How do you cover nearly a century of sand, oil, and blood in less than four minutes? PIC Agency’s titles for The Kingdom do just that, giving viewers a geopolitical crash course in U.S.–Saudi Arabia relations that contextualizes the events depicted in the 2007 action thriller.

Using a combination of infographics and news footage, this illustrated clash of cultures efficiently fills gaps missing in the viewer’s knowledge of the region, its people, and its relationship with the West. A less inspired approach would have been to deliver the facts through a dry, text-only prologue; instead, the sequence envelops viewers in a sandstorm of charts and details. Before you can fully register one fact, you’ve learned two more. Acting as a primer, a sort of CliffsNotes for Saudi Arabia, the sequence briefs us for entry into The Kingdom.

A discussion with Main Title Designers PAMELA B. GREEN and JARIK VAN SLUIJS of PIC Agency.

So, how did The Kingdom come to you? What were you guys doing in 2007?

PG: I think we were doing some movies for Universal.

JVS: We had finished The Bourne Ultimatum and Cloverfield.

PG: Yeah. We had done Fantastic Four and everything was predominantly very graphic. We knew about, you know, stock footage... but nothing like this. I guess we can tell you the story. We had done Van Helsing previously, before starting PIC, with an executive at Universal named Sean Stratton. He called us, and he said, “I think you guys should come in for The Kingdom.” And I said, “Oh, that's Peter Berg. Wow, okay.”

Peter Berg is an American actor, film director, producer and writer. At the time, he was known for directing films such as The Rundown (2003) and Friday Night Lights (2004). He also developed the television series Friday Night Lights, which was adapted from the film he directed.

In this town people already have relationships, and for us, we were kind of the underdog. But sometimes that's the best because people don't expect you. There were five companies and us. I don't even think we had a notebook, we were so nervous! We just sat there like students. Peter was telling us that he wanted a sequence to establish a relationship between the US and Saudi Arabia. He wanted it to feel like a story that would be told by a grandfather and wanted to make it very compelling and memorable – and that was the assignment.

Did he have this idea for the titles right from the beginning?

JVS: No, actually the original idea was to have all this exposition first – a story about oil and Saudi Arabia and the United States. There was a scene in the movie where Chris Cooper and Jamie Foxx are in an airplane flying from the US to Saudi Arabia. It was a long flight, so I guess all of it could be explained, but that would be boring. It was important the viewer know and understand the history, understand why the Americans were there, why Aramco – the American oil company – was there. So, they decided on a title sequence to explain it.

—Pamela B. GreenYou could be the most amazing Picasso out there, but if you don’t have the right opportunity, forget it.

So, how did that first meeting go? Who were you up against?

PG: The usual suspects. There was one right after another. It was like going to a doctor’s office.

It was a first for us in this category – telling a story using all stock footage and voice-over. I mean, we came from movie marketing, but hadn’t done anything as involved as this. When [Peter] tells you he wants something interesting and that he wants it to tell a story, you know, you don't think about what you're going to be using! You just try to figure out the best way to tell it so it doesn't become a history lesson.

JVS: I don’t even remember who went before us, but we did hear Pete’s talk – screaming his presentation to the previous company – so we thought, okay, this is gonna be fun. I think he was already tired by the time he got to us. Basically, we got homework. We had to do a lot of studying, watch a lot of Frontline videos, read books. I think we even got a book called The Middle East for Dummies.

It was great because it was such a learning experience. Initially our approach was to do something completely graphic. We had an idea about what it would be, the color schemes, and so on. We thought it was going to be one long graphic sequence. We presented one long, evolving board that was completely graphic.

The Middle East For Dummies

Craig S. Davis

Also, we weren’t given a script, we were given a couple of key points that he wanted to touch upon, but mostly we built our own script.

So, in this pitch meeting, you didn’t present anything – you just got your homework?

JVS: Yeah.

So he was pitching to you, in a sense?

JVS: Pretty much, yes. Debriefing us.

PG: Well, but – just to be clear on that, too – I think a lot of companies go in with ideas of what they think it should be… but we listen. I think that’s number one: Listen and be low key, and then come back in with your ideas.

JVS: Yeah, we believe that without a real brief, without understanding what the film needs, it’s not respectful to give ideas. And in this case we didn’t know anything!

PG: Right, and the studio might have done some testing which showed that the audience wouldn’t get the movie without that setup. So, he was telling us what he was looking for, but he was also kind of resistant because he’s a storyteller and in telling your story you don’t want this extra layer on top unless it’s gonna fit.

We were just excited we got in the door. It all starts with opportunity. You could be the most amazing Picasso out there, but if you don’t have the right opportunity, forget it. And that was due to Sean Stratton. Even though there was competition, opening the door is key.

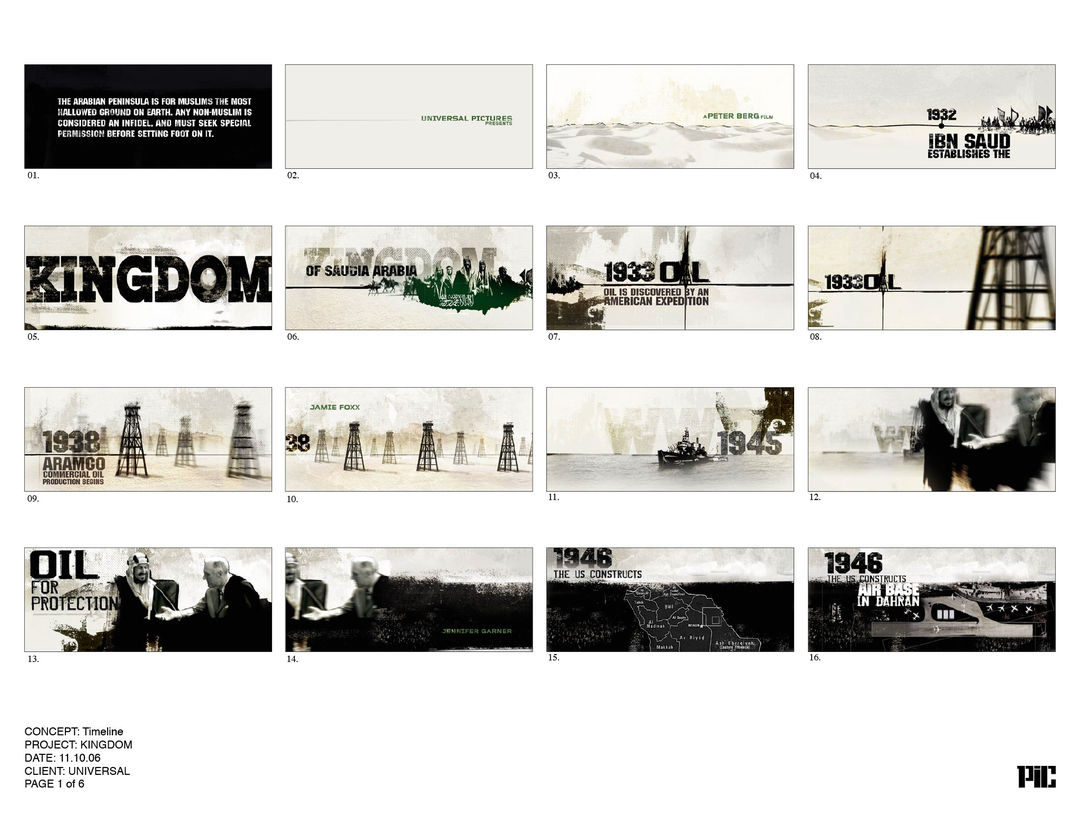

PIC's initial 91 frame storyboard

Talk about the second meeting and presenting your initial board.

PG: It was myself, Jarik, and Stephan Burle, who is an amazing designer.

JVC: Stephan Burle, yeah. Amazing art director who did most of the boards and Gary Herbert who did most of the 3D animation. He was sort of a perma-lancer back then. We presented the longest board to date then, and then the animatic.

PG: But we couldn't find the right stock because we just had no idea where to go. I only knew Getty and Corbis, so we had no idea how to try to find some of this stuff, especially video. But I found a little piece of footage, and we had to blow it up. It was just this little Canadian network square, an animation test.

JVC: Right. We didn't have any video! We had just animation, but we knew we were going to use newscast voices and audio, newspaper clippings, all that fun stuff.

1st animatic

And, basically, there were two pivotal points in the story. One, when they found oil in Saudi Arabia when they were actually looking for water. Two is, of course, September 11th. From the get-go we knew that point was going to be important and also the biggest challenge because you could go through a whole barrage of images but when you get to September 11th, it’s still effecting. We needed to give the audience the space to interpret it. What we ended up doing was animating the section of the boards that take us from Osama bin Laden in the ’90s, through the ’90s, and then ending with September 11th, 2001, and instead of using images of that, we cut to black. And then we just fade up, seeing Manhattan from overhead. We step back from the event. We didn't want to glamorize it or use it too much. We wanted to be respectful.

—Pamela B. GreenAnd I called the FBI, and Universal was like, "Don't ever call the FBI!"

PG: We wanted to keep the emotional part under control, because there's a lot of violence that gets shown pertaining to September 11th, and it’s important to be tasteful.

JVC: So, our animatic was actually built around that. The moment we saw it for the first time in-house, it just worked. It took on a life of its own. It’s really scary when that happens, you know! We thought, yeah. This is going to get us the project. It hits you like nothing else. And that has to do with the events I think, the gravitas there.

The important thing is to see the history and then go to the more analytical aspects, which is the oil producers. You see that Saudi Arabia is the biggest oil producer in the world.

PG: Not anymore.

JVC: Not anymore, but back then! And it’s shown graphically. Then we show the United States as the biggest oil consumer, and then a graph, which is impressive, but ultimately just cold numbers, just analysis, then to the World Trade Center in a flash. So you connect that information emotionally to the events and something that you've experienced. I think that happens throughout the sequence in spots, but that’s the strongest instance.

PIC's refined 9-page 130-frame second storyboard

So that was the animated part of the sequence that you showed to Peter and the producers?

JVS: Yes. The producers, one of whom was –

Michael Mann is an American film director, screenwriter, and producer. At the time, his major films included Heat, Collateral, Ali, and Miami Vice.

PG: Michael Mann!

Haha, wow.

JVS: It was very intimidating, to say the least. And he had a very strong...

PG: Opinion.

JVS: About what it should be and what it definitely should not be.

What did they say?

JVS: Well, what stuck was that they wanted the modernity of Saudi Arabia to come across. And that this idea of modernity is what led us to this point, this clash of cultures. For a lot of people, it was easy to look at the Middle East and think of everyone sitting on a camel, you know, but it has some of the most modern cities in the world.

PG: Oh, and the FBI was an issue as well, I think. So, we went in, and went through that long board with Sarah Aubrey, Peter Berg, Scott Stuber, Michael Mann, Kevin Stitt, and then showed the animation test. And you know, sometimes people smile, like, "Wow, this is compelling." Or sometimes they have a…

JVS: ...a poker face on.

PG: Yeah. But Peter said, "I don't care what anybody says, this is great." And he left the room.

JVS: Peter had decided that he wanted more footage. We had to do even more research, and then we just basically started cutting. Actually, we still did not have the job yet!

PG: No, haha. We did one more shot at it where we took footage from documentaries. Mostly the Frontline ones and then we presented again. We were nervous, because we really wanted the job.

2nd animatic with additional news footage

This is your second presentation, then? You used documentary footage as well as your graphic treatment.

PG: Yes. And then the waiting game. We got the job. Of course, we didn't know what we were in for! It was a search to find the best footage. It becomes an addiction, a kind of detective work, contacting people that might have shot things. We found this guy who grew up in Saudi Arabia, whose father worked for Aramco, and he had some 16mm footage. In the piece, where they're playing football, Universal agreed to pay for that footage to be transferred, so we got to use it.

And we called the Saudi Arabian ambassador, trying to use him in there, negotiating the clips. It was from another film, so we had to find the director. She was in Egypt at the time and we had to get her permission and permission from the producers. We called a brother who worked in Saudi Arabia for Al Jazeera. And I called the FBI, and Universal was like, "Don't ever call the FBI!"

Stock footage sources breakdown

And every time we would find a cool shot, you would hear cheering from one side of the room to another.

JVS: It was like finding gold, you know?

Did you have to clear all of that footage?

PG: Yeah. Actually, what happened was the movie was done but the release date was changed. That was a blessing because it took nine months of clearing, finding, calling Saudi Arabia. I even asked Pete to call the Saudi embassy about using stuff in the film.

Nobody claimed ownership over a lot of the footage and it was just good. Like when they're sitting at the racetrack – you can't not put that in there, it's amazing. It engages you to understand the difference between Saudi Arabian culture and American culture. We didn't want it to feel like something seen on TV. We wanted it to feel like something special, unusual, something that fit Peter's film.

Right. It helps it's in 2.35:1. You're immediately out of the 4:3 or even the 16:9 ratio of TV.

PG: There was a lot of surgery that was done to that footage to make it look good. It was very difficult to format that footage that so it would work. That was one of the biggest concerns for the editor.

JVS: Yeah, definitely. We decided to treat all the footage a certain way because it was coming from all over: 8mm, 16mm, video, some digital. For example, there would be a bit of footage from the ’70s shot somewhere on film, then transferred to PAL in Europe, then transferred to NTSC in the States and digitized, so it’s got all these layers of scan lines and loss. We tried to use this to our advantage or we’d clean it up – a combination of both. In some cases, actually, the footage was too clean so we had to dirty it up!

PG: One of the scary things we learned about stock footage is that some places have no documentation of where some footage came from. The source gets lost. There was footage of this Mujahideen guy with a cigarette in his mouth and the stock company said, “I'm sorry, we're not going to be able to find that.” But I insisted and finally he found it. We were so happy. It was just an arresting image and it really added to the story.

PG: The other thing that was an issue was that the Osama bin Laden parts were exclusive footage for CNN. Thank God I had actually lived in Atlanta before and worked with CNN and Turner. That helped release that footage as well as the Larry King stuff, because they would not do it otherwise.

—PAMELA B. GREENNow people keep asking us, “Can you do this like The Kingdom?” And we say no. Because it was perfect for just that time, those people, and that budget.

Another thing was Will Lyman, for the voice-over. We wanted the best so we had to negotiate with his agent to make sure that he would agree to it, which was a very big deal because he is the voice of Frontline. That was an unusual request, but we were like why not get the best? And we did.

What about the music? There’s those sort of opening bars of music and then it goes into a kind of bass line.

JVS: We actually used another piece of music for most of the cut. And then, Danny Elfman came in to score it and do his thing. But the tempo remained the same.

PG: It was funny. Jarik, having edited the piece, had very specific areas where effects would hit, and they weren’t hitting properly anymore. I was a lot more vocal back then. I still am, but it’s different. I think I called Peter and I said, 'It doesn't sound the same. There's some stuff missing. We've gotta have this stuff here.' He knew we wanted to make it better so he let us make some adjustments.

And wasn’t a lot of this story being affected by events happening in real-time? How did you deal with that?

PG: Right, I think Saddam Hussein was killed while we were cutting it. We had a section of Saddam Hussein dancing, so that was really awkward. So, we had to make a lot of political decisions to keep a balance. You can still tell a story and portray conflict and violence without having to show those kinds of images specifically.

Special stock footage from an ARAMCO employee

It’s interesting that it works so well and has such a clear path given how long it is and how much information is packed into it. Besides being a historical graphic sequence, it’s also a title sequence, so you have to have all the credits in there, too.

PG: It’s funny about those titles. Legally, today, those titles would have to be on screen longer. Anyway, you can read them, and that's what’s important. Even though it’s long, the credits help us get away with it. If they weren't there, it would take away from it.

Right, they’re a visual cue. As you get closer to writer or producer or director, as a viewer you're aware of it wrapping itself up.

PG: Exactly.

Not only that, but the sequence was used to market the film. It was online, in the release, it was everywhere in the media. I mean, we were written up in the Wall Street Journal! It was crazy. And it was an unusual sequence to go in front of this movie because it’s an action film!

Now people keep asking us, “Can you do this like The Kingdom?” And we say no. Because it was perfect for just that time, those people, and that budget. We can do things like that stylistically, but we don’t want all of our work to look the same. This has actually hurt us as a company because people want to typecast us. But if we just did that we wouldn't grow.

But we kind of owe Peter Berg for this because it really did put us on the map and gave us new avenues. It was The Kingdom and Bourne Ultimatum that really did it for us with ad agencies, opening the doors. It got Robert Redford’s attention and led to us working on his movies.

You are still asked to make things look like The Kingdom? It's been six years.

PG: Yes. It doesn't stop. I mean we did Red Dawn, so we did do it once more. That was the history between the US and China and then they realized they couldn't do that. It was history between the US and North Korea. We actually faked a lot of the stuff and then it came true afterwards which was really freaky...

Has The Kingdom become one of the projects that you're most proud of?

JVS: Yes, Kingdom is definitely one of the ones we're most proud of. I think at the end of the day, the reason that sequence in particular works is because the story is not told through one line all the time – it's not just voice-over, it's not just graphics, it's not just stock footage. It passes the baton a couple of times throughout the sequence so that the audience doesn't get hypnotized by seeing or hearing just one thing.

And also, we were able to have creative control until the end.

PG: The creative aspect is important, because often people futz around and then it turns into something else. That kind of storytelling is our roots.