because it let us stream this complex, full colour video. It was just crazy! It just opened up our ability to do these cinematic shots we’d never done before. “If only we had enough animators to do something with it that would be amazing!” [laugh] So we faked it. It was a lot about faking it.

Tim: We were always talking about and going up against the budget and time. We were doing this really cinematic game, but you could not move that many pixels on the screen in the older games or else the computers would just bog down. We wanted to do all these big full screen things, so it was like, “Well, what can we do without actually moving that many pixels on screen?” So if you look at the title cards around Ben’s bike they’re almost still images with this rippling edge or flap. The leather is flapping or the shadow is wiggling. That pan down at the start to show the road is just a static piece of art. We were trying to be really minimalist.

The CHiPs (1977) title sequence inspired the close-up shots in the Full Throttle opening credits.

It’s a very convincing effect, no matter howmuch "faking" was involved.

Larry: For those close-up shots, Peter ended up going in there and painting over the pipes and that kind of thing. It’s really got sort of a three or four colour value on the chrome to make it really graphic. So it wasn’t getting the gradient curve that you would get from the original full colour version. Rich Green was helping us figure out how to process the images and crunch the palette down to real simple, limited colours so you still retain the shape of the 3D model but you don’t get the level of detail there. That was the look we wanted. We were really trying to shoot for making it look more like a graphic novel. Some of the stuff that we were excited about at the time were Mike Mignola’s Hellboy comics. He used such heavy ink and the shadows would go to pure black. So we did a bunch of that in there. We just loved that vibe that made it feel like a comic book come to life.

I’d never made that connection, but I can really see the Mignola influence now that you mention it. So back to the 3D, that was technically ambitious for the time, wasn’t it?

Tim: It was very technically ambitious to use 3D at all for us as a studio. We hadn’t really done much at that point. They were working on Dark Forces next door, which was our first 3D game at the company.

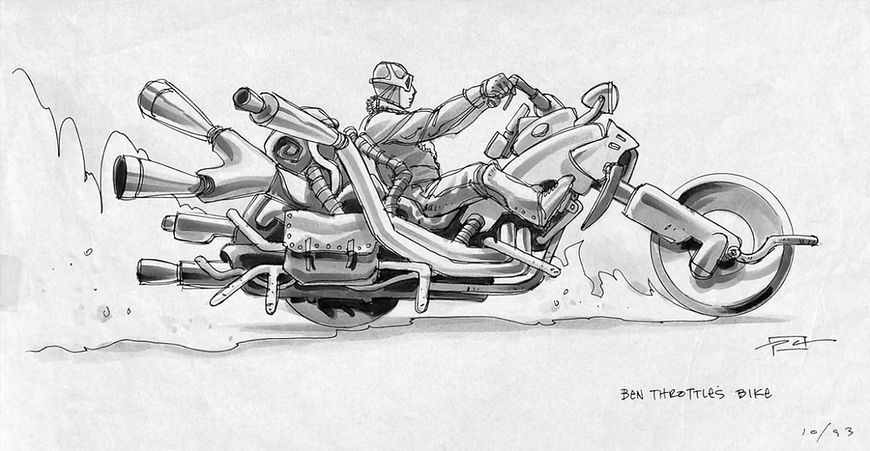

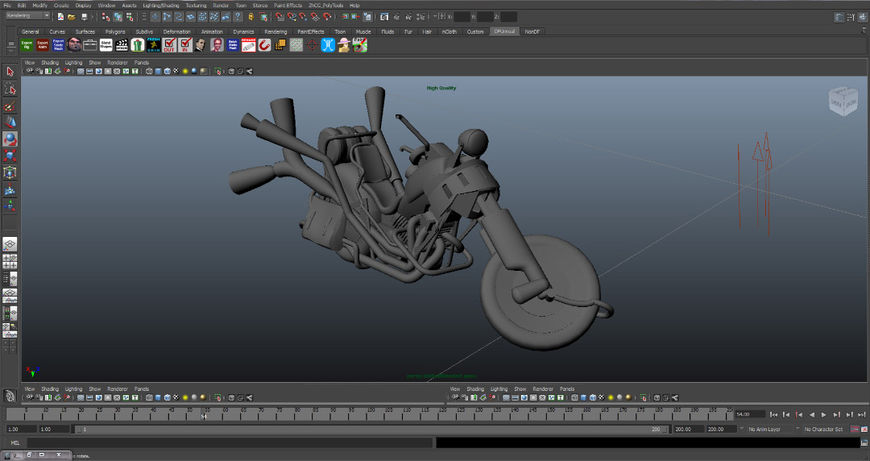

Larry: Yeah, definitely! Some of the flight simulators before that had used 3D, but I don’t think we had done it on the adventure games side. It was a big deal trying to figure that out. We just knew there was no way we could draw all those motorcycles – there was just no way we could do it, especially with the cameras moving. But we were concerned that trying to merge the 3D bikes and vehicles with the 2D characters might not look like they were in the same world. A lot of it was just figuring out how are you going to put the character on the bike. When it was other vehicles it wasn’t an issue because they were just in the cab or the car or what have you, but the bikes got a little trickier. We had 3D models for all the characters on the bikes, but they were not necessarily matched to the 2D. I think what we did was we just had a generic model,

Tim: The bikers are all Ben. It’s all the same model, painted over a bit, but we wanted to save money there.

Ben's bike and limo concept art by Peter Chan

Did the case ever have to be made to the brass to do this title sequence? I imagine the file size of the games was a big concern in those days and a sequence like this must have taken up a lot of memory – and cost a lot of money to produce.

Larry: I know with the earlier games it was a big issue because we were shipping on floppy disks. [laughs] If you add more, you’re going to add another disk and that’s going to take away all these profits! But by this point we were CD-ROM so it just felt like there was a crazy amount of room available. I think at the time we were more like “We can do anything!” From my perspective it was more, “Yeah, but do I have enough people or time?”

Tim: The title sequence was kind of hidden inside the budget of the project overall. But there was always kind of a sense of “Is that person being extravagant and being loose with the budget? Has the project leader gone full Apocalypse Now and vanished into the jungle with all of our money?” [laughs] So you were always trying to explain, “Nope, nope, nope! This is really a smart move. This opening is really economical.” I feel like it is pretty… okay, well, actually there was a lot of 3D and we’d never done 3D before. It was the first time modelling 3D bikes and stuff, so it was a really big expensive cutscene. But the talking back and forth between Ripburger and Malcolm Corley was not super expensive.

As Tim mentioned, he has a very brief, very nude cameo in the title sequence. What’s the story behind that?

Larry: I gave one of our animators, Charlie Ramos, that shot. I want to say he was fairly new on the job at that point. I don’t even recall if we talked about it, but we knew there was a hood ornament on there because the model had one. I’m guessing it came from Peter’s concept sketch and then got built into the 3D model. For that one shot Charlie’s got that thing right up in our face. That’s gonna be the impactful shot! We’re not going to look at Ben’s face or anything, we’re just going to show it jump over the back of the limo and then on the front have it crash down and destroy the hood ornament. We probably just said “OK, well, you’re going to have to figure out what that looks like.”

Tim Schafer's in-game cameo as seen in Full Throttle Remastered (2017)

Larry: Then I remember coming back and looking over his shoulder and he’d done this caricature of Tim. I was laughing my head off. “Looks good to me! Hopefully Tim won’t notice it.” [laughs]

Tim: I was not expecting to have a nude scene in the game so early, but that was a gift from the animation department. Whatever is needed for the plot!

[laughs] Did the sequence change much during production?

Larry: Early on we had been thinking of Ben as this cigar-smoking, tough talkin’, ass kickin’ character, but then we started to consider “Can we have this guy walking around smoking a cigar?” Games have ratings. Obviously they rate you for things like violence, sexual content, and other things like that, but one of those things that actually ends up on the label is “Use of Tobacco Products”. We really wanted to do that, but we weren’t sure if we could. I’m not sure if we ran it by the higher ups and got shot down or if we just thought it was too risky to have him smoking all the time. I remember when we put it together we were like, “Yeah, but he’s got to be smoking a cigar in the opening!” We loved the idea of him smoking a cigar and then he just flicks it at the camera. That’s the attitude we wanted! It’s busting the guy’s hood ornament and then flicking the cigar at the camera when he realizes we’re looking at him. “Screw you!”

—Larry AhernCan we have this guy walking around smoking a cigar?

So we wanted to do that and I’m pretty sure we’d mapped out that whole scene to be prepared to have to take that out and exchange those shots. Let’s try to sell it with that and hopefully management will go for it, but be prepared to paint out the cigar and change the scene if we can’t do it. But we ran it up the flagpole, flinched waiting for the reaction, but they loved it. I’m sure it got that rating warning. Tobacco products. Look out! [laughs]

So let’s talk about the music. At what point did The Gone Jackals get involved? Did you have any other songs in mind before that?

Tim: Peter McConnell was the composer who worked on every game we’d ever done up until that point. He wanted to compose some music for it, but we also thought we should use a real band, like a real biker band, you know? We were looking around and the company was thinking about licensing music, but it was pretty early for licensing music for games in those days. You didn’t have Rock Band, you didn’t have Brütal Legend. So we were like, “What about Soundgarden?” They had a song called “Kickstand” and we have this location, a bar called The Kickstand”. The song really fit, so we thought we should try to get it. So we went down to LA and had a meeting with A&M Records, but they quickly realized we weren’t going to pay them any money and that we just wanted them to give it to us for free. So that didn’t end up happening.

The Gone Jackals circa 1995. From left: Brian Sutter (drums), Judd Austin (guitar and vox), Keith Karloff (vox and guitar), and Warren America (bass).

But then one day this guy Keith Karloff, who was the lead singer for The Gone Jackals, rode up on a Harley and delivered his cassette tape demo. We listened to it and were like “This is perfect!” We can get all our music from one band. It’s a local band so it’ll be a little more legit.

He just got wind that you guys were making a biker game and rode up?

Tim: Peter McConnell must have put out a call on local message boards or something…

That’s quite an image: a guy riding up to the studio on a Harley with a cassette tape!

Tim: That was the clincher.

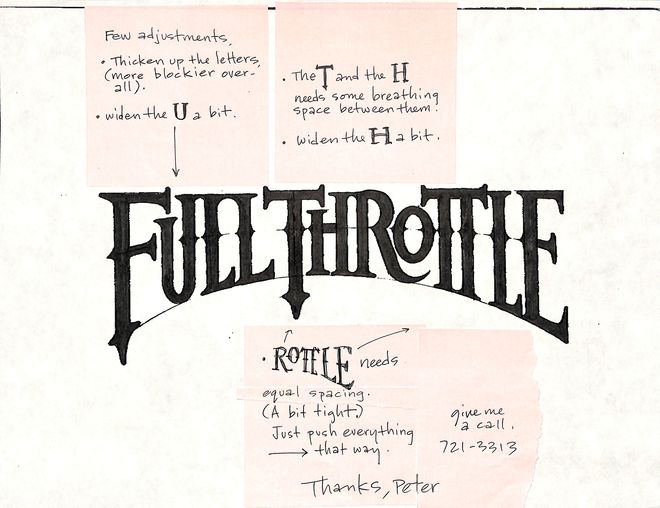

Who designed the game’s logo?

Tim: That must be Peter Chan, he was our Lead Artist on that project. I don’t know what reference he was using. It’s not like the Harley Davidson logo or any metal band I know... It always felt to me like it had a little bit of a Western vibe at least. I wonder if it was the Hell’s Angels? I read Hunter S. Thompson’s Hell’s Angels book when I was getting ready for this game. It looks a little bit more like the Hell’s Angels, especially the swollen Ls, the pregnant Ls if you will. Let’s go with that story… Very inspired by the Hell’s Angels.

An early iteration of the Full Throttle logo designed by Peter Chan

Tim: There’s a Hell’s Angels nest in what we call Dog Patch now, it’s a part of San Francisco. I remember during Full Throttle’s development I was at my girlfriend’s house in Potrero Hill. There’s a pedestrian bridge over the freeway and this guy came roaring around the corner on this Harley with the straight pipes, long chopper forks. super loud. He had this sleeveless denim vest. I remember being like, “What is this guy doing?” He came down this cul-de-sac, pops up, goes over the curb and between these cement posts, and does a wheelie over the pedestrian bridge. But he didn’t even pause and think about it! [Tim makes motorcycle sound effects] I was like, “Man, bikers just do not live in our world. They live in this other reality where they can do that!”

[laughs] I can see how that encounter might have inspired you a bit with this game. So was there anything that took you by surprise when working on this project?

Tim: Well, this game was our most ambitious title to date. We did not realize how much we had signed ourselves up for. We had this idea that it will be really cinematic but we would cut so much that we wouldn’t have to animate too much. We’ll cut to a face, then we’ll cut to a fist, and then we’ll cut to a bike. It’ll just be these short cuts and it’ll be very economical. But the game went way over budget. It was our first over a million dollar game. I remember the producer saying, “Do you know how much money this game is going to be?” I asked, “Is it over a million?” And she was like, “It’s a million dollars!” And I was like, “Yeah!” We’d never made a game that expensive before.

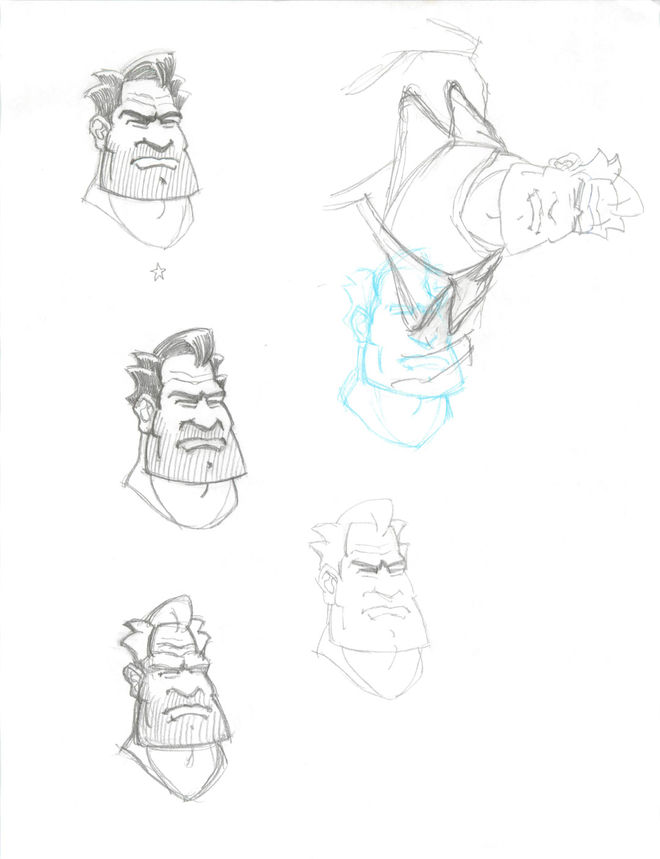

Image set: Early character concept sketches

But we ended up cutting a lot from the game just to get it done. It ended up a little shorter than our previous games and people were a little mad about that. I feel like nowadays that play length of like eight to ten hours is pretty long for a game. It’s pretty typical for a game now. People almost don’t want a game that long. In the old days adventure games were 40 hours and most people would say “40 hours? Who’s got time for a 40 hour game?” And that was our biggest hit! That was our biggest adventure game hit. Our director of development was like “My friend loved this game. She said this is the first adventure game she’s ever finished.” Maybe that’s the secret? Let people finish these games so they can tell their friends about it.

Larry, did anything take you by surprise working on this?

Larry: We were just excited to do something cinematic like that. Part of the vibe at LucasArts back then was that we were all too stupid to know that we couldn’t do what we were doing, you know what I mean? “Of course! We will make this epic thing!” [laughs] That was kind of the flavour of things back then. We’ll do anything and everything. It did start to bite us in the ass on this project. We all talked about how Day of the Tentacle was the last great project and then things got really hard because we bit off more than we could chew on Full Throttle, and it’s been that way ever since.

Is there a particular moment or element of the sequence that you're most happy with?

Tim: When I write these I work a lot to hone them down. With the first draft I tend to overwrite it. No one wants to watch a long title sequence, you know? They’re expansive, but you also want to start playing, so you want to make ‘em short. But I try to make every single line of dialogue say eight different things. I try to set up all the characters and their relationships and the tension and everything just right. Watching it years later I feel like, “Oh that’s very economical! I’m very pleased with myself. Good editing!”

I love both the voices. I love Hamilton Camp’s voice, the voice of Malcolm Corley, and also Mark Hamill, who did the voice of Adrian Ripburger. It was just really fun to write a dramatic opening like that, where someone is talking wistfully about the past or talking about the smell of asphalt and a girl. That’s just fun writing to do.

Larry: The pan shot just felt like it was epic. We hadn’t seen something like that before. I just love the fact that we got camera motion. That pan shot was a 2D shot, but Peter designed it so it really warps and feels more dimensional than it really is. I just love the fact that we got a moving camera into our scene. We’re zooming in on the limo as he pops a wheelie and you see him go over the back. You see the wheel lift off the ground and the hover limo bounces down and we zoom into that. I love the camera flying down the road weaving in and out of the bikes. For me that felt really exciting and new. Obviously for video games it was a new thing as well.

So let’s talk a little bit about Full Throttle Remastered. What has it been like revisiting games like Day of the Tentacle and Full Throttle that you worked on so many years ago? Obviously there’s some baggage associated with a Lucas product being revisited by its creator decades later...

Tim: Yeah! That’s the lesson for this kind of thing. I never really want to change the game, I want to make it look like it looks in people’s memories. No one remembers it the way it looked. If you really look at the pixels from the old version you’re like, “Oh my god, I forgot how jaggy that game was!” In your head you’re kind of thinking of it as cartoony. It’s smoother in your head. So we try to match that. In some ways, the less people notice it the better.

Full Throttle Remastered (2017) main titles

Tim: But we painted many, many cels of full screen animation – more than any of our previous remasters – just painting and painting and painting to make them look great. We change little things though. There are definitely outstanding bugs, crashes and stuff, that we want to make sure aren’t in this new version. We always see it as like we’re doing a Criterion Blu-ray version of an old movie. We want to preserve it as it was and make it look as nice as possible. We do add to it in that the aspect ratio makes it full screen. We may have to paint some new information, but we had the original Lead Artist and Lead Animator around to ask question and get approvals. We sent the new versions of the characters over to them for approvals. It’s really just about making it work hopefully the way people remember it. There’s a couple of things that are glitchy in the old one that we want to fix so it’s better. There’s one puzzle in particular that we made a tiny bit easier, but I don’t want to say. [laughs]

Did the remastering process on this project present any challenges that you weren’t expecting?

Tim: No, but the biggest challenge in remastering is the digital archaeology involved. We got to go to the Ranch [Skywalker Ranch], go to the archives, and we got to dig through the old files. We got tubs of DAT tapes that we had to rip onto a hard drive. Uncompressed, unedited. We basically recut every line of dialogue. In the old days you would compress voice down a little bit, so now it’s going to be beautiful. You’d maybe have also used a MIDI sample for something that didn’t exactly sound like a violin, so we got to go in and replace those with something digital or a better sample, and just bringing the music up to its full glory. We also had a little reunion. We got the team back together to record a commentary track.

The original 3D bike model (top) was recovered from an archive and used in the remastered version (bottom).

Tim: It feels like taking care of something you made. Like taking care of, well, not a child… maybe a child. You made something and they stop working after a while. They just break. People can’t run them and people definitely can’t buy them. To their credit, the players are really resourceful about keeping old games alive, but there’s always this urge to really take care of it in a way that only the original creators could. We know where all that concept art is hidden. We know what that pixelated emblem on his chest was supposed to look like, you know? We can restore it in a way that no one else could. So we wanted to do it. It was fun get together with the old team. I’ve been making games for a long time now, and it’s great to be able to stand by your oldest work, to be able to just look at it and say, “Yeah! This thing still works!” Just kind of polish this off, make sure it’s not cracked, take this thing off here, and rebuild it. Still works! People talk a lot about games as service, but this is sort of like servicing our old games.

It’s really great that you and the team get to preserve it like this on your own terms.

Tim: Yeah! And then we went in and replaced all the guns with walkie talkies.

[laughs] Of course!

Tim: I probably shouldn’t make that joke. [laughs]

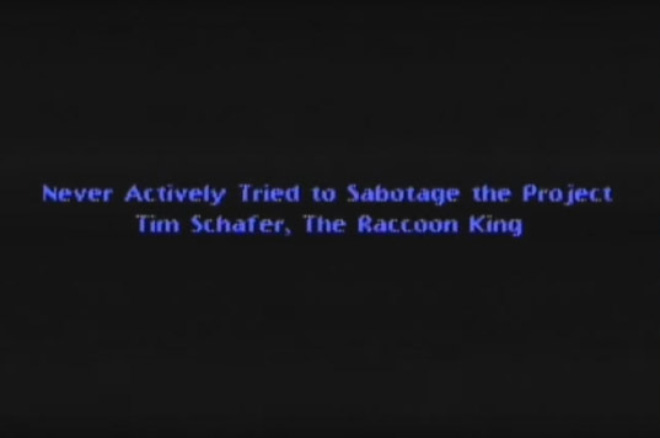

I have a credit related question about your time at LucasArts. Tim, you were credited on two Star Wars games not as “Designer” or “Project Leader” but as “Never Actively Tried to Sabotage the Project”. How did you end up with those credits?

Tim: Are you accusing me of trying to sabotage projects? Because I didn’t!

I wouldn’t dream of it!

Tim: We shared a lot of technology with the other projects and we also sat next to them. We were making this game, Full Throttle, right next to the Dark Forces team, or Grim Fandango right around the corner from podracer team, so we were very friendly and we’d go to lunch together. I forget how that came up, but the discussion was kind of like, “You’ve got to give me a credit in the game.” They were like, “What? What did you do at all for this project? You didn’t do anything!” And I was like “Well, I never actively tried to sabotage the project.” I could have, but I didn’t! So that’s something.

Tim Schafer's credit on Star Wars: Shadows of the Empire (1996)

Tim: It was more just a sign of the old days at Lucas when there was a collegiate vibe and kind of a back and forth between the projects. You know, Sam & Max easter eggs hidden in different games. Just a really fun creative campus environment.

What are some of your favourite title sequences, whether classic or contemporary?

Larry: I loved The Pink Panther, most of the James Bond titles. I know I liked the new Casino Royale too.

The Pink Panther (1973) main titles, produced by DePatie-Freleng

Larry: Monty Python's The Meaning of Life. Is the pirate short considered part of that? The Terry Gilliam animation stuff is cool either way.

Tim: I love film noir and I love classic films. I don’t want to call it campy, but I love Casablanca so much. The opening title just fucking goes for it! DUN DUN DUN! There’s a globe spinning in this mist. This is how it was! We’re not trying to act cool about this. This is a fucking world war! This is a dramatic story we’re about to tell you.

—Tim SchaferWe’re not trying to act cool about this. This is a fucking world war!

Casablanca (1942) main titles

Tim: I don’t remember the exact words, but I just love that opening narration: “And then people came to Casablanca to wait, and wait, and wait…” That’s one of my favourite intros and favourite movies of all time.

The Road Warrior is also great. Not so much the narration of the backstory of the war and the guzzolene. That montage of the credits is okay, but I just love the way it starts with the close-up of Mel Gibson and his air blower just halfway off the screen just super loud with this end of the world brass playing. The actual credits sequence is fine, but that moment is just wow.

What else? Does everyone just say Panic Room?

Fight Club and Se7en are popular picks… Anything by David Fincher.

Tim: Yeah yeah! I can’t separate Se7en from the beginning of that art style. It’s like, from now on we’re going to do jiggly, spastic letters that flicker and remain!

Modern movies are so sorry about the titles. “We’re sorry! We’re sorry about titles! There’s no titles! No, no the movie’s starting. Please don’t leave the theatre!” Old movies are like, “Here’s the book and I am going to tell you a story! Get ready for a story because this is going to be amazing.” Blue Velvet and Wild at Heart are both like, “Yeah, watch my credits. Here’s some flames and you’re going to watch them, and here’s some blue velvet.” I don’t know if I’d want my credits to be that long, but I admire that.

What else? I mean, everything by Saul Bass. Everyone loves Saul Bass, right? Vertigo. All the weird eyeball stuff. I love Dr. Strangelove. That’s the same artist who did the Talking Heads movie, right? Stop Making Sense. Thomas Crown Affair definitely. A-ha! Well, now I’m just scrolling through and enjoying your fine website.