The year was 1964, and a simmering unease was spreading across the United States. The Cuban Missile Crisis, the testing of nuclear weapons by the superpowers of the time, the assassination of John F. Kennedy, the Boston Strangler, the murder of Kitty Genovese – these were all fresh in the minds of Americans. It was in this climate that a new film genre emerged and began to take hold – a little too close to home.

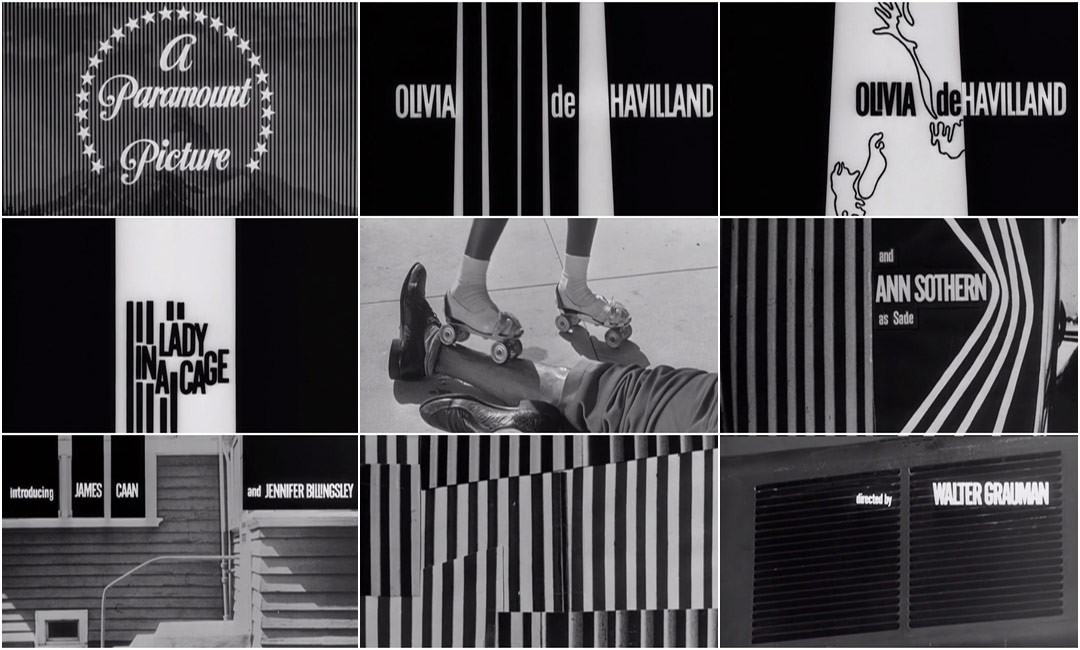

From the first frame of Lady in a Cage – the opening Paramount logo encased in vertical stripes – we’re made aware that this is a film envisioned as a whole, as an amalgam of parts fused to fit just so. In the film, Olivia de Havilland plays an injured middle-aged woman trapped between floors in her home elevator on a hot summer’s day. Quickly, her world comes crashing down around her, and forces beyond her control and her home invade. The film is a surprisingly savage thriller that walks a delicate line between comically dark social commentary and terrible cruelty. Director Walter Grauman, known primarily for his TV work and B-movies, here emphasizes cinematography (by golden age pictureman Lee Garmes) and an attention to detail. The end result is both aesthetically striking and unsettling.

The opening title sequence designed by Tri-Arts, a studio helmed by art director and animator Bob Guidi, pulls from a selection of first-rate influences. The combination of thick animated stripes and minimalistic photography descends directly from Saul Bass, with several live-action frames echoing Hitchcock and Preminger.

The smooth score by composer Paul Glass punctuates the graphic movements in a gestural jazz, almost a wild mimicry of urban traffic sounds.

Image Set: Stills from the opening titles of Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho (1960) (top) and Otto Preminger's The Man With the Golden Arm (1955) (bottom), both designed by Saul Bass

The sequence features a number of shots meant to disturb: a girl rolling her skate up and down a prostrate man’s leg, a dog lying dead in the street as drivers cruise past.

These scenes are as intriguing as they are disconcerting. They also mirror later events, creating a bookend with the closing moments of the film. At the end of the sequence, the camera moves clandestinely into the home of the titular lady through an air vent. The viewer is made complicit in the act, penetrating the sanctity of the home, highlighting the vulnerability of domesticity, the fallacy of the walls we erect. A sign of the times.

In the 1950s and 60s, a sense of social unease had begun to ripple through the United States, reflecting an increased fear of the other and a deterioration of the barrier between public and private spaces. The world seemed more volatile and violent than ever before, and film grabbed on to that mood and held tight. The influence of this and other home invasion movies like Dial M For Murder, Cape Fear, and Wait Until Dark still lingers, of course. It can be seen in modern thrillers like Panic Room and – particularly in its opening sequence – Outbreak.

The Lady in a Cage end title card featuring Olivia de Havilland

Titles designed by: Tri-Arts, Robert P. Guidi

Music composed and conducted by: Paul Glass

LIKE THIS FEATURE?