In the pantheon of goofy, gory and trashy ’80s horror movies, 1988’s Night of the Demons is one of the best. Directed by Kevin Tenney, the movie chronicles the wacky and violent misadventures of a group of ill-begotten teens invited to a Halloween party at an abandoned house by their high school’s token goth weirdo, Angela (Amelia Kinkade). When the gang performs a séance, they accidentally summon a demon. As the hapless teens lose their souls one by one to this party beelzebub, it’s up to the token virgin and her date to try to survive until sunrise.

While Night of the Demons didn’t re-write the ’80s horror playbook, it has likely endured in the memories of horror fans due to some wacky and inventive touches, including a wild fireside possession dance set to Bauhaus and a scene involving a tube of lipstick that reaches John Waters-esque heights of perverse surrealism.

Night of the Demons (1988) trailer

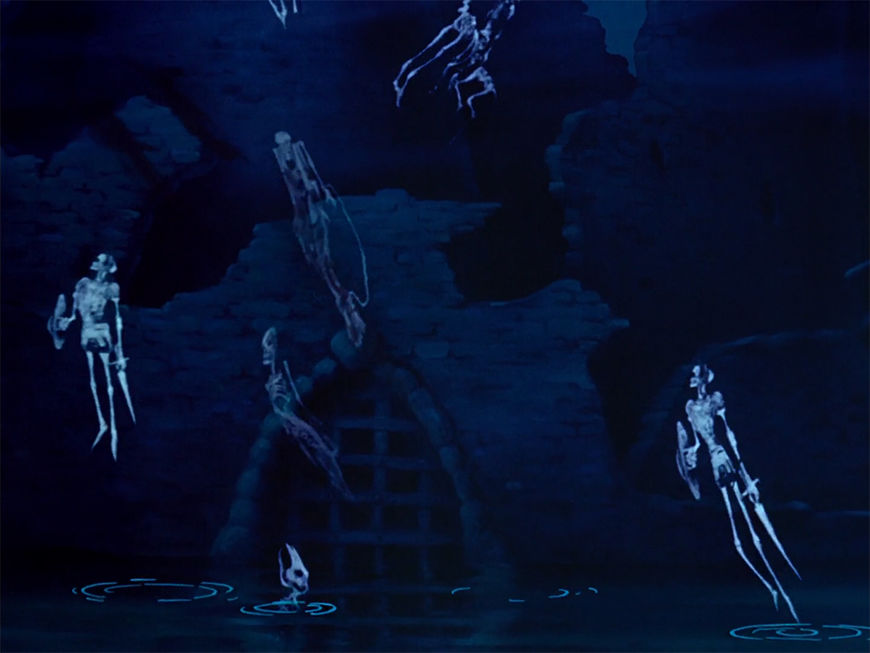

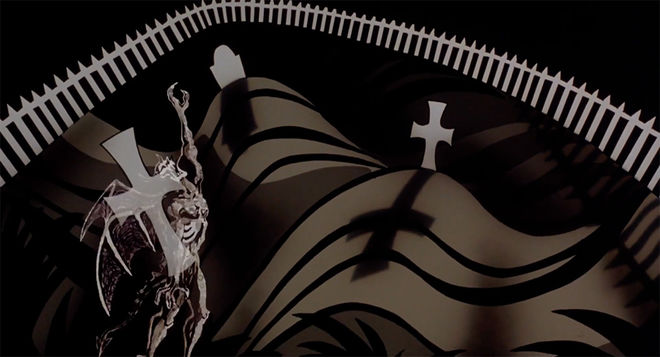

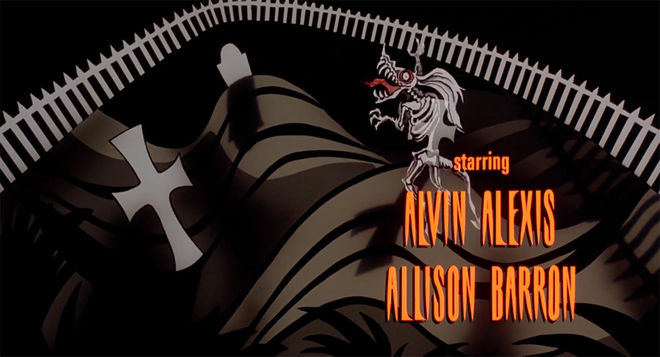

But the movie’s most distinguishing feature is its title sequence by animator Kathy Zielinski: a simple but beautifully atmospheric animated narrative following a clutch of ghosts and ghouls as they rise up black hills to a house to float and haunt and party, set to Dennis Michael Tenney’s ominously propulsive synth theme. The sequence serves as a standalone mini-film: a loving tribute to the dark forces of the night and the various beasties heeding its malevolent clarion call.

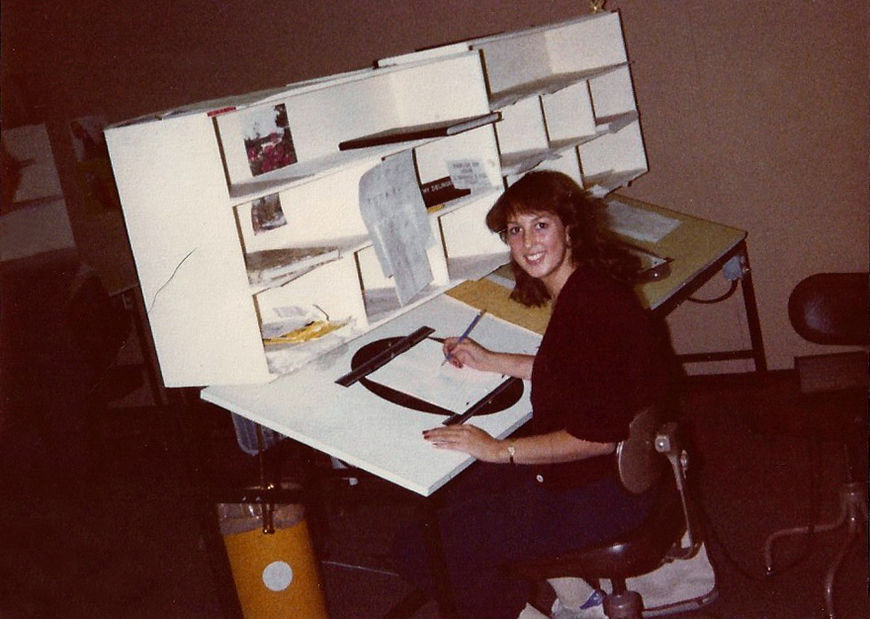

Animator and Character Designer Kathy Zielinski

The sequence also marks a turning point in Zielinski’s career. She embarked upon the painstaking two-month process of designing and animating her first (and only) title sequence while also working on a major gig for Disney studios, animating one of the most memorable cartoon villains of all time: Ursula the Sea Witch from The Little Mermaid (1989). She went on to work on some of Disney Studios’ biggest films, including Aladdin (1992) and Frozen (2013), and at Dreamworks Animated Studios before making a foray into 3D animation with films like Kung Fu Panda (2008) and eventually returning to hand-drawn animation in her current gig on The Simpsons.

The NOTD sequence remains a significant high point in Zielinski’s 30-year career, establishing a gleefully mordant love of darkness and villainy that has marked many of her biggest projects.

Zielinski’s appreciation of the macabre and infernal was first stoked in her early teens, in a darkened movie theatre in her hometown of Torrance, California, during a screening of one of the great hallmarks of Disney animation: Fantasia (1940). While everyone else roared about Mickey Mouse and the cavorting broomsticks of “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice,” Zielinksi was enthralled by the movie’s final segment: "Night on Bald Mountain."

Still from the "Night on Bald Mountain" segment of Fantasia (1940), featuring Chernabog

In what was then considered Disney’s most “grown-up” animated film, "Night on Bald Mountain" is perhaps the darkest and least conventionally child-appropriate segment of them all, taking viewers into the depths of Hell itself. Scored to composer Modest Mussorgsky’s eponymous piece, "Night on Bald Mountain" opens with the titular mountain, rising black and monolithic in a torpid sky. The mountain unfolds its wings and a giant head rears upward. The mountain is a demon called Chernabog. In Slavic languages, the name “Chernobog” literally means “black god”: in the context of the film, he’s the god of evil. His glowing yellow eyes appraise the village below, and he raises his arms, summoning a host of ghosts, dead warriors, demons, hags and harpies.

Still from the “Night on Bald Mountain” segment of Fantasia (1940), featuring Chernabog

Stills from the “Night on Bald Mountain” segment of Fantasia (1940), featuring various ghosts summoned from their graves

The ghosts swirl around Chernabog as he starts a giant fire, and soon he’s surrounded by a wild bacchanal – a celebratory dance of death and flames.

Still from the “Night on Bald Mountain” segment of Fantasia (1940), featuring Chernabog's face and flames

Alas, the spell is soon broken – this is a Disney movie, after all – and a heavenly dawn begins, set to Franz Schubert’s “Ave Maria.” Dismayed, Chernabog raises his arms imploringly to the brightening sky, folds his wings and slumps back into the mountain. The ghosts and ghoulies return to their graves and to the sea. The sky is lit with soft blue and a series of lights carried by monks: all is holy, all is well.

Still from the end of the “Night on Bald Mountain” segment of Fantasia (1940) during which "Ave Maria" is playing

Still, the frightful image of Chernabog, brought so vividly to life by a team led by legendary animator Vladimir "Bill" Tytla, was burned into Zielinski’s memory.

“Chernabog was my favourite part,” says Zielinksi. “I remember always drawing him, the villainous characters. I had a small poster on my wall. I always liked monsters.” Zielinksi’s affinity for giant monolithic beings extended to her taste in horror films and a lifelong preference for villains over heroes: “I watched a lot of Japanese monster movies,” she says. “I wasn’t much into comic books. I loved Godzilla, Mothra, the Gargantuas. I watched a lot of giant robots, too. Dracula, Frankenstein, all that stuff.”

A teacher encouraged Zielinski to apply to the animation program at the California Institute of the Arts and she was accepted in 1979. She was one of only a few women in her classes, and by her second year all the other women had dropped out.

Kathy Zielinski at the California Institute of the Arts, 1979

“My sophomore year film was called Guess Who’s For Dinner? and it was about a spinach monster that ate a kid at dinner time,” she remembers. “[My teachers] were a little surprised that I had that desire to make more of a stronger evil film. I think that they thought that I might like to animate something more ‘girly.’ But I always liked villains and evil stuff – I think it surprised them.”

The film went on to win a student Academy Award, and Zielinski was hired by Disney in 1981. Her early jobs included clean-up on movies like Mickey’s Christmas Carol (1983) and The Black Cauldron (1985), as well as character design work in Oliver and Company (1986).

Ursula from Disney's The Little Mermaid (1989)

Then came The Little Mermaid and its Ursula – everyone’s favourite lascivious, curvaceous villainess. Modelled on the queen of camp cult, Divine, Ursula’s fluid and oily movements are some of the best things about her, slinking along the ocean floor, all cleavage and tentacles. Zielinksi watched Sunset Boulevard (1950) to absorb Gloria Swanson’s flamboyance for the character. She was tasked with a number of aspects of the character animation – the first conjuring sequence, as well as the reverse transformation of Vanessa, Ursula’s raven-haired alter ego.

Ursula and her alter ego Vanessa from The Little Mermaid

At this time, Zielinski was dating her future husband, FX artist Kevin Kutchaver. Night of the Demons’ line producer Don Robinson was looking for an artist to create an animated title sequence for the film. Zielinski and Kutchaver were recommended through a mutual friend – Zielinski for the art and Kutchaver to film it.

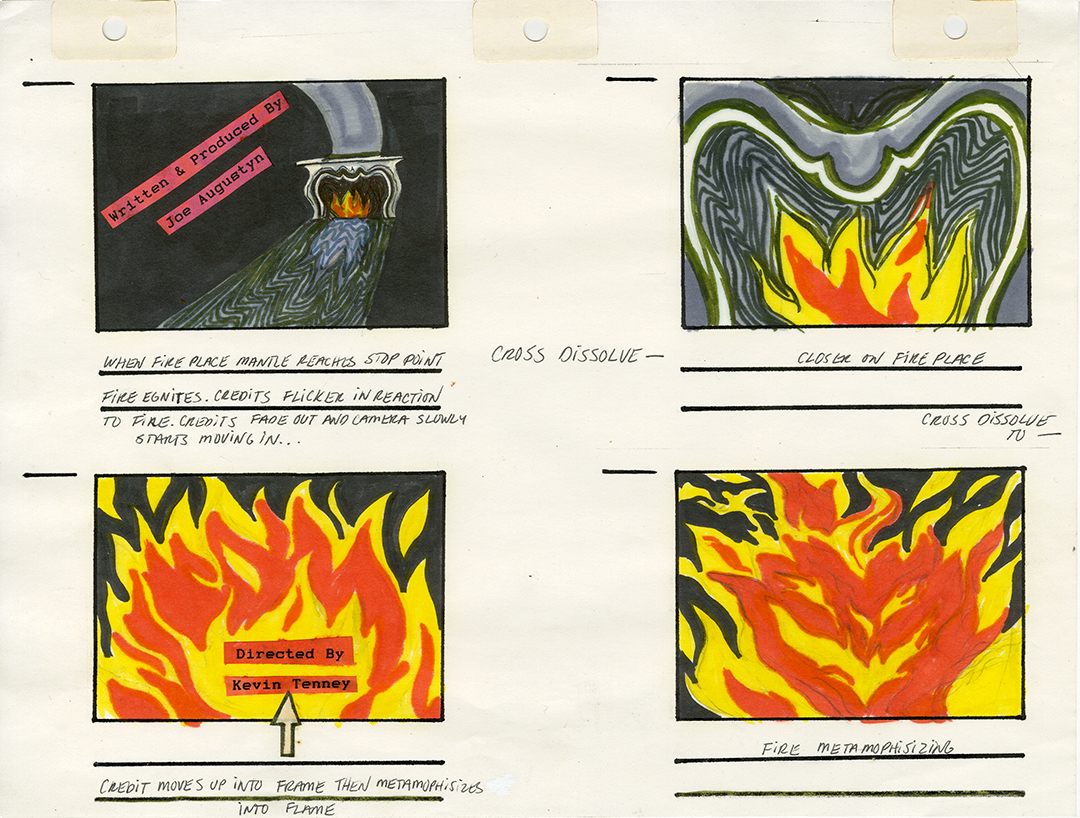

According to horror lore, director Kevin Tenney was originally hesitant to spend some of his meagre budget on an animated opening. “It was such a low-budget film that of course, understandably, he might want to use that money for other scenes or other reasons,” Zielinksi says. “I went in and I met him, and once I showed him my art, what could be done, and I did some storyboard drawings, that’s when he was convinced.”

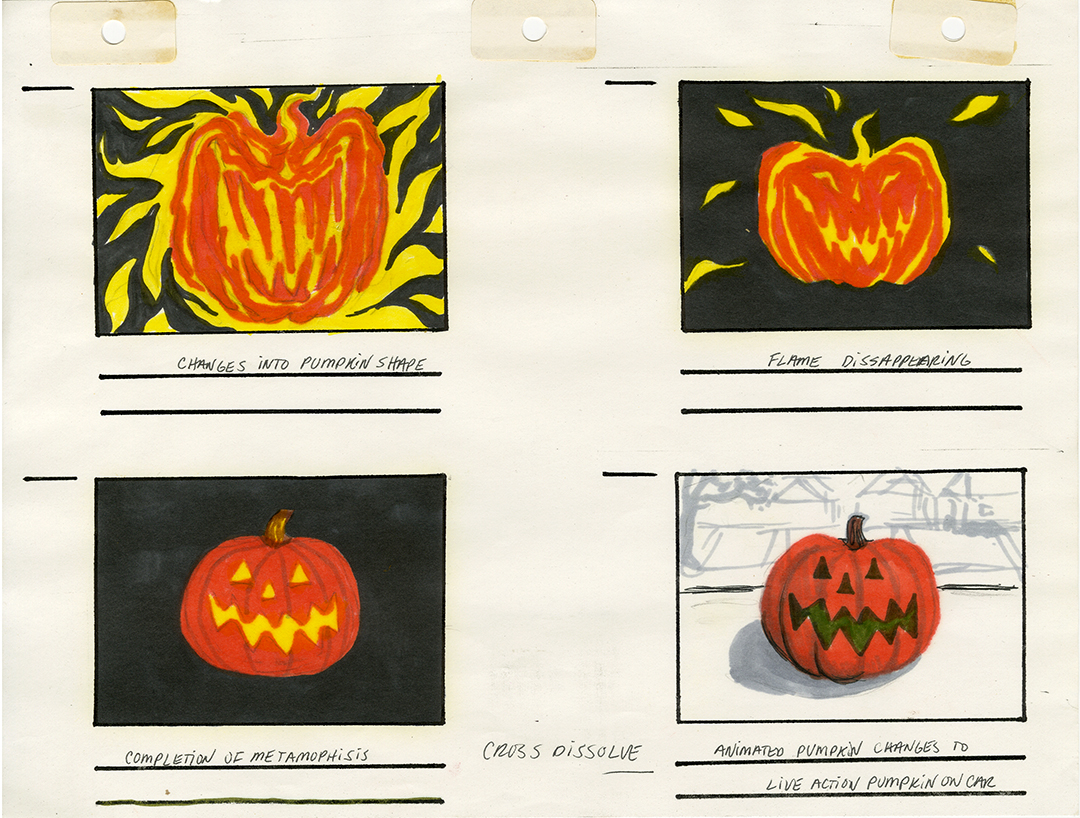

Storyboard panels by Kathy Zielinski for the title sequence of Night of the Demons

Storyboard panels by Kathy Zielinski for the title sequence of Night of the Demons

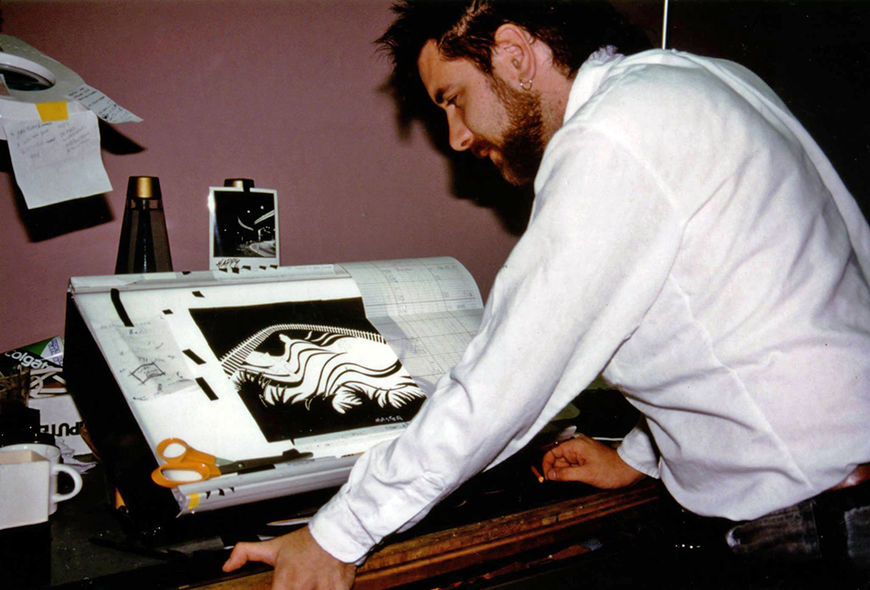

Creatively, Zielinski was given remarkable leeway. Tenney provided the script and five title cards that needed to be included and the rest was up to her. With Kutchaver she embarked on a painstaking process that involved partial animation and filming of cutout figures using an Oxberry camera, the same type of camera used to shoot "Night At Bald Mountain." Kutchaver borrowed the Oxberry from the set of Superman IV, where he was working as a visual effects animator.

“A lot of the choices were made because of budget,” Zielinski says. “That’s why there isn’t a lot of what we call ‘full animation.’ Most of it – especially the ghosts coming out of the graves going up the hill to the house – was cutouts. [Kutchaver] would take my drawings and figure out how to put it together. A lot was shot under-camera, combining different camera moves. The hill coming into view with the ghosts running up, that was pretty difficult to figure out.”

Stills from the Night of the Demons title sequence featuring ghosts emerging from their graves

Zielinski had clear plastic cels, drawn upon and painted, and Kutchaver exposed those elements within the camera. Most of the sequence was shot in-camera with the addition of certain animation elements: for example, the shadow that moves stealthily up the wall inside the house, the crackling fire in the fireplace, and the pumpkin animation going into the live animation. The process involved shooting multiple elements (the ghosts, the hill) and rewinding the camera manually. “It’s crazy that it was all done in-camera like that; it takes a lot of planning versus what they would do today, which is just do it optically and film all the different layers and then composite them,” Zielinski says.

Kevin Kutchaver, who executed the shooting of the animation, with Kathy Zielinksi's Night of the Demons artwork

The process took about two months. Zielinksi was working long days at Disney animating Ursula and then would come home to her personal animation studio to work on the title sequence. Meanwhile, Kutchaver would pull similar late hours on the project after working all day on Superman IV. The idea of pushing oneself to the limit for a title sequence on a low-budget, schlocky horror movie might seem like folly to some but Zielinski laughs: “I did it because it was cool!”

“I love horror, and at Disney, even though I got to do a villain, I got this extra edge of creativity, that I was creating, that wasn’t for Disney or anything,” she recalls. “It was in my own style, so that was fun to be able to do that, come up with stuff from scratch.”

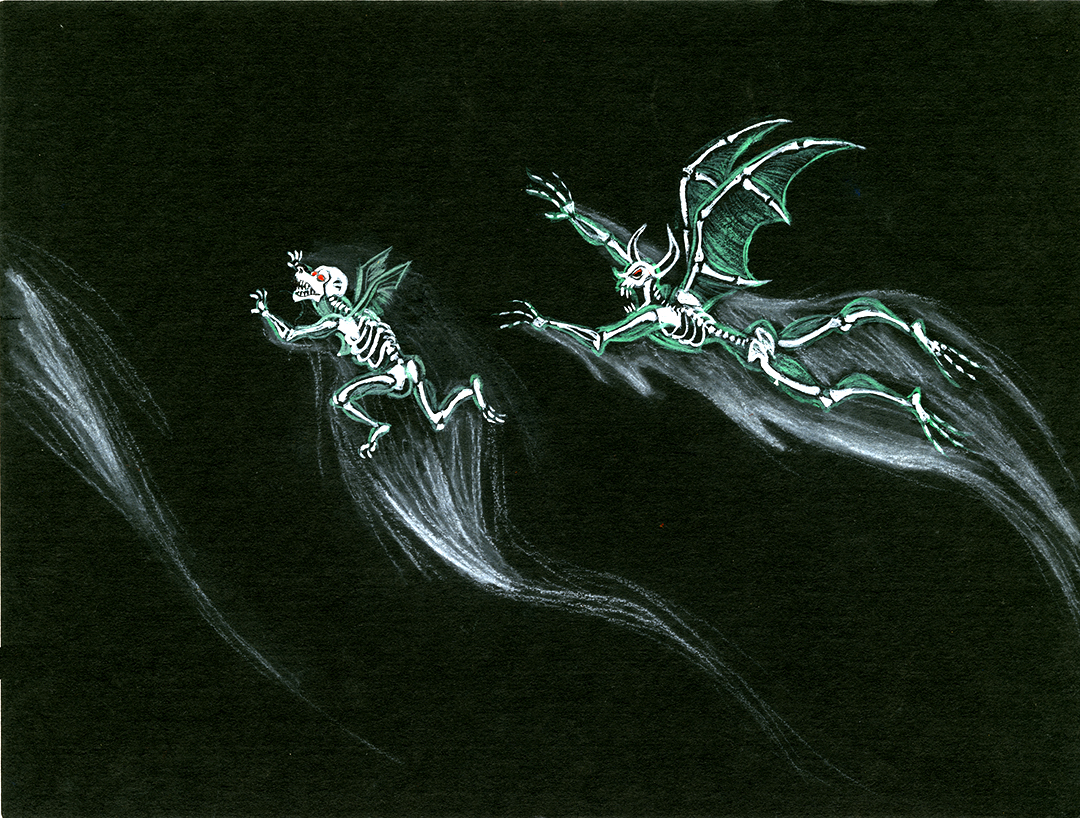

Early design sketch by Kathy Zielinski featuring ghostly demons

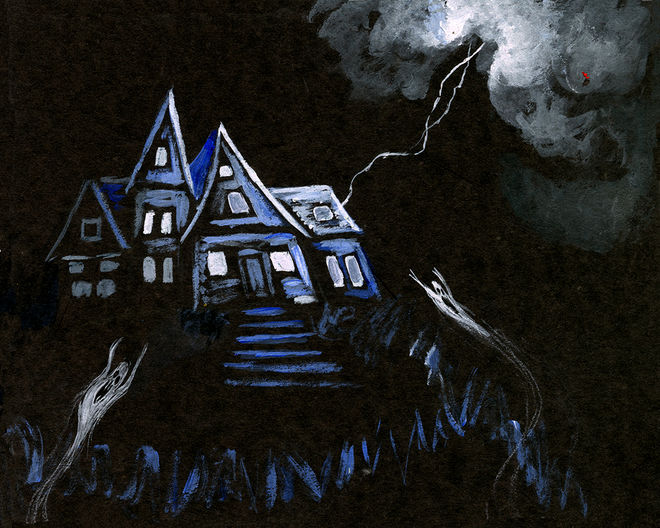

Early design sketch by Kathy Zielinski of haunted house

The style and tone of “Night at Bald Mountain” is woven inexorably into the fabric of Zielinksi’s title sequence, from the cutout/Oxberry techniques to the rising monolithic black hills that summon the ghouls from their graves. “You can tell I was very inspired by ‘Night at Bald Mountain,’” Zielinski reflects. “I can’t say that I wasn’t. You’re panning to that pinnacle moment at the top of the hill, where instead of Chernabog, I have the house.”

What distinguishes Zielinski’s style is how playful it is. Her version of the house’s fireplace is off-kilter and stretched to surreal angles, with glowering red eyes, and the ghosts themselves – the skeletal bats, the mohawked demons – have a delicate and thrilling animism. At one point, a ghost by a window seems to sigh and turn into a shredded curtain. The pumpkin leers in brilliant orange. For a piece that celebrates the dead, it seems so deeply and wholly alive.

Zielinski never made another title sequence but the delicacy and liquid movement of her Night of the Demons opening lives on in many of her higher-profile creations: Ursula’s tentacles, Jafar’s eyes glowing pumpkin-red as he transforms into a snake at the end of Aladdin, or the dancing/dripping scenes of Hexxus, the liquidly malevolent embodiment of pollution voiced by Tim Curry in FernGully. Like Chernabog, she’s conjured up the most gleeful and lively dark creatures, bringing them to us in thrilling colour and life to dance before our eyes – again and again.

Animated Title Sequence by: Kathy Zielinski

Animated Title Photography: Kevin Kutchaver

Music: Dennis Michael Tenney