Part comic book, part actioner, part kangaroo, with a bra made of missiles and a dash of kitschy musical, Tank Girl is a film unlike any other. Rachel Talalay’s 1995 adaptation of Alan Martin and Jamie Hewlett’s anarchistic comic of the same name is a no-holds-barred romp through a post-apocalyptic wasteland.

It’s a film for fans of bonkers, ostentatious, rule-breaking cinema. It’s also for anyone excited by the words “Rippers designed for the screen by Stan Winston” or the fact that Iggy Pop makes an appearance as a pedophile named Rat Face. Lori Petty’s Rebecca Buck (aka Tank Girl) is an obnoxious, ultra-violent outlaw, riding a water buffalo and speeding tanks through the desert, hell-bent on destroying the evil Water and Power megacorporation. She is larger than life, a woman on the edge, poking around gender stereotypes and fascist ideologies with glee. She will never break.

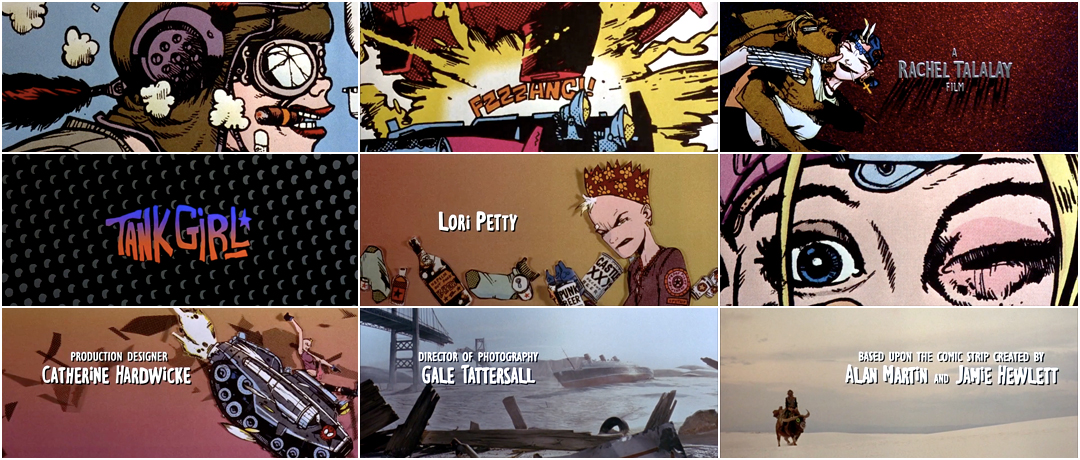

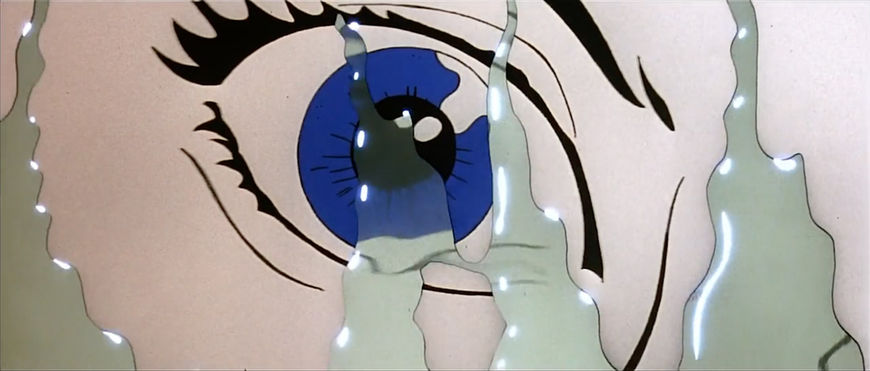

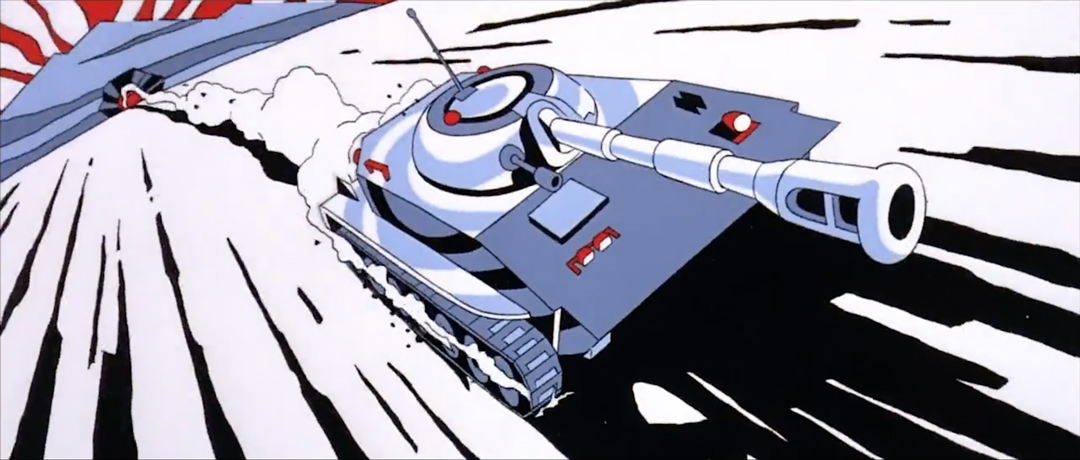

Tank Girl grounds itself in the world of its source material, with wild splashes of artwork and several animated sequences drawn by Hewlett and produced by Mike Smith and Colossal Pictures. This artwork carries the film both in terms of its narrative trajectory and its tone, providing bookends for the picture as well as much of its heart. The opening title sequence, created by designer Andrew Doucette and featuring a new recording of Devo’s energetic “Girl U Want”, is a slam of colour, heavy metal machinery, and cocky smiles that perfectly amps audiences for the mad ride to come.

Though the film was a box office bust, it did much to catapult its titular character into the American mainstream. The influence of Tank Girl can still be felt to this day, having made an indelible mark on music, fashion, and anyone punk at heart.

A discussion with Director RACHEL TALALAY and Title Designer ANDREW DOUCETTE.

How did you first encounter Tank Girl? How did this project come to you?

Rachel: I was given the comic book by my step-daughter for Christmas. And I spent a year pursuing it, trying to get the option for it, which I finally did, and then I developed it from scratch. I pitched it and developed it and put the script together so it was very much my project.

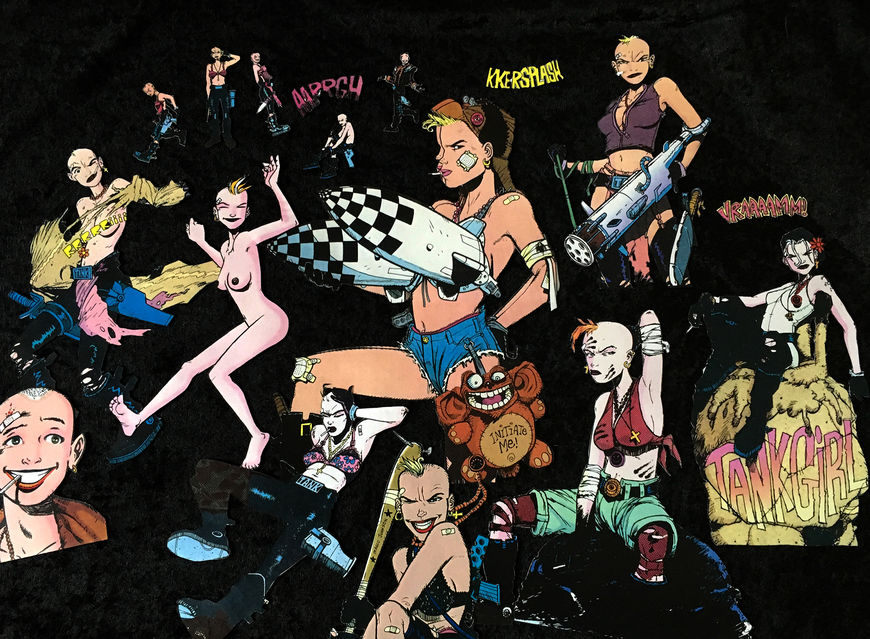

Andrew: I think my friend Nels Israelson, the photographer, said, “Have you ever heard of Tank Girl?” I said no, and he said, “You should check it out, I’m working on this film!” He’s the one who had the comic books and was able to give them to me, and I cut them up. But I hadn’t heard of it before.

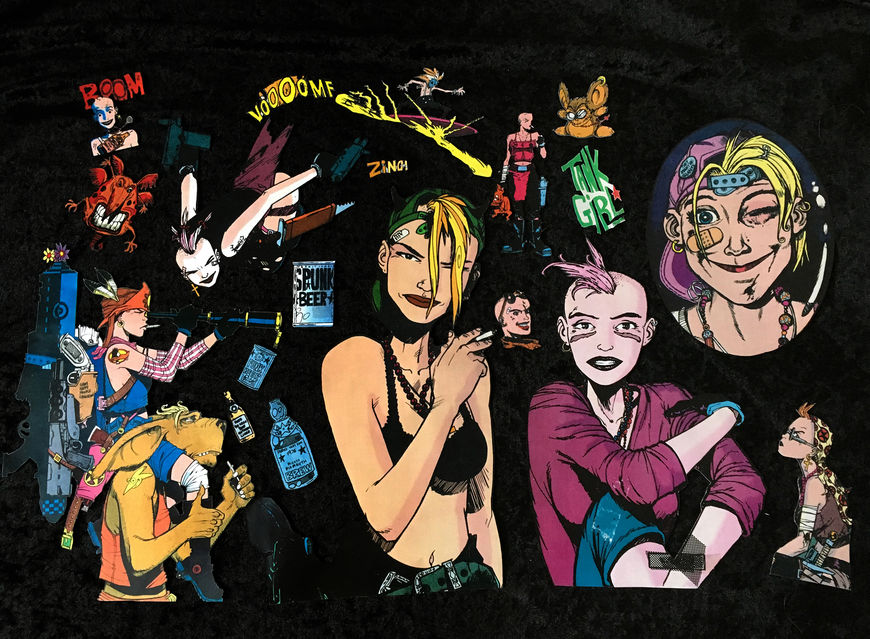

Tank Girl artwork by Jamie Hewlett and extracted by Andrew Doucette for use in the title sequence

When you read the comic and first encountered Tank Girl, what was your reaction?

Andrew: I thought it was great! It had a real cool sensibility. I mean, Jamie Hewlett, he’s got such a style.

Rachel: It’s such an iconic image. I think all strong women react in the same way to this outspoken crazed female icon. I was such a punk warrior. When I went in to pitch it – I mean, all you had to do was show the image. And when we sent the script out, the cover page was a comic book page. Even now when I talk to people who design for video games they say that there’s never a pitch for a female character that doesn’t include an image from Tank Girl.

She’s the tough, punk warrior woman. She’s the icon of that. And every tough, interesting woman I know wants to be her.

So how did you go about setting up this character? How did you envision the opening titles of the movie?

Rachel: I said, well, we need to use images from the comic book! I worked very closely with [Tank Girl production designer] Catherine Hardwicke. I can imagine her saying, I know a guy who will do a great job.

Andrew, you had been doing mostly music videos around this time, right?

Andrew: Yes! I’d done like three or four feature titles and a couple of TV titles before that, but the way the whole thing got kicked off was with Nels and Catherine, who was the production designer. Catherine suggested I put a reel together and send it to Rachel. I was hired to do the title sequence and I had a set fee for that. I was hired basically because I was known to be able to shoot quickly on an Oxberry animation stand and I could get through a lot of footage.

Rachel: I wanted to make it very clear what you were getting into. I wanted to do as much as I could to advertise Jamie’s art and what we were trying to do with that title sequence. I think because you’re coming into this post-apocalyptic world, I wanted to make sure that you completely had fun before that. Hence using “Girl U Want”, that Devo song but re-recorded with a punk female voice. I wanted you to feel the characters, I wanted you to feel the style – Jamie’s style.

I didn’t make Tank Girl for people who are literal. This is for the post-punk warrior feminists.

Various tanks and typography drawn by Jamie Hewlett and extracted from Tank Girl

Rachel: Jamie was hired to do designs for the film and I have boxes of designs that Jamie came up with for the bedroom, for props. He designed the tank and then we had a practical designer who took Jamie’s crazy ideas and turned them into something that we could actually make.

I always said, I want to make a film that’s either a 10 or a 1 so that if it averages out to 5 it’s okay. But I don’t want to make a film that’s a 5. You either love it or you hate it. People who hate it, just hate it. If you think that it’s weird she has different hairdos in this future with no water, then you’re never gonna get this film! I didn’t make Tank Girl for people who are literal. This is for the post-punk warrior feminists.

You mentioned the Devo song, “Girl U Want.” How did that come about, how did you choose that song to start off the film?

Rachel: I’m a big fan of punk music. We had a lot of input from lots of people about the music, but that was one of the songs that I loved and wanted re-recorded with a female voice.

Devo – "Girl U Want" music video, 1980

Why was it important to have it re-recorded with a female vocalist?

Rachel: I wanted to switch it up. I didn’t want it to be the standard Devo song, because the Devo song felt like – because of their mechanical nature, the mechanical nature of Devo, it didn’t have the edge that I wanted it to have. I remember fighting with the producers about it, actually, because they said, “Her voice is screechy!” And I said, “No. Her voice is cool.”

Actually, as we talk about it, I remember having to go to the executives and having to let them make the decision about which version of the song we were going to use. There was a male executive who said, “Agh, it’s so screechy!” Hello? That’s what punk music is!

There’s “Let’s Do It” too, which was my idea. The song, and the dance number. Out of the blue, we just wrote new lyrics for it, including my assistant, who wrote a series of lyrics for it. She said, “I can’t believe I just wrote new Cole Porter lyrics and we just put them in this movie!” [laughs] Without anybody’s permission!

Scene from Tank Girl featuring a version of Cole Porter's song "Let's Do It, Let's Fall in Love"

How did you approach using animation in the film?

Rachel: Well, there’s three things, really. There’s the title sequence, which are the graphics from the comics. There’s the still panels, which Jamie designed and drew. And then there are the actual animation sequences which were done completely separately.

Let’s start with the title sequence. Andrew, what was your process?

Andrew: I worked with an editor named Ivan Ladizinsky who actually went on to become an editor for the Survivor TV show. He and I worked on one of the earliest non-linear editing systems called D/Vision. This is back in ’95, so we would sit there and do an offline edit together.

Rachel would pop in to approve or disapprove. At the end we gave her two versions of the montage that we cut together and she made the decision about which one she wanted.

Rachel: They came back with such brilliant stuff, and I thought, “This is working great.” I remember thinking, “God, this is so much better than what I asked for.” [laughs]

Andrew: We had two versions which were very similar, and it was all cut to the Devo song with the female vocal on it, which was a good choice, I thought.

What did you shoot with?

An Oxberry animation stand is a type of rostrum animation camera stand used in photoanimation.

Andrew: It was all shot on 35mm, on two different types of animation cameras. The first is the one that I was most familiar with and I could use in my sleep, it was an Oxberry. They sometimes call them downshooters. It has, you know, a plane bed that you can rotate and it has pegbars so you can rotate the handles and make east-west-north-south moves on. And then the camera can go up and down this long column to shoot the footage. Except for the camera going up and down everything was hand-driven by handles and spinning the beds.

Credit composite featuring multiple mattes and the final frame from the title sequence

Andrew: At Lumeni, where I work now, they had two mechanical concepts, animation cameras. They were computer-driven, and you could do anything on these cameras. For the main title, we ended up bipacking inside the magazine that holds the film you’re exposing, a hold-out matte that we had shot previously, and it would hold out the footage.

Bipacking is a technique used in cinematography and animation of loading two reels of film into a camera so that they both pass through the camera gate at once.

Like, if we were shooting the sandpaper background – I actually bought sandpaper at the hardware store – put that down on the animation bed, we would bipack the film with hold-out mattes for the titles with their drop shadows, which were actually slit-scans. The drop shadows – the shadows coming off the type – were old-fashioned slit-scan, like in 2001: A Space Odyssey, that kind of thing. Those were then bipacked, so you could shoot that, shoot the background sandpaper, and then you would roll the film back again, take the hold-out matte out and then you would expose the face of the letters, the white. And all of this was being wiped on and wiped off with a pan cel that I spraypainted black with spatter-paint. A kind of spatter-paint pan cel, so it would go zhhhh! across the back – the bottom lip footage – of the litho negs and then that would give you a transition off and on. It was quite complicated, but it was fun!

Your memory is so clear!

Andrew: [laughs] I have journals going back to the ’70s and I can go back to any day. It’s kind of silly, but it comes in handy sometimes.

Image Set: Photographs of Andrew Doucette's journal during the production of Tank Girl, beginning on January 4, 1995 and ending on February 24, 1995

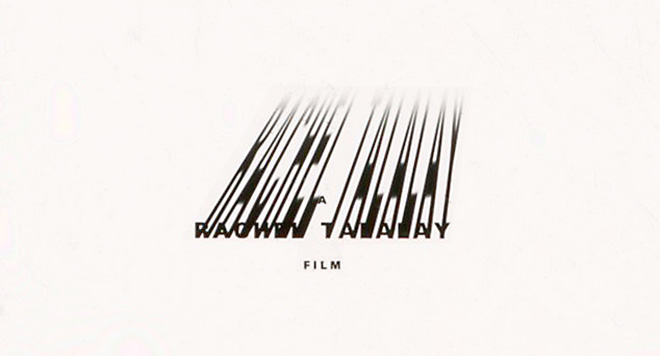

Andrew: Actually, I really wanted to talk a little about those shadows. The first three cards, which are called the “intro” cards – the “MGM Presents” and the “A Rachel Talalay Film” – they have these long black-and-white shadows. You can see a light source off screen, moving, across the sandpaper.

The "A Rachel Talalay Film" intro card as it appears in the title sequence

Andrew: It looks like it’s an actual cast shadow, but in fact the shadows were caught with a slit-scan effect. Basically the camera’s going up and down in one long exposure, and back up again, and another long exposure up and down, which then traces on the film. We had to rig a light source off of the rotating bed, and then it had to swivel slowly around for the course of those cards and look like it’s is actually shifting, like headlights or something. That was pretty cool.

Initial "A Rachel Talalay Film" credit shadow test

How did you work with the typography?

Andrew: I worked with Marilyn Frandsen who was working on the typeface and prepared all the cards for me. I didn’t design the typeface. The actual “Tank Girl” typeface is different than the cards, but it was her baby. She was the one who was in charge of the typography.

For the animation sequences in the film, those were animated by Mike Smith, right?

Rachel: Yes, he did it. I saw his work and it was phenomenal.

The reason I put animation in the film was because we couldn’t afford to do the action sequences. We couldn’t afford the tank. It wouldn’t even run, let alone run backwards or with any kind of speed!

Jet Girl and Tank Girl on the tank

We didn’t have a jet – the flyer was just on wires – and the miniatures weren’t working particularly well. We needed a way to get the action sequences. So I said, well, the only way we’re going to have action sequences that really feel like the comic is if we animate them. That’s where the animation came from.

Andrew: They hired Jamie to come up with new drawings that would explain things happening in the film, and asked me, “Can you shoot those for us, too?” I would do all these panel moves and – they came in as a big stack of 8” x 10” colour transparencies – and then I would strip those up and get ‘em ready for the animation stand. I would do moves on those, and some of those were used in the title sequence, and some of them were used throughout the whole film to get you from A to B. To transition from one scene to another scene, so we did like 30 or 40 of those, it was quite a lot.

Animated sequence from Tank Girl involving the tank and the jet

Rachel: You have to remember that this is pre-digital, right? You’d do it with your eyes closed now and it would be amazing! But the cost of each one of those shots, if we wanted to even have the jet flying, was killer. So I came up with the idea that we could put animation sequences in.

Andrew: I did it all kind of seat-of-the-pants improvisational with no exposure sheets, for that animation. I would spin the bed while the camera was running and do zooms up and down the column. And that gave me a lot of exciting footage, which was then handed over to the editor. And to then compensate for the craziness of that, I also did a lot of the early moves at Lumeni, and they had mechanical concepts, cranes that were computer-controlled, and they were able to do bi-packs and hold-outs and all kinds of gimbal moves, that had the smooth professional look and that was intercut with the wild stuff that I would shoot.

Look at Deadpool! Tank Girl’s the precursor to Deadpool. It just took twenty years to get there

Various drawings by Jamie Hewlett extracted from Tank Girl for use in the title sequence

The animation is one of the things that makes the film so unique. You don’t see comic movies like that, and you don’t see action movies like that, and this is both.

Rachel: The executive at United Artists who hated the film – he’d say, “I hate animation! I hated it when I was a kid, I hate it now! I don’t want to see any of this!” But we ended up doing it anyway. He said, “I still hate it!” [laughs] We still kept it in. We had that sequence in the middle and the sequence at the end. I love those sequences.

The people who dislike it say, “What a mess! You can’t do that – you can’t put animation in the middle of it. You can’t put these still panels in the middle of it.” You wouldn’t say that now. You can do anything you want now! But in those days, they would say, “You can’t do this, you can’t do that.” And any time anybody said to me “you can’t”, then it was like, well, I’m going to do it anyway!

Rachel Talalay directs Lori Petty on the set of Tank Girl, 1995.

Photograph © United Artists

Yeah. What would Tank Girl do?

Rachel: Yeah! [laughs]

You’ve mentioned before that you were idealistic when you were making Tank Girl. You thought you could break the glass ceiling for female action films.

Rachel: Yeah, I really did believe that it was going to be a huge success. That everybody was going to have the same response, which was, “Wow! We can have a female action hero! And she’s so outrageous and this is absolutely great!” And we went out there and I believed that that’s what people wanted to see. If we’d made it five years later, you know… I mean, look at Deadpool! Tank Girl’s the precursor to Deadpool. It just took twenty years to get there, and it still had a male lead!

But they made us cut it back so much. They were so frightened of it, so we had to cut it back a lot. If we had made it even five years later, by then there was South Park, you know? They’d be going, “How far can you go with this?”

At least you got to include the Shaft theme. I’ve heard that’s one of your favourite scenes in the movie.

Rachel: Oh, yeah! [laughs] Oh, God. You are just – ! [laughs] But I just love that moment!

Scene from Tank Girl featuring the title theme from Shaft (1971)

Andrew, do you have a favourite part of working on this?

Andrew: Well, I think it was just the intensity! It was basically go, go, go! Every day in January or February, we were doing something. It was pretty much nothing but Tank Girl those two months in early 1995.

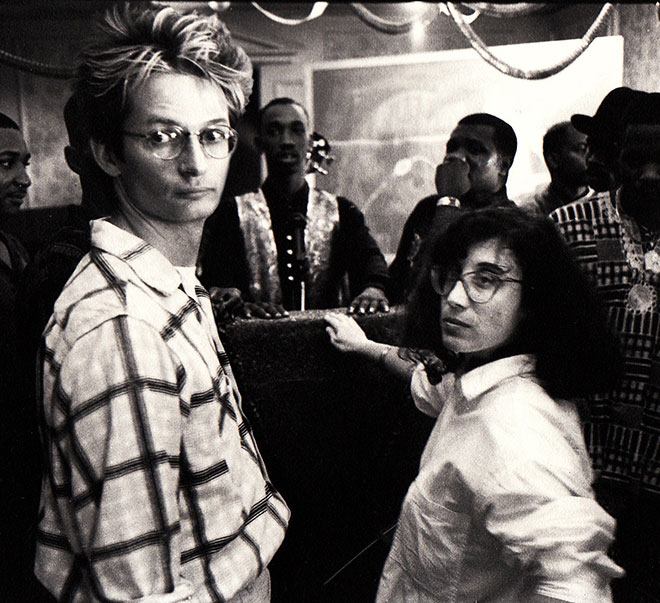

I would be running from New Hollywood or I would be shooting. To get through a roll of 400 ft of 35mm film, frame-by-frame, is pretty unusual and I did that on one 14-hour shoot. All the old-fashioned equipment was coming into play, and I was running around checking on everything and then doing my own thing. And you know, I was working with friends! Jane Simpson, who was the producer, I’d worked with her a lot. We co-directed some music videos, she had a company called Triplane, she directed a feature or two. Jane was a great producer.

Andrew Doucette and Tank Girl title sequence producer Jane Simpson in 1989, on the set of the music video for "Livin' Large" by E.U.

If we talk about title sequences more generally, what do you think a title sequence does for a film?

Rachel: It’s an interesting question because now it’s trendy not to have an opening title sequence, but in the old days openings had every credit in them. I think the best thing you can do with a title sequence – and I think probably the best title sequence there is at the moment – is Deadpool. It sets up exactly what the movie is! It’s not about who the people are, it’s how to set up the story.

In television you are using your first scene to set up the episode. I just did an episode of Doctor Who and it’s an episode that’s unlike any other – it’s 55 minutes of one actor. And we had to say to the audience, you’re going to watch something that’s different from anything you would normally see on Doctor Who. That’s what you want to set up. That’s what Deadpool did. You know what you’re in for, and it’s going to be way out there. And I think that’s what Tank Girl did. It said: This is a comic book movie, it’s unabashedly a comic book movie, and it’s one like you haven’t seen before.

If you can set up the tone of the entire movie with your titles, or with your opening, then you’ve done it. And it can be slow, and you can ease into it, or you can go, “I’m grabbing you by the balls!” I don’t think people just want to sit there and look at graphics unless there’s something individual and different. I want it to grab me.

It can be slow, and you can ease into it, or you can go, “I’m grabbing you by the balls!”

Deadpool (2016) main title sequence, designed by Blur Studio

When you think of title design, do you have favourites that you think about or like to return to?

Rachel: I’m such a Kubrick fan. I keep coming back to a lot of stuff from the ’50s. Even Austin Powers! I want it to be so different and tell me what I’m getting into.

Austin Powers! That’s a totally overlooked title sequence that no one ever talks about.

Rachel: [laughs] It’s a fantastic title sequence!

Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery (1997) main title sequence

Andrew: On TV, I always liked Game of Thrones and True Detective, they were both done by Elastic. My jaw drops whenever I see them because they hold up to multiple viewings. If you can watch it multiple times and not get tired of seeing it, then you’ve done something right. Title sequences that stick with you are really important to me.

In terms of film, Se7en has got to be the one that turned my life around. Mainly because I’d already been doing that kind of stuff! A lot of my music videos were hands-on. I mean, I would be punching holes in film, I used sewing machines in film. I’d been doing that for quite a long time, and then when Se7en came out – and frankly even that end credit crawl – I was just gobsmacked! I mean, I just watched it over and over again.

Rachel, you work in TV, but do you spend a lot of time watching TV? What are you watching these days?

Rachel: I just binge-watched a whole bunch of Game of Thrones, which is amazing, amazing, amazing. And I’ve watched Sherlock about 30 times, and I continue to watch Doctor Who over and over again. I really enjoyed Making a Murderer, the documentary.

Oh, I was watching a bunch of Shakespeare! [laughs] This is the 400th anniversary, so I just watched the entire Hollow Crown series. And oh, the Eurovision song contest! So that’s a perfect Tank Girl combination, right? Just mix Eurovision with Shakespeare and there you are! [laughs]

Tank Girl (1995) end credits sequence

Rachel: It really is shocking that it’s 20 years later and it’s only now that things are starting to change. I really did think Tank Girl was going to change everything and would prove that women could be action heroes. That was the pinnacle of women being employed as directors. That was the high point. It crashed down after that. And so many wonderful women directors I know were crushed and just stopped in their tracks from 2000 to 2014. The changes are only just starting. I mean, now that the ACLU has become involved and spoken to the EEOC about the problems, it’s the first time I’ve seen women speaking out again. There’s some optimism about change. It’s the first time I’ve felt optimistic about it in a very long time.

It seems like it goes in cycles. With Thelma & Louise, Geena Davis has said that people were telling her constantly that it was going to open the door for women-led films! But that didn’t happen.

I’d like to remake it! I’d like to make the sequel. The Deadpool-style sequel of it, where we could really push the envelope

Rachel: Yep. That was right around the same time, in the ’90s. Exactly. Everyone was like, “It’s going to get better, it’s going to get better.” And then the doors just slammed. And you were told, “Never talk about the problem. It’s a surefire way never to get hired, if you ever talk about the problem or you ever make a fuss.” And you go, “Oh-kay….”

Then later on, you see it’s actually illegal to be told that. All these issues are actually illegal. It makes you feel like it’s your fault – your film didn’t do any business, so of course nobody wants to hire you. Then you look around at all these men who failed, who had plenty of failed films, but still got their next opportunity. And it is not without a little bit of bitterness that I say: I never made a feature film after Tank Girl. But I’ve been incredibly fortunate that there was never a year I didn’t get work.

Would you ever want to re-edit Tank Girl, make a director’s cut or something?

Rachel: I mean, of course I would, but really I’d like to remake it! I’d like to make the sequel. The Deadpool-style sequel of it, where we could really push the envelope and do the things that it could be now. I would like to make it in the same way that George Miller made Fury Road, which was my favourite movie from 2015. I’d like to make the real version of it that you could make now. I might not be young and cool enough anymore.

You think George Miller was cool? [laughs] George Miller wasn’t cool!

Rachel: [laughs] He spent 15 years putting that sequel together! And God, it’s so right, with the right people. And I know a huge amount more about filmmaking today than I did then. The issue really is that I would like to have Jamie and Alan embrace it. I wouldn’t really want to do it without them embracing it. All in all I’d love to figure out how to make that happen.

Rachel Talalay (center) directs on the set of Doctor Who with Peter Capaldi and crew.

Photo © BBC.