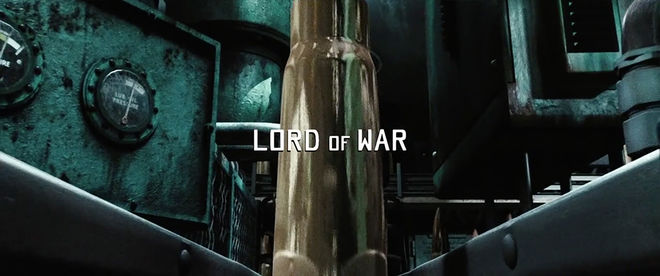

The opening title sequence of Andrew Niccol’s 2005 film Lord of War, starring Nicolas Cage as arms dealer Yuri Orlov, is a tale of birth and death. The life of a bullet. The death of a child.

The title sequence, conceptualized by Niccol and shepherded by Visual Effects Supervisor Yann Blondel with production studio l'E.S.T., is one that is technically and thematically exceptional. In placing the viewer in the position of an inanimate object on the move and pairing it with an iconic protest song, the film immediately sets itself apart, announcing its artifice while introducing its key ideas. The sequence establishes the narrative world of gunrunning, the story’s wry, tongue-in-cheek tone, as well as the film’s primary motif: the lone bullet.

The bullet in the title sequence is our entry point to the film but it’s also a symbolic representation of main character Yuri Orlov. Just as Forrest Gump is the feather, floating on the breeze and falling haphazardly into his fate, Yuri is the bullet, single-minded and on a deadly and inevitable course. Yuri also wears a bullet around his neck, a constant reminder and talisman of power. The lone bullet is a constant presence, providing the potential for change early on as well as the power behind the climactic scene between Yuri and his brother Vitali.

Object-oriented POV shots are rare in film, and rarer still in title design. Notable examples of object-POV-shot title sequences include 1988’s The Naked Gun, featuring a wailing police siren on the loose, and 1993’s So I Married An Axe Murderer, featuring a giant cup of coffee weaving through a café.

—Yann BlondelSpacecraft, monsters, blowing up cars… all that’s cool but it’s kind of straightforward. Here, all the team was afraid to ruin an amazing idea.

Stills from the main title sequences of 1988's The Naked Gun (left) and 1993's So I Married An Axe Murderer (right), both of which feature object-POV-shots

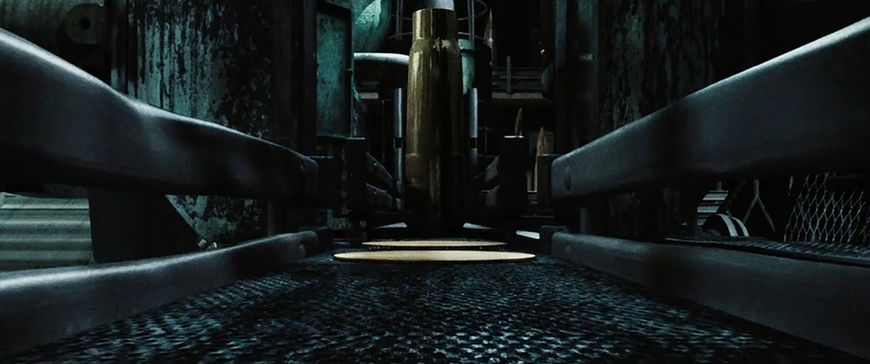

Here, the object is a 7.62×39mm bullet, born in a Soviet Union munitions factory, packed into a crate, shipped over land and sea into a warzone in Africa, loaded into an AK-47, and shot into the head of a child soldier. Placing the viewer in the position of the bullet is startling as well as enveloping. It’s like a finger pointing back, making us complicit, implicating us in the events that unfold for our entertainment. It’s a message so transparent as to be glib, while foreshadowing the climax of the film.

The typography design, angular and clinical, comes care of title design powerhouse Imaginary Forces. It reinforces the detached calculation and cool efficiency of the factory environment and transport journey. The accompanying song, Buffalo Springfield’s “For What It’s Worth (Stop, Hey What's That Sound)”, plays in cocky opposition to the subject matter. The song was written by Stephen Stills after the Sunset Strip curfew riots in Hollywood, California in 1966 and quickly became a well-known protest song, capturing the general unease spreading across America in the late ’60s, becoming an anthem surrounding civil rights and the Vietnam War. The use of the song in Lord of War’s titles gives the opening a warmth and sense of humour that is otherwise absent on the cold conveyor belt of weapons manufacturing. Much like the opening of Dawn of the Dead (2004), which uses Johnny Cash’s “The Man Comes Around”, the sequence’s horrifying visuals gain levity and texture through powerful music.

The sequence is a bold and self-assured overture that cleverly depicts the main thrust of the film, asking difficult questions and packing a punch that lingers long after the end credits roll.

A discussion and visual effects breakdown with Lord of War Visual Effects Supervisor YANN BLONDEL.

Where did the idea of this opening come from? What were the initial discussions like?

Yann: Andrew Niccol had the original idea. The “food chain” idea. It came from Andrew’s brilliant mind. I remember saying that even if we screw it up the sequence will still be brilliant!

Lord of War (2005) main titles DVD commentary with Director Andrew Niccol

Yann: That said, we felt the pressure: spacecraft, monsters, blowing up cars... all that’s cool but it’s kind of straightforward. Here, all the team was afraid to ruin an amazing idea. What we needed was to keep the core spirit of the sequence. Also, it was a long sequence. A modification in one part would generate modifications in all the following parts.

Was there any mention of other opening titles that use a POV shot, such as The Naked Gun?

Yann: Nope! But we’ve studied it.

The Naked Gun: From the Files of Police Squad! (1988) main titles, designed by Douy Swofford

Can you detail your process for creating this title sequence, step-by-step?

Yann: When we read the script we started by requesting a storyboard. Starting from there, we built a previz. Once Andrew was happy with it we started to think how to achieve it. Panicked a little bit! Put ourselves together and used a previz to simulate the elements that we needed to shoot.

In a certain way we used CGI to generate a “false” shooting. Then, we used these elements to be sure shooting this way will work. Well, that worked 75% of the time!

I did principal photography with Bruno Sommier and when it was time to shoot the opening title, [CGI Supervisor] Laurent Gillet joined the team and we both supervised the shooting of the sequence. In all the multiple situations we encountered he was a tremendous help. Laurent and I are old pals.

Was the music in place when you started – “For What It’s Worth”? When did that song come in?

Yann: The music wasn’t there when we started to work on the sequence. Maybe Andrew had it in mind, but when we worked on the previz we didn’t use this track.

First, we begin with a dive toward a machine. Can you talk about how that worked?

Yann: Jean Vincent Puzos, the production designer, and his team built us half of the machine. It’s the way we like to work: cooperation between all film departments. It usually gives good results. We created the rest of the machine and all the moving parts.

—Yann BlondelThe process of building a bullet is insanely complicated! So it was more about telling the story than being accurate.

Yann: We had to build it from scratch using CGI. No elements were shot. We studied factories but people working at bullet factories might find it incorrect. The process of building a bullet is insanely complicated! So it was more about telling the story than being accurate.

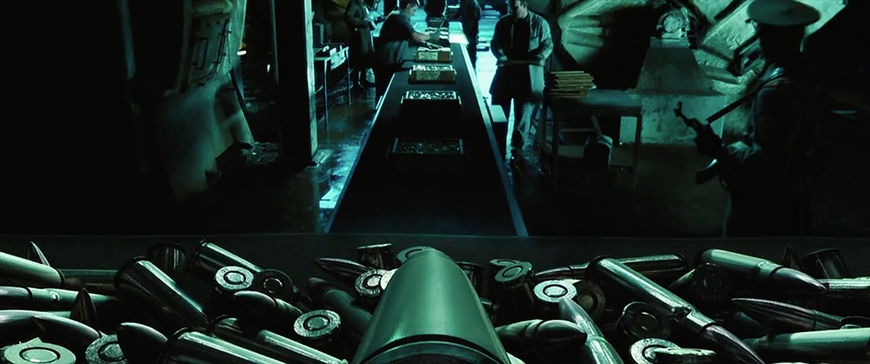

When we move onto the conveyer belt, what’s CGI and what was shot in-camera? How did you achieve the stability of this shot?

Yann: Half of it is CGI. The rest is basically shot in-camera and re-projected on CGI volumes. It was then easy to create an ideal and stable camera.

We shot the head, the hand, and the conveyor separately. We had some nightmares with the positions of the hand. Ran in circles a couple of times! Figured it out. The previz was very useful and a document we kept referring to, even while shooting.

Yann: The tube and box of bullets were entirely CGI. The second conveyor belt was shot and we “just” added our box of bullets. We fixed a couple of things but the background is basically live elements.

How did you match the foreground CG elements with the backgrounds?

Yann: Nowadays it’s pretty easy to match CG elements with the background: you shoot an HDR environment – using bracketed exposures of fisheye lenses or mirror balls – and you use it to light your scene. If everything has been properly calibrated your CGI will match the background. But it’s like bringing an actor onto a pre-lit set. You still need to light the actor to make him or her look good. Same thing with CGI! You’ve got your environment but you need to light your character or object to make it look good.

Well, I digress! We didn’t use environments that much at this time. The light was recreated by hand. A difficult task for talented minds.

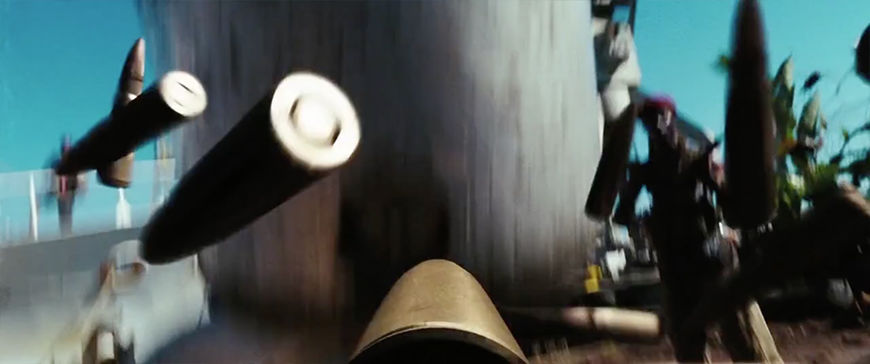

Yann: I’d like to speak of the harbour part a little, too. During preparation we realized that in order to have the point of view of the camera at ground level we will need to shoot with a mirror. Which was nightmarish with the movements we’d planned and would create difficulties later – the image would be somehow a bit distorted and it’s complicated to work with when you use CGI – so we decided to shoot as close to the ground as possible. The whole scene was created in CGI and live elements were reprojected on the CGI. We were able to lower the camera and generate the rolling like we wanted.

—Yann BlondelDuring preparation we realized that in order to have the point of view of the camera at ground level we will need to shoot with a mirror. Which was nightmarish...

Can you talk about the scenes inside the truck when the bullet is being transported?

Yann: It’s basically a camera installed on a crate with people carrying it. We added CGI bullets and voilà! Then when we “dive” amongst the bullets that is 100% CGI. It’s roughly the same principle until we – “the bullet” – fall on the ground, which is 100% CGI.

How did you create the scene where the bullet is being loaded into the magazine and the AK-47?

Yann: We realized pretty early that we won’t be able to fit a cinema camera inside the magazine of an AK-47! So everything is CGI. We thought of building an oversized one but building it in CGI was cheaper. The hand was shot but nearly completely reconstructed and “replaced” by CGI to allow us to push our CGI bullet inside our CGI AK-47.

—Yann BlondelWe realized pretty early that we won’t be able to fit a cinema camera inside the magazine of an AK-47! So everything is CGI.

How did you work with Imaginary Forces and their typography design?

Yann: We delivered the sequence and they added their cards. I believe they created it for the film. A pretty fine and sensitive work, if you ask me!

I must add that Zach Staenberg, the chief film editor, was a tremendous help during post production.

Did you have to shoot any elements yourselves, like green screen or specific textures?

Yann: Nope. Amir Mokri, the DOP, used 35mm to beautifully shoot all the elements of the sequence – like the rest of the film. At that time we didn’t have “prosumer” cameras available. Shooting elements ourselves was a big deal. It’s something we like to do now, getting out and shooting elements.

What tools and software did you use? Would you do anything differently today?

Yann: Softimage|XSI was our main CGI Software. It was rendered using Mental Ray and composited using good old Shake. Today I’m still not entirely satisfied with the final result and sometimes I want to talk to the producer to remake it!