Since it debuted in 1986, Pee-wee's Playhouse, the loony, bewildering cloud cuckoo-land of a television show, has been hard to describe in the finite terms of our known world. Even after ample introduction to Paul Reubens' living firecracker character through a stage show, an HBO special, and Tim Burton's directorial debut Pee-wee's Big Adventure, the TV series felt like something holistically new, remarkably unlike anything before it. Dinosaurs live in the walls and every piece of Pee-wee Herman's furniture is alive. There are always new secrets to explore, more cartoons to watch, and fresh wishes to make. It was a colourful compendium of Saturday mornings, a part of your balanced breakfast, assuming the other part was a bowl with every sugary cereal mixed together. To quote the show’s loopy theme song, "you've landed in a place where anything can happen!"

So how the heck do you open that?

Coming in from the forest, you float by it all: Stop-motion animals living harmoniously in the groves surrounding Pee-wee's pad. A winking sphinx within earshot of a snowman. An out of control lawn, pink flamingos-style tchotchkes growing into their own Disneyland park. Puppetry, claymation, and whatever you'd call the animation of Pee-wee himself, the introduction to the Playhouse is a lush sensory exploration and explanation of the nonsensical dimension you are entering. And we haven’t even gotten to Cyndi Lauper singing about the kooky residents inside! Magic is here, in spite of mechanics, the motors, pulleys and winches all visible, and decorum creaks like a mechanical sign. It doesn’t make sense! It is a vortex, a mystery, its own anomaly, up is down, down is up, cats and dogs sharing vows. The walls expand indefinitely, which is a requirement since Pee-wee needs all that space to bounce off them.

Pee-wee's Playhouse had a murderers’ row of creatives on-board including artist Wayne White, underground cartoonist Gary Panter, visualists Prudence Fenton and Phil Trumbo, Devo's Mark Mothersbaugh, and even Rob Zombie as a production assistant, with Reubens chuckling at the steering wheel. The production was a sight to behold, a wicked brew of zine bric-a-brac, new wave pop, Bugs Bunny, and roadside mini-putt. A recipe for a beloved children's show, a cult phenomenon, and a legacy that is ready to relaunch itself with a new film helmed by the ridiculously appropriate John Lee, co-creator of Wonder Showzen. The introduction to Pee-wee's Playhouse had to establish all of this creative whimsy in a great sugary gulp of puppets, nonsense, and Pee-wee himself.

We speak to Senior Animation Producer PRUDENCE FENTON, Animation Director PHIL TRUMBO and Pee-wee Creator/Star PAUL REUBENS about the nutty undertaking.

Can you give us a bit of background on how you got involved with Pee-wee’s Playhouse?

Prudence Fenton

Prudence: I worked for a company in the early ’80s called Broadcast Arts in New York City. They were a stop-motion animation company, and they did the MTV IDs then. I think we did 73 MTV IDs. We did all kinds of commercials. We would go to all these agencies and tell them that they were only limited by their imagination. You can make anything fly through the air! You can make inanimate objects come alive! You can make crackers dance! You can make Twizzlers stretch! You could make matches form into houses!

Phil: I was a director at Broadcast Arts. We animated commercials, music videos, and combined all kinds of special effects, stop-motion, motion control, every kind of animation there was at the time. Paul had gotten a contract with CBS to do a kids show, and this talent agency brought us together.

Prudence: Somebody at CBS met with one of our head guys and said they had this very interesting project with Pee-wee Herman. He had his HBO show and CBS wanted to do a show, and wanted Broadcast Arts to do the animation.

Phil: They knew our expertise and they knew what we had done. We were all big fans of Pee-wee’s movies and HBO program. It was a really good match.

Prudence: I was one of the first people brought on to staff it. The way that it was described to me was that this Pee-wee guy would come in, shoot for a couple weeks, but it’d mostly be an animation show. Of course, it wasn’t. He didn’t come in for two weeks, he came in for ten weeks. Paul was very much involved. I think the reason the show was so brilliant was because Paul was the main chief, and all CBS interfered with was just standards and practices. They didn’t rewrite the scripts – it was pretty much raw Paul and his writers.

Phil Trumbo holds the miniature Pee-wee Herman

Phil: We had a meeting with Paul and his producer, it went really well. For the first season it was done in New York City, right near Canal Street. Our studio was right around the corner from CBGB’s, it was at Bleecker on Broadway. It was really the epicenter of a lot of post-punk, new wave art and music. We had access to an incredible talent pool of folks who came on to the show.

It was a real murderers’ row of creative people involved with Pee-wee’s Playhouse. What was it like to assemble that crew?

Paul: Prudence really had the most to do with that. I didn't really select the crew or put the crew together. I did way more after the first one, when we redid it, and when we did it for the Christmas Special. We did it at least two other times.

I'm super spoiled in that I have just had incredible people around me from the get-go. I think it's probably because Pee-wee Herman attracts certain people. Pee-wee's Playhouse added to this, probably even more than my movie, more than other things, but my career's been viewed by many people, including myself, as being arty. [John Lee], the director of the Pee-wee movie that I'm working on now, said to me very early on, "It's great walking into your production office because you can just tell everybody here's a fan of Pee-wee Herman, and it's kind of like, let your freak flag fly." You walk in and you know this is some kind of oddball project because nobody looks like they belong in an office, and that may be true of a lot of show business, but everything that people remember and talk about, about that show, is who all the people were that contributed to it – all being very eccentric, colorful, arty, talented artists.

So, what was the original vision for the opening sequence?

An early sketch of Pee-wee's Playhouse by Production Designer Gary Panter

Paul: The original concept for it was always something that was going to reveal what was inside [the playhouse]. It was the case for everything, the wrapping. So, it's the exterior of the playhouse, which we don't see except in a model at the opening, and I wanted it to be hypnotic. The whole idea of it from concept to execution was something that just sucked you in, that drew you in, that was hypnotic in a way, and made you want to go inside and see what was inside of there. And also, just to immediately change the world, to set up, to dictate the world. I feel like we stuck to what my original vision was.

Phil: It was originally of a much larger scale. It started in outer space, zooming through the planets toward Earth, a stop-motion cartoon version of the universe. Then you pick up on the zoom into the forest, that was originally Ric Heitzman’s vision of it. He did a lot of the design for the exterior of the playhouse. All of the design for that was created rather intricately. I was directing the dinosaur family sequences – the dinosaurs that live inside the wall – and I was working with my wife on some of the ant farm sequences, and I was asked to direct the opening title sequence. I did a lot of storyboards. We started the show in the spring, and it had to be on the air by the fall. We had to cut down the scope of it a little bit.

Prudence: We were going to build the playhouse and fly around outside of it, have an animated Pee-wee walk inside, and once he got inside there would be this introduction to all the puppet friends and so on. The outside opening that we did was supposed to be what you see. You see the beaver chewing down the sign. The tree falls and the camera move starts.

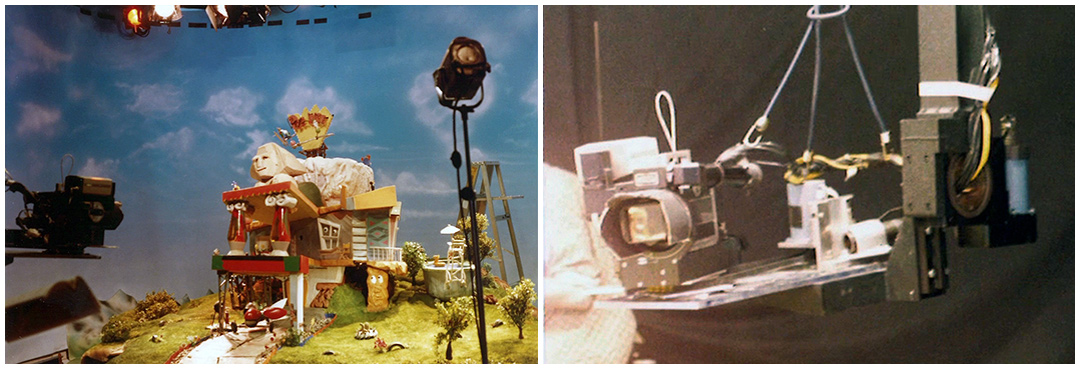

Camera and model set-up for the opening forest scene of the Pee-wee's Playhouse title sequence

Prudence Fenton takes a break during production of the Pee-wee's Playhouse opening sequence, 1986

Phil: Paul really wanted you to feel like you were going into a national park, so the sign has that carved look to it. There’s actually another whole sequence to it that had a forest with deer frolicking around in it, like Bambi, and you’d zoom through this beautiful sylvan glade, with stop-motion deer and stuff running around, then you’d get to the sign saying it’s a national park. Again, we had to trim that down.

I know when I was a kid all I wanted to see was more of the surrounding area, it just seemed like such an infinite and magical world.

Prudence: I remember I kept saying “How come we never go outside? Can’t we go outside?”

Paul: That's why I really want to make the Pee-wee's Playhouse movie. That's the first movie script I ever wrote, and it's the oldest script that was never made, and that's what it is. It shows all the rest of that stuff – outside.

Phil: Yeah, it’s neat. Honestly, what pushed the whole sense of scale of it, was Paul’s imagination. Wanting this combination of things. Paul was very challenging, but you’d always end up with something very interesting. You really felt like you had this expanded universe here, that you could go on forever. It gave you permission to be crazy like a kid, so you’d want to come forth with all that stuff.

Image Set: Building the Playhouse – Mock-ups and scale models of the playhouse were built before construction of the production model began

You have a lot of images that contradict each other in the opening, like the sphinx next to an igloo...

Phil: It’s [the idea] that anything is possible, that you can go from one of those things to another. It’s like a kid looking through National Geographic magazine, and wanting to see an Eskimo on top of the pyramids. That kind of funny juxtaposition of imaginations.

Prudence: It was a visual feast. The whole show was, as it ended up. But I think the opening really wanted to say that. It was a friendly place, with the rabbits and the crickets, pterodactyls. Every kid wants a pool like that. You always want the barbershop pole. You have cake with the icing on top. You know, it was visually delicious.

Image Set: Detail shots of the model used for season one of Pee-wee's Playhouse

Paul: I wanted it to be wacky, and just full of iconic images, things that were mixed into it.

Prudence: Everything about it was designed to seduce a kid into watching it.

Phil: I also think the idea of being diverse, being inclusive, was one of the real themes of the cast and crew of the Playhouse. It was a much more ethnically diverse, sociologically diverse group.

Can you walk us through the production process – what were some of the challenges you encountered?

Prudence: This was early, we’re talking 1985, pre-After Effects, pre-everything, so you have to do all your animation and effects in the camera. today we could probably do that opening in four weeks. Back then, it took four months.

Phil: Our studio on Broadway was an old, large walk-up, a warehouse where we were shooting the live-action footage. It was a converted loft; above us was a sweatshop with small Asian ladies sewing garments. The elevator was so loud – it wasn’t a proper soundstage – and we’d have to stop the elevator service while we were doing sound takes. There was no air conditioning, so eventually we had to bring in one of those trucks from the airport with a hose through the window. It was pretty funky.

The motion control camera rig used to shoot the season one opening of Pee-wee's Playhouse

There was a bit of conflict about the opening, because we had two computer-controlled camera rigs, called motion control rigs. One was huge, it was the size of a railroad track, with computer-controlled cameras on it, and there had been some delays getting the show going, so we had to use a smaller rig that didn’t have quite the same capability. Paul had a specific idea of what he wanted this move to look like – like a helicopter flying over LA. We had to make serious technical compromises to achieve that. I kept showing him and most weren’t what he was looking for. I brought a handheld video camera to the set, met Paul there, and asked him to walk me through what he had in mind.

Paul: We took a video camera and moved it around the model just to sort of get an idea. I can't remember what was wrong with it or why it wasn't working but I remember going: “This isn't it, this isn't it.”

Phil: It ended up allowing him to physically interact with the set and it let me better understand what he wanted. It went through an enormous amount of revisions, to the point where we’d basically shoot black-and-white storyboard animatics of the major set, of what the move was going to look like, before we committed to doing the days of stop-motion animation.

Image Set: Animator Kent Burton animates the Pee-wee Herman figurine for the season one opener

Prudence: The animation studio was two blocks from where the live action was, so it was a matter of walking down Broadway and showing Paul this black-and-white video camera move, and then Paul would make a comment, and every comment he made improved it.We made as many tests as we possibly could, and after seven weeks we were finally ready to shoot it.

Phil: I would run up and down Broadway with my little video. It was the VHS days so I would transfer the film to video. When we had the camera moves we would film those on 55mm film, in black and white, single frame at a time, so you’d have a sense of moving through the set. I had done about 19 versions of that until we had one that we felt like worked for Paul.

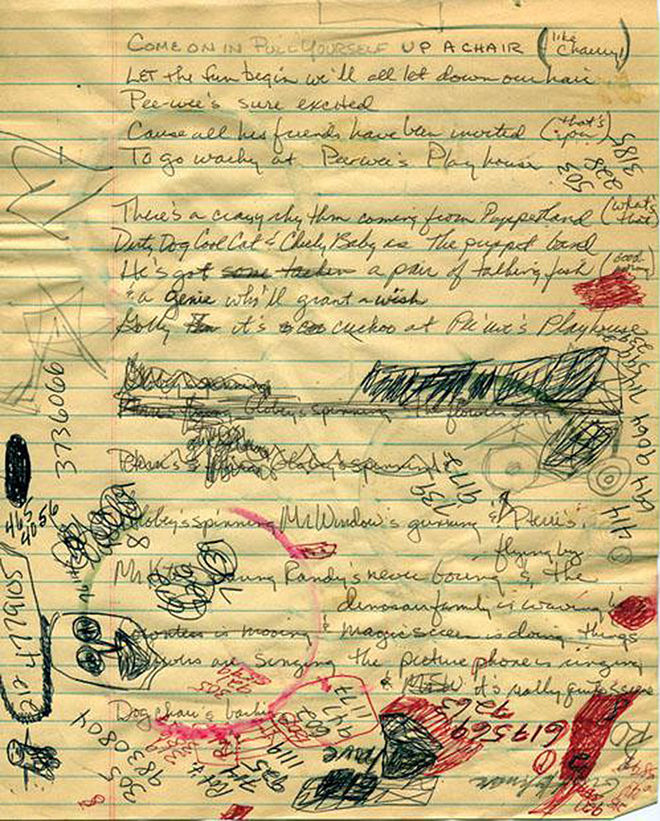

George McGrath's first draft of the Pee-wee's Playhouse theme song lyrics

Paul: I probably wasn't very good at communicating what was in my head to people who are having to translate it and execute it. I have a lot more experience with stuff like that now than I did then.

Phil: Toward the end of the summer, I had this move that I thought was really going to work. I got to the stage and the whole set was there – suddenly you’re in Pee-wee land, a whole crew around, including Rob Zombie, who happened to be a production assistant at the time. I got to the dressing room – and you had to wait until Paul had lunch before you could see him – and the leader of Devo, Mark Mothersbaugh, who was doing the audio, was there as well. He was waiting outside the dressing room, too. He had a cassette boombox to audition the latest mix. He was going through the same thing as me, he was on his tenth remix of the opening music. So I told him I’d set up my VHS deck, give him a cue to go ahead and punch the music, and it’ll be pretty close to being in sync. We got to see Paul, he was in a good mood. I got my video cued up, Mark got his music cued up, we punched our buttons at the same time, and you got that dreamy wail guitar music, the move going through the stuff. Paul said, “Yeah I like it, that’s just what I was going for.” That was the journey.

The aesthetics of American kitsch and Americana pervade not only the titles, but the overall production design of Pee-wee’s Playhouse. Why did those sensibilities have such a strong impact on the look and feel of the show?

Prudence: That sensibility is very much my sensibility. You look at my house and I don’t have one kind of lampshade in my house. Paul’s aesthetics are informed by the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s, so that made its way in there. Gary Panter and Wayne White and Ric Heitzman, I don’t want to say they drew with that in mind, but the entire group was in love with those eras, their promise. The plates and kitchen appliances. It was all fantastical. Nothing straight about it. I think the reason you got hired on that show was that it was your sensibility.

Time lapse video of the shoot for the updated version of the Pee-wee's Playhouse opening in Los Angeles in 1989

Phil: Another thing that people don’t really talk about much is that Paul is originally from Florida, where they have things like snake farms and alligator ranches, these like roadside attractions. I’m from Virginia, and I think Ric and Gary are both from Texas. Wayne’s from Tennessee – home of the schmaltzy Smoky Mountains. In the south you have these bizarre pop art museums and stuff. Civil War battlefields, mini-golf. There’s this giant fireworks stand called South of the Border in South Carolina, and it looks like Pee-wee’s playhouse. It’s just this grotesque thing.

In California you have the giant donut, those stores and stuff like that. There’s a lot of roadside attraction, feeling like a kid in a car, driving by these giant fibreglass dinosaurs for Dino Land, and you want to stop. Pee-wee’s Playhouse is where you can stop at every roadside attraction in the world.

Image Set: American roadside attractions

Paul: One of the movie scripts has an ending like that, a title sequence that's very like that, and the movie, Pee-wee's Big Holiday, has a whole bunch of that stuff in it, and Big Adventure's a road movie that's very inspired by [that]. I was just talking to some people this morning in the editing room about growing up driving in the back of cars on road trips with my family, and looking at billboards going by, and waiting until we got to South of the Border Motel or whatever it was, the next Stookey's or "Pecan Logs in 500 Miles." So, yeah, and the new movie is very Americana, very American. It's not conscious but I do love all that stuff,

The opening also introduces this big, wide world of not just human players, but these more fantastical puppet pals and other friends.

Pterri, Globey, Randy, and Pee-wee in the playhouse

Paul: The one thing we did sort of know ahead of time –while we were making the show – is that we were making something that was very arty and quirky, that there wasn't anything else on TV, in broadcast network television, Saturday morning, anything like it. And that even though it was very informed and homage-y to lots of other kids shows, I think that we just wanted to call attention to all the different medias we were using because we were doing it. Put it right out there so that you see it all.

I like that it's all mixed together and cut together in such a short period of time in the opening because you don't have to wait for something to educate you on “what is it?” To me, once you get through the opening, you know what it is. Whatever's going to start next, you have a whole bunch of stuff you already know, like that you're in a different land, that it's a fantasy, and that there's all these weird things, or unfamiliar things.

You don't know what to expect next but you're comfortable with it at that point.

Paul: Yeah. I always feel like most episodes just start with me doing something, and it seems like after you've just introduced everything. After all that, it seems good to just kind of settle in and see, okay, what specifically is going to be weird right now?

What are some of your personal favorite title sequences, whether classic or contemporary?

Phil: Oh gosh. In terms of contemporary stuff, Game of Thrones is pretty hard to beat. It’s narrative in that way, a wonderfully telling opening story sequence.

Prudence: The opening titles for House of Cards, Catch Me If You Can, Mad Men, of course. True Detective from this year – the song and visuals really work together. Arrested Development, Six Feet Under, The Sopranos, Bosch, The Killing.

Paul: I always loved anything that tells a story. Like The Beverly Hillbillies with “up from the ground came a bubbling crude” or Gilligan’s Island with “a three hour tour”. I’ve written countless shows both in my mind and actual real scripts that open with, if not direct copies of those, then things completely influenced by that where you tell a quick story. I have a least three television scripts that are completely influenced by that.

I love telling a little story like that and I love the corniness. I like that you just need a tiny bit of a reminder of like, “Oh yeah, right. They became millionaires when they struck oil in their backyard, moved to Beverly Hills.” I feel like, why not? Why not get reminded? Why not see all that? And especially if it’s fantastic, I love to watch a show opening. You’re always taking a risk if you do an opening that’s the same every single week. What if people don’t like it?

Those shows you mentioned are so well known partly because of those opening title sequences. People can recite the theme song from memory but probably couldn’t tell you the plots of two different episodes.

Paul: Right. We have like The Munsters and The Addams Family. Snapping and stuff. They don’t even make any cool shows like that anymore. No shows have any cool openings like that. It’s a drag.

The Munsters (1964) season two intro

Cartoon Network’s been doing a bit more creative things with some of their shows, like Adventure Time. It swoops in through the entire world and then gives you this little guitar jam.

Paul: Hmm. Yeah, I know the opening to Adventure Time. You’re right. I just love like dizzy, jam-packed openings. Something like The Jetsons and The Flintstones.

I love changing it up. Roseanne used to do it, didn’t she have like a little different ending to her show’s opening title sequence sometimes? Almost the way Matt Groening has the Simpsons couch gags.

Adventure Time (2010) title sequence

What can you tell us about Pee-wee’s Big Holiday? Wonder Showzen’s John Lee is yet another pretty interesting person to collaborate with.

Paul: Oh, my god! I guess what I'm trying to say is I've collaborated with just one amazing person after the next. And even though there was a lot of frustration the first year of making Pee-wee's Playhouse because practically no one had done their job before – it was everyone's first job, so there was a lot of inexperience, and that made for things being way more time consuming. It was just very hard. The conditions were very, very difficult.

It was just like when you live in Los Angeles and you go anywhere, every single person around you is an aspiring actor, like the waiter, the valet, everybody. When you go, “Are you an actor?” to somebody on the street, it's like a joke, almost. You would always assume the answer's yes. And it's sort of like that on my stuff, where I turn around and even the craft service person or the person pushing a broom, everybody is an artist. Everybody's somebody really interesting and unique and creative, and I do my best and so do other people, like department heads to really nurture it, to make sure we develop it as much as possible. In other words, to make sure that people realize we not only are comfortable hearing suggestions, we welcome if you have an idea.

Prudence, Phil – looking back on Pee-wee’s Playhouse, how would you describe the overall experience?

Prudence: It was like being paid to eat ice cream. No, I’m serious! I never thought twice, and I never wanted to leave before 10pm.

Phil: You had Paul and Phil Hartman, Miss Yvonne (Lynne Marie Stewart), Cowboy Curtis (Laurence Fishburne), all these different folks.

Members of the Pee-wee's Playhouse title sequence production crew

Prudence: Your friends were there, you were all doing something you really liked. It was like finally you weren’t just making hamburgers for McDonald’s. It wasn’t a product at all, this was playtime, this was real. It was a phenomenal time.

Phil: I will confess, having worked on it so intensely, and my wife as well, when we got up to watch the first show, I was kind of disappointed. I thought it was so raw and so challenging and so different from everything else on TV that it probably wasn’t going to make it. I thought we had done all this work for nothing. I was completely wrong. I’m happy to be wrong in that way any time.

Paul, it must be really exciting to have this revival of Pee-wee that’s been getting such a great response. Are you happy to be getting back to the character?

Paul: I can't even believe it. I've heard lots of people say that, and I don't want to appear jaded in any way [laughs] but when people say that I immediately think what's anyone going to say to me besides “I'm a really big fan”? Like, people don't really take the time to come up to you to go like, “Hey, hi, sorry, so sorry to interrupt you. I just wanted to let you know, not a fan,” or “I really hate everything you do,” or “Your voice always irritated the hell out of me, I'm like so not a fan of yours.”

So I don't know, I just don't trust it. Like I hope I can believe you, I don't think anyone is lying to me when they give me a compliment, but I just never believe it. Friends of mine are going like, oh no, lots of people can't wait for your movie. I just can't picture it.

[Laughs] Have faith. Your fans are out here.

Paul: Well, I'm super excited because we're weeks away from locking the picture, and the score is being recorded at Abbey Road Studios by the London Philharmonic. It’s booked and the score isn't quite written yet. But, oh my god, we're listening to bits and pieces of what will become the score and we're tightening the picture every day to where four or five weeks from now it's locked. And then I'm gonna see it with 150 people at a top secret screening. It's so exciting – I can't even believe it. You're talking to me really at the height of excitement about it because it's a total secret. No one has seen it, and practically no one even knows what it's about.

Pee-wee's Big Holiday co-writer Paul Rust, star Paul Reubens, and director John Lee

Even just knowing that more Pee-wee is coming makes people overjoyed. What do you enjoy most about returning to Pee-wee?

Paul: Boy, I'm just gonna make this 100 per cent corny...

The situation calls for it, go ahead.

Paul: The artiness of it. You know, the art! The part where I'm surrounded with like, really cool arty people who view everything – who filter everything through an aspiration of making something seriously beautiful. It makes me cheer up even just telling that to you, you know?

Seriously, I love being able to do this kind of stuff. I want say it's as fun as it looks – and this is probably gonna ruin what I just said – but a lot of people say to me, “Oh, that looks like so much fun.” Well, it super is fun! And it’s also way more work than most people think. But yeah, it's the most fun kind of job even though it may be billions of hours. All those insane schedules and stuff. When you're doing it with a group of collaborators, like everyone's real happy and thankful, you know? Including me. We all know we have killer jobs, and we're like lucky that we're the people we are and have the aspirations we do, and here we are fulfilling them! That's our job, you know? I'm going to work, but look where I'm going and look what I'm doing!

Exactly. That’s the most amazing thing. Maybe we could just end on that note. Thank you very, very much for your time.

Paul: I've got a lot more stuff I wanted to talk about really slowly right now.

Oh, okay, go ahead.

Paul: I'm just kidding you! [Laughs]

Supplementary: Pee-wee’s Playhouse season two (1987) opening

Supplementary: Pee-wee's Playhouse Christmas Special (1988) Opening

For more info and behind-the-scenes video about the making of Pee-wee's Playhouse be sure to check out Pee-wee's Playhouse: The Complete Series box set.

LIKE THIS FEATURE?