Director Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby was at the epicentre of cultural upheaval when it premiered in June 1968. Based on Ira Levin’s novel of the same name, which was a smash hit in the literary world, Rosemary’s Baby captured the zeitgeist of the youth movement and the internalized fears of a new generation disenfranchised by the death of the American Dream. The film industry in the 1960s was waning. Once guaranteed successes were succeeding with audiences less and less. The youth, who were rejecting mainstream culture, wouldn’t pay to see films that reaffirmed the cultural norms they were rebelling against. Hollywood had to learn to play ball with this social change lest it be left in the dust.

The mid-1960s to early 1980s in America saw the advent of the New Hollywood film movement, or American New Wave as it is also known. The studio ethos of tightly controlling every production was gradually replaced in favour of handing over control to the director, mirroring French and Italian New Wave cinema. By giving directors authorial control, Hollywood films steadily shifted away from the carefully crafted, didactically happy American fetishism which had preceded this era and moved towards themes of concern, anxiety, and even fear over where the country and the current generation was heading. The post-war euphoria had worn off and the world’s greatest superpower was awakening from a too-long party, hungover. The optimism of the white picket fence had faded, the young promising president John F. Kennedy had been assassinated, the civil rights movement was ongoing and shedding light on the internalized racism within the country, and the realities of the Vietnam War were infiltrating the nation’s psyche. In the midst of all of this, a relatively small story about a newlywed couple would captivate the country.

Rosemary's Baby (1968) original trailer

It seemed as though Rosemary and Guy Woodhouse’s dreams of success and social status were becoming reality when they found a too-good-to-be-true apartment in The Bramford in Manhattan – the Bramford being a cinematic stand-in for the real-life Dakota apartments just off New York’s Central Park. Guy and Rosemary move into their new home and soon encounter Minnie and Roman Cassavetes, the elderly but forcefully social couple next door. Rosemary asks Guy to try for a baby and after a night of socializing with the Cassavetes; Guy relents and agrees to try. On the night they plan to attempt to conceive, Minnie drops off a mysterious dessert which Rosemary is initially wary of but consumes at Guy’s behest. Rosemary soon passes out and her dreams bleed into reality as she realizes that she is, in fact, not dreaming but being raped by a monstrous force.

Rosemary learns she is pregnant shortly thereafter and grows fearful of her neighbors and Guy, whose career as an actor has miraculously taken off ever since he gave Rosemary Minnie’s dessert. Rosemary soon becomes convinced they are part of a coven who want to sacrifice her unborn child. The true terror unfolds when Rosemary gives birth while trying to escape her husband and doctor. She learns that she has given birth to the Antichrist and the coven summoned the Devil to rape her nine months prior. Rosemary’s Baby ends on an ambiguous note as Rosemary does not retreat from the child but rather looks on, almost lovingly and considers her future.

Mia Farrow, producer Robert Evans, and director Roman Polanski on the set of Rosemary's Baby (1968).

The tension of Rosemary’s Baby lies in the competing expectations of Rosemary and the coven. They both want a child, but for very different reasons. The film’s femininity cannot be understated, as Rosemary Woodhouse represents everything a good young wife of the 1960s should be. She’s educated and polite, but she is also demure and defers to Guy often. She keeps her home well, decorating and cleaning it, and wants what society has affirmed is the greatest achievement for any woman of that era: a healthy child. The coven also need a healthy child but this one needs to be only partially human. They seek to bring the Antichrist into the world and start anew, with Roman saying at the end of the film “the year is One!” It is these competing but linked objectives that are presented from the opening moments of the film in Rosemary’s Baby’s classically formed title sequence.

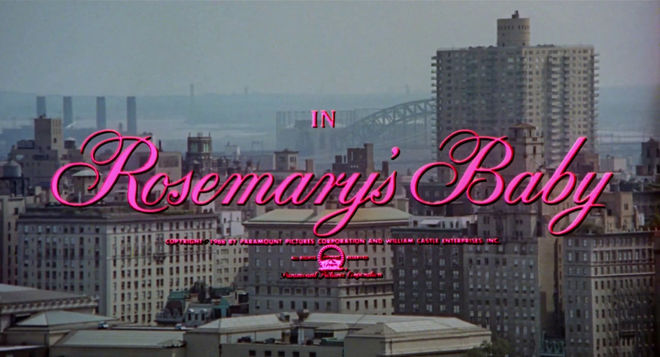

As the faded Paramount Pictures logo graces the screen it is accompanied by several eerie and tension-filled musical notes, creating immediate suspicion that something is amiss. As the logo dissolves, the New York City horizon appears and the first credit text appears in a curly, feminine script, splashing a vibrant pastel pink across the dingy beige skyline of the modern city. The camera steadily pans across the city with few visible or truly noticeable landmarks in sight. The panning move seems almost unsure as more credits in the same pink script continue to dominate the screen. The camera soon comes to rest on an ominously gothic building in the middle of the city as the screen is dominated by the aggressive architecture of its peaked roof with multiple angles and edges dominating the screen, cutting through the pleasurable and comfortingly familiar typography on the screen. The darkened roof of what we will soon learn is The Bramford already feels unsettling and the guided camera movements which at first seem innocuous are now ominous.

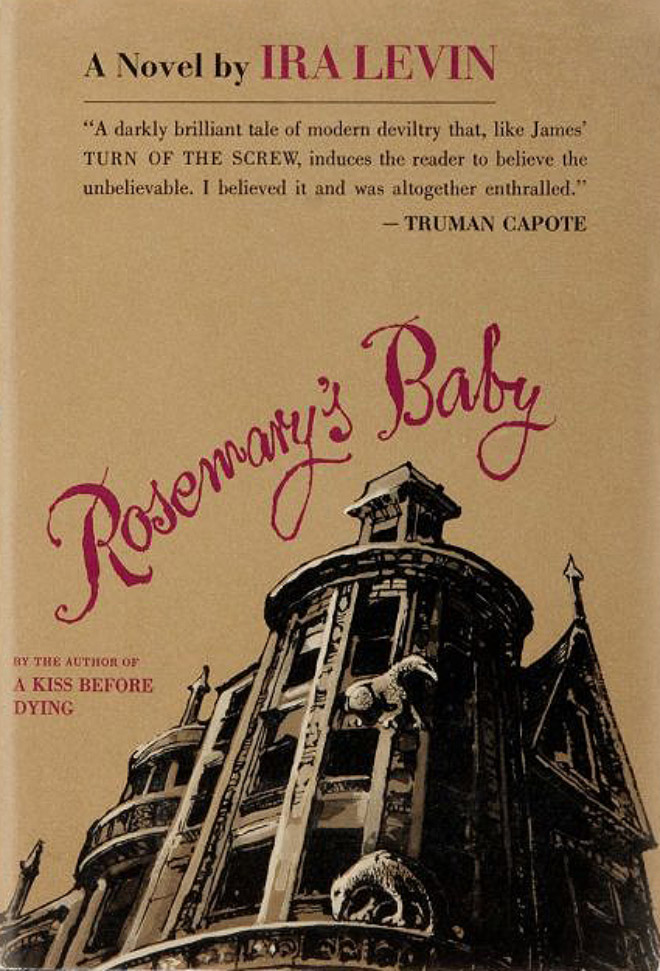

The style of typography used in the opening of Rosemary’s Baby is pulled directly from the first edition of the book, which also featured tightly curled lettering set against an ominous building.

Rosemary's Baby (1967) book cover, designed by Kenneth Miyamoto

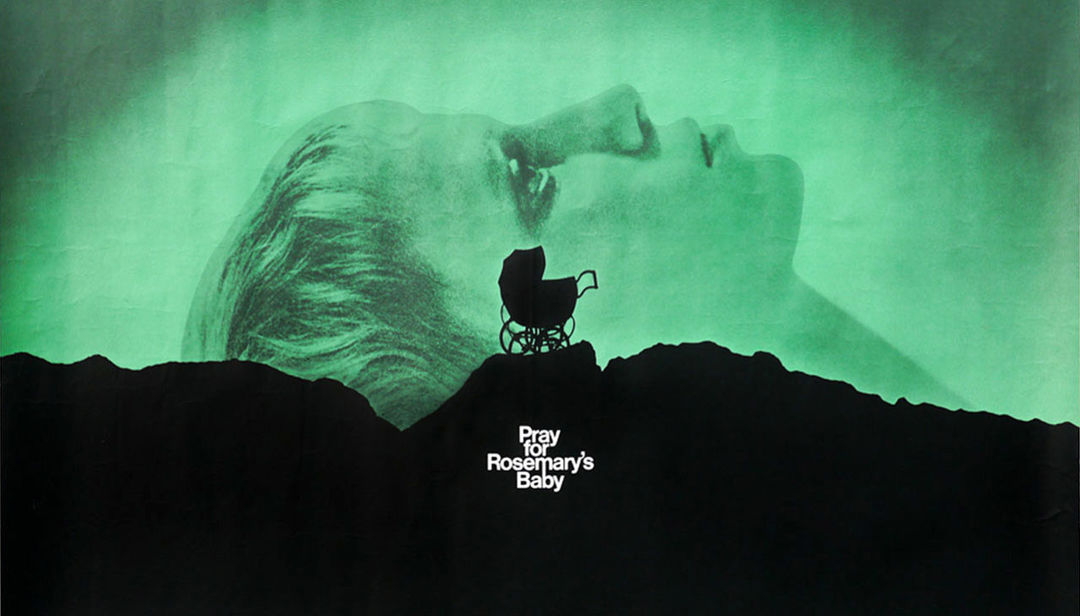

Production of the film’s title sequence was overseen by Stephen Frankfurt, who also helped create the highly successful “Pray for Rosemary’s Baby” marketing campaign which incensed the public and created debate before the film was released.

Rosemary's Baby (1968) quad poster art featuring the "Pray for Rosemary's Baby" tagline.

Title designer Wayne Fitzgerald, who executed the sequence, adapted the design elements of the book’s striking cover and elaborated on them. The title sequence pulled from Polanski’s own tendency to lift passages directly from Levin’s book by transposing the cover art to the screen.

Rosemary's Baby (1968) title card

Throughout the opening title sequence, a woman’s voice (Mia Farrow) sings a strange tune interspersed with sharp, jarring notes – the la-las of the wordless lullaby negating the ambient noise of the city streets. The voice in the song and the script on the screen are aligned. They represent womanhood, femininity, sugar and spice and everything nice. These are the elements that seem familiar, expected and are pleasant for the audience to engage with. The other elements, such as the slowly moving camera and the protruding direct notes present within the music, hint at something else, something more sinister, more calculating and evil. The camera’s pans imply a force watching or looking for someone or something and as the credits and music climax it becomes clear that that the gaze seems to have been awoken by the young couple about to enter The Bramford. Our gaze as viewers is directed towards the building, inferring a malevolent presence already at work and tied to the physical location. At first the movement of the camera seems almost innocuous but as it focuses on the Victorian building, a sinister feeling envelops the camera’s frame. The curling script and feminine voice prepare us for Rosemary, a young woman who believes she can have it all because she has obtained everything society has told her to acquire. Her desire to live in The Bramford stems from its prestige. The pink font and the dreamy la-las signal her girlish nature, the feminine wants and desires that lead her down an unknowably dark path.

The Dakota building as it looks today. The apartment doubled for The Bramford in Rosemary's Baby (1968).

The camera's gaze initially seems unrefined and unfocused, but in a long single shot, it lands on the site of horror for the film: the Bramford apartment complex. Its gaze, as the final credit appears, settles on the young couple seeing the desirable apartment that ultimately leads to their doom. The camera can reflect the predatory nature of the coven within the Bramford, the evil spirits that seemingly lie dormant within the building's walls coming to life, or even the Devil himself, becoming acquainted with the young couple.

The other elements of the title sequence, most notably the typography and formality of the credits themselves set against Farrow's singing, set up the other main theme of the film: female desire and expectations. While Rosemary is determined to start a family, it is ultimately her pregnancy, which comes at the hands of the coven, that creates conflict and confusion within her. Her desire for the expected female experience of being a wife and a mother is no less real or valid than the coven's desire to see the birth of the Antichrist. It is the normal expectations on a young woman that allow the coven to control and coerce Rosemary for as long as they do.

The coven surrounds Rosemary (Mia Farrow) on the set of Rosemary's Baby (1968)

The title sequence of Rosemary's Baby pits the two strongest desires within the film (both which end in the birth of a child) against each other by giving them equal filmic importance, weight, and screen time. With the opening moments of the film, the role of femininity, motherhood, and manipulation are all set against each other with their different motives, playing with each other through unsettling music, camera movements, and a final shot of a young, happy couple who have no idea what is about to befall them.

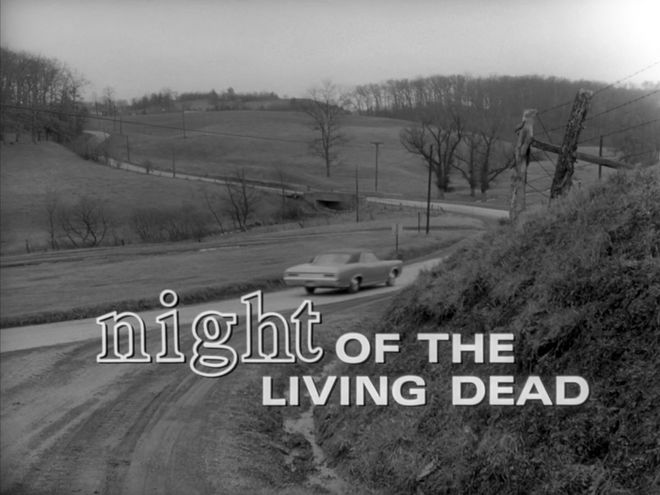

The other seminal horror movie released in 1968 was George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead, which also employs an unexplained viewpoint in the opening credits. Romero’s camera is stationary and in the first shot of the film, it remains still for an almost unnerving amount of time as a car drives along a road towards the camera and passes it by. A similar shot is repeated several times over, implying that someone or something is watching this car and its passengers, creating an unease between the audience and the camera’s gaze.

Night of the Living Dead (1968) main titles, designed by The Animators

Stanley Kubrick repeated this trope with the opening credits of The Shining. As the Torrance family drives towards the haunted Overlook Hotel, the camera swoops in and follows them from above as they drive, once again implying an unseen force is already at play.

The Shining (1980) main titles

The power of this trope is that it never truly names or depicts the evil or malevolent force in question. Yes, there are sinister forces at work in these stories, yet they are rarely the only ones at fault as they heighten and play with traits already existing within the characters. Part of the New Hollywood ethos was to move away for the didactic nature of filmmaking in generations past and force audiences to grapple with the realities of moral ambiguity. As the politics of the 1960s and 1970s became more convoluted in the eyes of the public, the black and white notions of good and evil were becoming increasingly irrelevant. What these openings set up so clearly is that something is already happening before the first lines of dialogue have been spoken, something that has been waiting for a very long time and now has the perfect vehicle for its plan. The audience will never know what these forces are or what truly caused them to awaken, only that it can happen at random. Within the horror films of New Hollywood, horror was no longer situated in faraway European castles, it was all around you, waiting for the right moment to strike.

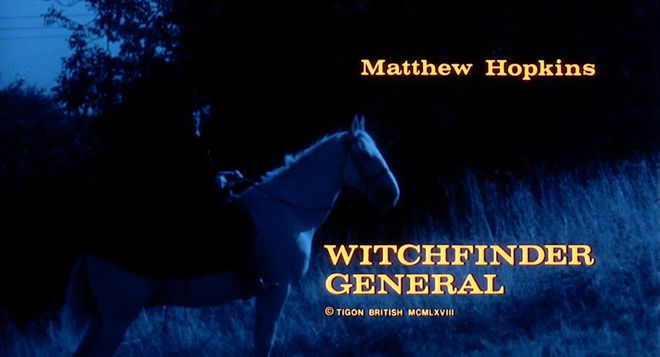

Other horror films of the 1960s still relied on old tricks and tropes to thrill and chill their audiences. While there were some notable exceptions with prestige offerings like Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho and Robert Wise’s The Haunting, horror of that period was still indebted to familiar gimmicks from equally familiar faces such as Vincent Price. The title sequences of many of these films were static title cards, moments that saw the screen freeze while the actor’s name, usually Vincent Price’s, stood above the title, then the film would continue. Within these films, the title sequences were a function to highlight the familiar face that the audience was about to go on a ride with. The opening of The Witchfinder General begins with a harrowing hanging of an accused witch then freezes for a brief title card which morphs into more credits and then barrels on with the rest of the story.

Witchfinder General (1968) aka The Conqueror Worm main titles

The title of sequence of Rosemary’s Baby, as well as the other films mentioned, plays with the gaze of the camera, implying there is no true authorial control over the events that are about to be seen and that everything is suspect.

While title sequences have evolved a great deal since 1968, Rosemary’s Baby has remained a stand out of unsettling subtlety. The brightness and style of the typography and music choices separate it from its background, while the viewer is forced to reconcile the two elements presented to them on-screen as both comforting and unnerving. Alex Ross Perry’s Queen of Earth employed a similar style for its end titles, inherently referencing Rosemary’s Baby in the process. By showcasing Elisabeth Moss’ Catherine’s tear stained face close up, the almost tormentingly cheery pink, curly script splashed across her face implies a juxtaposition between what is shown on the surface and what is bubbling underneath.

Queen of Earth (2015) title card, designed by Teddy Blanks

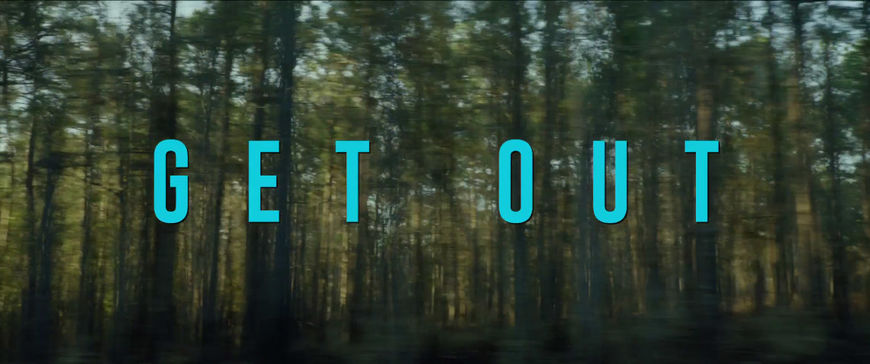

Jordan Peele’s 2017 film Get Out employs a similar theme with turquoise text and Michael Abels’ main title theme “Sikiliza Kwa Wahenga” set against the unfamiliar backdrop, transforming the title card into a warning coded to the tell audience that something is amiss.

Get Out (2017) title card, designed by Filmograph

Producer Robert Evans, the Paramount executive behind Rosemary’s Baby, has often said, “There are three sides to every story: Your side, my side, and the truth. And no one is lying.” Memories shared serve each differently. Rosemary’s Baby stays firmly in Rosemary Woodhouse’s gaze, the audience is aligned with this likeable young woman with simple wants and needs, but the ordinariness of her story is clouded by the eerie quality of the opening title sequence, one which underneath the feminine elements seems to emit a low-level rumble of evil, almost undetectable yet screaming volumes.

Director of Photography: William A. Fraker (as William Fraker)

Title Designers: Stephen Frankfurt, Wayne Fitzgerald

Music: Krzysztof Komeda (as Christopher Komeda)