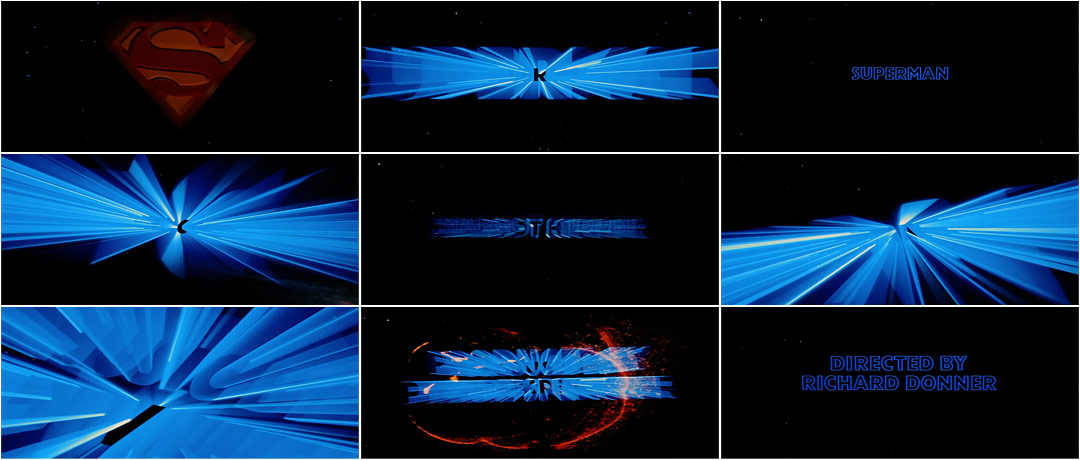

Beginning with Stop, a short film Richard Greenberg made in university in the late ’60s, the thread that would run most clearly throughout much of the title design of R/Greenberg Associates is a particular application of typography. Their first major film project, the teaser and opening title sequence for 1978's Superman, gave them a start in the industry. Now, the sequence is an iconic piece of design for film, but back in the late '70s, a fair amount of ingenuity was required to develop the technology to allow the title to "swoop" through space.

The Greenbergs would go on to design the titles to films including Alien, Altered States, The Dead Zone, The Untouchables, and many others, eventually turning their two-man title design operation into a full-service international agency responsible for some of the most iconic commercial and film work of the last 35 years. But first, there was Superman, in all its pre-digital glory.

Title Designer RICHARD GREENBERG and current R/GA CEO ROBERT GREENBERG speak about their work on Superman in this excerpt from our feature article R/Greenberg Associates: A Film Title Retrospective.

So, how did you progress to handling bigger movie titles?

Robert: We got a call from Steve Frankfurt who was president of Young & Rubicam Advertising at the time. He opened a division in feature promotion and gave us the opportunity to work on Superman.

Had you known each other previously?

Robert: No, he had heard of us and called for our reel, but he didn’t know us.

Richard: With him, we worked up an idea for a graphic trailer which is very similar to what became the titles. Dick [Richard] Donner, the director of the movie, was a contemporary of Steve’s, and became a very successful movie director. His first big movie was The Omen, which is pretty incredible, and then he got Superman. They brought me over to London and we talked. R/GA presented the idea of these streaking titles to Warner Bros. and I told them I knew how to do it.

And did you?

Richard: No, we had no idea how to do it! For about two weeks we kept trying to figure it out. Then we realized we had to let the Oxberry run and put a black card in front of it to end the streak. The streak was created by putting a negative and positive Kodalith together with a blue gel in between. The blue gel allowed enough light through to create that streak.

Superman teaser trailer, designed by R/Greenberg Assoicates

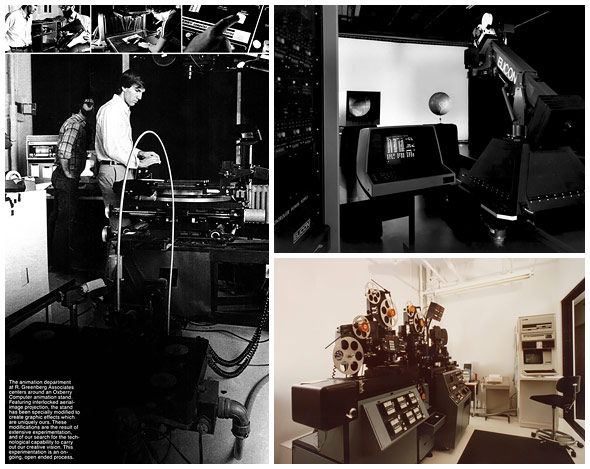

Superman was the first comic book movie with [Grade] A actors in it like Marlon Brando. So the idea was to announce their participation in a fabulous way. We thought it would cheapen the tease if any real footage was shown. So that’s what we did, and it was developed for the advertising materials and then refined for the title. Dick was working with a high-end London optical house at the time and if they had been able to do the streaking they would’ve gotten the job. But they didn’t really want to come to New York or fly me back there, so it worked out because nobody but us could do it! Then we bought an Elicon early in the ’80s. It was a very crude version of a motion control system.

How did that work?

Richard: Hah, it didn’t quite work. It sort of worked. Those titles were created by re-working the idea of what the animation stand was; you would literally move the camera on the rostrum stand and cap it at particular points to create a kind of three-dimensional motion. Everything we did until the mid-’80s was pre-computer — Superman is all pre-digital. It is more beautiful, in a way, than digital work could have been. There will be a point in the near future when — and we’re almost there now — films won’t be shot on film anymore. We came in as everything was only beginning to change over throughout the industry.

It seems like for many of your projects — like Superman with that streaking effect — you came up with the idea but didn’t know how to execute it. You had to invent a way to produce the effect.

Various equipment systems implemented at R/Greenberg Assoicates

Robert: That was part of our creative process. We would sell ideas to clients based on 35mm film frames. We’d make storyboards that were created on the animation camera, printed out as a half transparency, and put into frames, and then we’d bring a light box with us and show the client the progression — as frames. And so for the Superman titles, when Steve Frankfurt said, “We’ve got to go ahead and make this thing,” we were clueless about how to do it. We had to invent what they called “slit-scan.” Later, we found that Bob Abel, as a competitor, had really invented slit-scan before us for 2001: A Space Odyssey. But we didn’t know that! We had to figure it out.

To describe it in more technical terms, the way it happened was that there was a motorized capping shutter on the camera. That allowed us to leave the lens open to do the storyboard still frames for the teaser, and then we had to buy equipment and design it to be able to do motion. We had to do it later in CinemaScope for the opening titles, which are anamorphic. That was really, really difficult because it had never been done.

Then, when the titles were inserted, they had an outline, which was a problem. The whole thing became a nightmare optical shoot that took something like 14 to 16 hours. Every time we’d do it, there’d be something screwed up, and it got down to the wire. Stuart Baird, who was the editor, was there and we only had one more shot at it. Harvey stayed up all night, we all did, and it came out the next morning with a hitch in it, but nobody saw it. We covered it over with a music cue! And then it made it, you know? Stewie took the Concord and got it there just in time. Our career was made on something that made it just by a hair. I think a lot of things work that way.

Then we went to the opening. Richard Donner had congratulated us before we got there, so they had seen an earlier version. Seeing it put together with the movie and not to mention the great music — it was pretty awesome.

So the Superman titles got a great response and gave you a confidence boost?

Richard: People loved it! I had never been at a screening before and we were at the Ziegfeld in New York City, which is a giant theater, with all of the high rollers in New York, and people applauded after the title sequence! I’ve never seen that happen. And Dick Donner was there and so was John Williams, who had done the score. It was a really big thing. I’m very shy, but never after that did I have to explain who I was.

Since the teaser trailer for Superman won the Clio that year, it gave us something that’s very, very important in New York advertising: a tie to the entertainment business, which — I don’t care what New Yorkers say — is very fascinating to them. Everybody in New York wants to be a movie director. When they say they don’t, that’s bullshit.

LIKE THIS ARTICLE?