Lars Von Trier’s Melancholia is a meditation, a cri de coeur, and a science-fiction character study that bends time and space. Much has been made of the film since its release in 2011. From its infamous entry into the public consciousness at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival press conference when Von Trier said he understood Hitler to Kirsten Dunst’s Best Actress win at that same festival, to the film’s eventual wide release at the end of 2011, it was immediately recognized as one of the most in-depth and sensitive portrayals of depression on screen, one of Von Trier’s most common themes.

For the bulk of the narrative action, Von Trier favours a handheld, kinetic style of shooting, similar to the rest of his oeuvre, as if the camera is invading the characters’ lives at their most vulnerable.

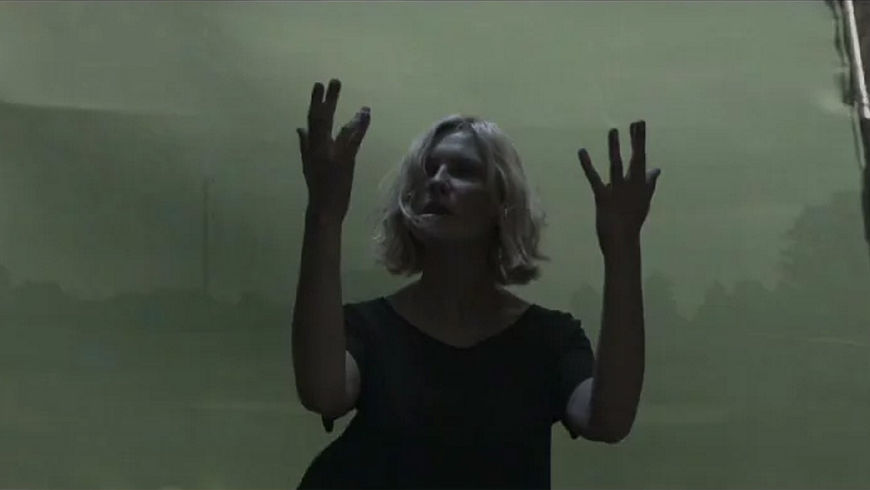

Still from Melancholia showing Justine (Kirsten Dunst) in the bath during her wedding celebrations

The film’s opening overture is presented in contradistinction to this and is made up of stylized images moving in slow motion; they are highly staged and speak to the characters’ inner turmoil and the larger narrative themes that each imbues. An overture, heard most notably before a ballet or opera, previews the score, mood and atmosphere and gives the audience a sense of what’s to come, preparing them for the story. Using the prelude of Richard Wagner’s 1865 opera Tristan und Isolde, Von Trier and cinematographer Manuel Alberto Claro create a kind of mixed-media messaging, blending images from classical art, recognizable stars and one of the most famous pieces of instrumental music with allusions to theatre, religion and the Hollywood disaster film.

Von Trier is fond of the filmic overture, having previously used it in Dancer in the Dark (2000) and Antichrist (2009) to situate the audience inside the emotions of his characters. In Dancer in the Dark, abstract images hint at the main character’s deteriorating eyesight while Antichrist opens with intimate love-making marred by death. Many other films have used the overture, particularly those of the 1960s, including musicals West Side Story (1961), My Fair Lady (1964) and Oliver! (1968) as well as dramas such as Lawrence of Arabia (1962), Cleopatra (1963), and 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

The overture provides glimpses into these two psyches with each sister occupying varying spaces within the frame, filling them with longing, fear and beauty.

Still from Melancholia showing Claire (Charlotte Gainsbourg), John (Kiefer Sutherland), and Justine (Kirsten Dunst) gazing at the sky

Broken into two parts, Melancholia follows sisters Justine (Kirsten Dunst) and Claire (Charlotte Gainsbourg). Part 1: Justine focuses on Justine’s lavish wedding celebration and her slow descent into crippling depression. Part 2 follows the anxious Claire, who is trying to support and care for her sister while navigating the impending arrival of the planet Melancholia. The film’s power is in how it situates the end of the world within the immediate and personal for these two sisters. Justine’s laconic depression, which manifests itself in multiple ways throughout the film, seems to provide her some clarity and peace while Claire’s anxiety and desire for life consumes her. The overture provides glimpses into these two psyches with each sister occupying varying spaces within the frame, filling them with longing, fear and beauty.

Melancholia is the second film in Von Trier’s Depression Trilogy which began after the director grappled with clinical depression from 2006-2007. As he emerged from that, he made Antichrist, Melancholia and Nymphomaniac (2013) which all star Charlotte Gainsbourg as a woman suffering, in extreme and different ways. His inspiration for Melancholia came from his learnings through treatment:

Lars von Trier discusses Melancholia and his persona non grata status in this 2011 interview with IndieWire.

“The film is based on psychologists’ findings that in a crisis like the one in the film, a melancholic person would act in a more practical manner, because they’ve been there before.”

The overture sequence was envisioned by Von Trier but executed by several teams across Europe. Visual Effects Supervisor Peter Hjorth began work on the project early, having already collaborated with Von Trier on Dogville (2003) and Antichrist. Hjorth helped shape the opening sequence, designing the shots and working with Von Trier and Claro to storyboard the overture. Hjorth captured images of the moon and the northern lights to layer into the opening and throughout the film.

—Katarzyna Jarzyna, Visual Effects Supervisor at PlatigeWe were not hunting for typical visually rich, spectacular beauty shots but more for some subtle interesting pictures

SUPPLEMENTARY: Visual effects breakdown with Melancholia VFX Supervisor Peter Hjorth

Ultimately Hjorth and his crew shot the opening sequence with high-speed cameras, the ARRI Alexa and Phantom HD Gold, capturing the actors, objects and backgrounds separately. Then Platige Image, a visual effects studio in Poland, created composites that were sent back to Hjorth and the creative team for notes and approval. Platige’s in-house visual effects supervisor Katarzyna Jarzyna said of the process:

Read an interview with visual effects supervisor Peter Hjorth, as well as Platige Image and Pixomondo, about how they brought a subtle and artistic feel to their effects work on FXGuide.com.

“The trick was that we were not hunting for typical visually rich, spectacular beauty shots but more for some subtle interesting pictures that would tell their own story. It was a lot of experimentation and work back and forth. Thankfully we did have Peter on board who was supervising all the shots in the show and was a link with the director and his strong and precise vision.”

As Von Trier carefully places and executes these slow moving vignettes deliberately to create his overture, they should be discussed in a similar fashion:

Justine, an introduction

The film opens with a close-up on Kirsten Dunst’s face, brimming with a resigned sadness. As her head tilts in slow motion, Wagner’s music begins to crescendo and birds fall from the sky.

The image is disarming, the birds almost look like leaves until their shapes become clearer. It recalls the Bible’s Zephaniah 1:3, which reads:

"I will sweep away both men and animals; I will sweep away the birds of the air and the fish of the sea. The wicked will have only heaps of rubble when I cut off man from the face of the earth," declares the Lord.”

This image, an international film star gazing back at the audience and nature being overturned, is discordant and immediately displaces the audience.

Estate grounds

The film moves to a landscape shot and a large estate featuring a golf course and eerie double shadows. At the forefront of the shot is a large sundial, a pseudo-Doomsday Clock highlighting the importance of time from the outset. In the background two figures can be seen playing, most likely Claire and her son Leo (Cameron Spurr) whom she spins around like the Earth on its axis.

Hunting

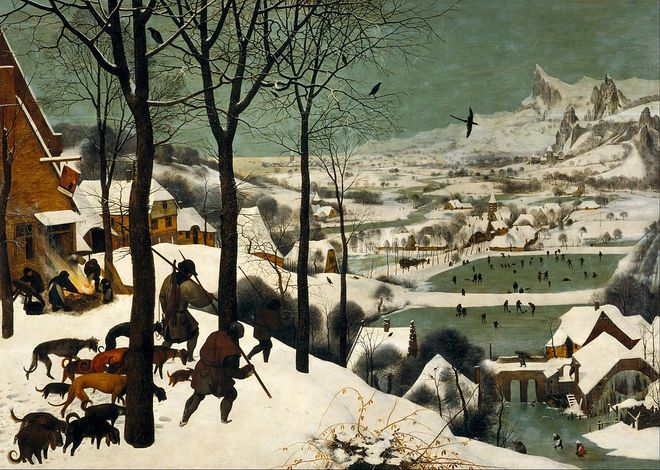

A still shot of The Hunters in the Snow by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, painted in 1565. The painting slowly burns while on screen, hinting at the physical destruction of the Earth.

The Hunters in the Snow also known as The Return of the Hunters, is a 1565 oil-on-wood painting by Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

The painting originates from Early Modern Europe, generally defined as a period beginning around 1450 and lasting until the French Revolution or the Industrial Revolution in the late 18th century. This was a time of advancement in areas including banking to democratic politics to technology. The old world was disappearing.

Bruegel was attempting to capture the beauty and romance of tradition and humanity’s dependence on the natural world. Likewise, Justine’s knowledge and power is tied to the natural world but her intuitions are disregarded throughout the film.

Later, the painting reappears when Justine rearranges the books on display in the house’s library during her wedding celebration. She places the book at the front of the shelf, giving it prominence.

Melancholia approaches

The camera pulls back through space to depict the planet Melancholia heading towards Earth. In Von Trier’s overt use of CGI for this effect he demonstrates that he is not mixing metaphors – a planet is indeed on its way towards Earth. The use of special effects invokes a sense of the popular disaster film, investing in the illusion to make the threat as real as possible.

Mother and son, a sinking feeling

Von Trier returns to the hauntingly absurd with an image of Claire carrying Leo through the golf course, her legs sinking into the ground. It’s a nightmarish image which highlights the desperation of a parent to save their child. The image also speaks to Claire’s paralysis later in the film as she becomes overtaken by fear during the climax, too bereft to be of use.

Descending horse

A horse falls slowly. Horses figure throughout the film as the estate houses several of them in the stables and Justine often goes riding. The horses become vessels for the sisters’ emotions, becoming part of key character moments. Riding Abraham, a horse perhaps named after the biblical figure who tried and failed to bargain with God to spare Sodom and Gomorrah, is one of the few activities that cheers Justine up. Later, Justine takes her frustration out on the horse, violently beating it when it refuses to leave the estate grounds. Similarly, when Claire finally realizes the truth of their impending doom, she frees the horses.

Bugging

Justine faces the camera, arms outstretched as insects fly around her, recalling imagery in the Bible such as the swarms of locusts who destroy crops. By standing in the midst of the swarm, Justine appears impervious to them.

Wedding attire

In the next segment we glimpse the central characters in their wedding finery. They stand in front of the estate with Melancholia, the Moon and the Sun looming large in the sky, Justine underneath Melancholia, Leo under the Moon and Claire under the Sun. These placements speak to the characters’ own relationships with each other and the Earth. Justine is an outside influence on the family unit and a natural force of destruction; Leo remains passive throughout the film, a smaller entity, unable to act but tethered to a larger body; and Claire, the nurturing force, panicking at the realization that there will be no life left, nothing left to grow. As Claire and Justine discuss:

Justine: The earth is evil. We don't need to grieve for it.

Claire: What?

Justine: Nobody will miss it.

Claire: But where would Leo grow?

Melancholia grows closer

Von Trier repeats the CGI instance of Melancholia advancing on Earth, the planets obscuring each other, foreshadowing the twist in the planet’s trajectory in the film’s climax.

Electric ladyland

A medium shot of Justine as electricity shoots from her fingers, alluding to the various atmospheric disturbances that occur when the Earth’s magnetic field is breached and to Justine’s relationship with the planet. It also references the name of the character, which Von Trier has said comes from Justine, or The Misfortunes of Virtue by the Marquis de Sade. In the novel the hero Justine is cast aside throughout her life, repeatedly and violently brutalized. Though she is to be executed at the beginning of the book, Justine’s account of her story to a woman who turns out to be her long-lost sister saves her. She becomes morose and withdrawn, however, after her life is spared and is fatally struck by lightning. In this moment Melancholia’s Justine is not spared death but she appears untroubled by the lightning, drawing power or peace from Melancholia’s approach.

Walk down the aisle

Justine, in her wedding dress, strides across the lawn. She is weighed down by vines emerging from the earth, entangling her. An arresting image, it doesn’t have the same devastating effect as the earlier shot of Claire and her son sinking into the ground, but there is something powerful about her perseverance in this sequence, alluding to her ability to “know things” and bond with the natural world.

Melancholia grows near

A return to an image of the planet to remind us of impending doom.

The burning bush

One of the many manicured bushes of the lush estate burns as the camera peers through a bay window surrounded by comfortable seating, an allusion to the burning bush in the Bible which God uses to tell Moses to lead the Israelites out of Egypt. But here, there are no living things (human or animal) who bear witness to the bush on fire. The room is empty and the grounds are still.

Reviving Ophelia

In perhaps the most iconic image from the film, Justine is shown in her wedding dress, bouquet in hand, floating in a stream. The image recalls Sir John Everett Millais’ 1852 painting Ophelia which depicts the last moments of Hamlet’s love interest, who drowns herself.

Ophelia is a painting by British artist Sir John Everett Millais, completed in 1851 and 1852. It depicts Ophelia, a character from the William Shakespeare play Hamlet, singing before she drowns in a river.

In Shakespeare's play, Ophelia’s death does not take place on stage but is revealed through dialogue. Similarly, many of the images in Melancholia’s overture do not take place in the film but rather establish and hint at its themes.

Preparation

Justine marches towards the camera as Leo carves sticks. A moment where these two characters take it upon themselves to prepare in some way for the end of the world.

Melancholia arrives

Von Trier has stated that he did not want the end of the film to be a surprise, that the audience should know the world was going to end from the very beginning. In this final moment of CGI, the much larger planet Melancholia collides with Earth, wiping it out of existence.

The last part of the overture is the title card, which stands in stark contrast to the highly-produced, glossy, and emotional scenes presented thus far. The words “Lars Von Trier Melancholia” appear to be inscribed on yellowed paper, the rough text rubbed or scratched out of a swipe of dirt, creating a stylistic pause and bridging the gap between the stylized opening and Von Trier’s handheld camerawork.

Much like the film itself, the overture of Melancholia creates an intimate yet distancing experience as people and planets collide. The end of the world is set to classical music, elements seem familiar but out of place, and the images are beautiful but eerie. Von Trier situates these characters in the larger contexts of art, religion, and celebrity, and embraces humanity enough to ask: Who will we be at the end of the world?

Director: Lars von Trier

Director of Photography: Manuel Alberto Claro

Visual Effects Producer: Karen Maarbjerg

Visual Effects Supervisor: Peter Hjorth

Visual Effects: Platige Image

Visual Effects Supervisor: Jakub Knapik

Visual Effects Producer: Katarzyna Jarzyna

Planet Collision Visual Effects: Pixomondo

Visual Effects In-House Supervisor: Sven Martin

Visual Effects In-House Producer: Sabrina Gerhardt

Lead CG Artist: Max Riess

Visual Effects Artist and Simulations: Pieter Mentz

Compositing Artist: Travis Nobles

Collision Consultant: Dr. René Reifarth, Goethe-University

Credits & On-Screen Web Graphics Design: Lungo, V/Rasmus Lange

Music: Excerpts from "Tristan und Isolde" by Richard Wagner