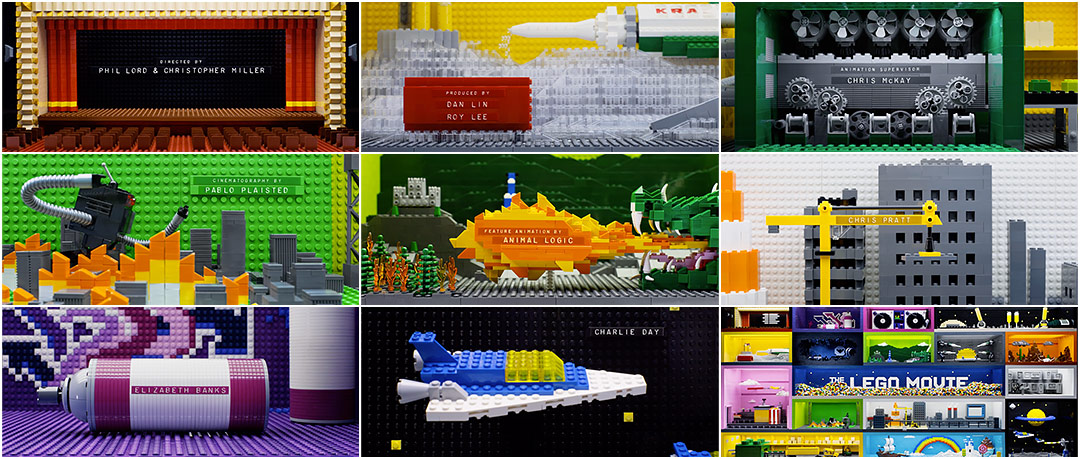

Take a stop-motion animated journey into the world of The Lego Movie, a side-scrolling flight through a series of brick-built dioramas recreating scenes and settings from the film. It seems a crime that the deceptively simple building blocks at the center of this adventure had not been used in a title sequence until now, but Alma Mater does the Danish plaything justice here, cleverly exploring its full potential as the credits roll.

From the dark recesses of the Batcave and the far reaches of outerspace, to the pirate-filled high seas, the rainbow-infused insanity of Cloud Cuckoo Land, and the arid plains of the Wild West, each DYMO label credit is integrated perfectly with its backdrop. Brick by brick those little plastic pieces fall into place, and as a dangerously catchy Tegan and Sara anthem blares the camera pulls out to reveal the full scale of one seriously fantastic LEGO creation. Everything is awesome!

A discussion with Creative Director BRIAN MAH, VFX Supervisor JAMES ANDERSON, and Executive Producer KATHY KELEHAN of Alma Mater.

So, how did this project begin? What was the first meeting about this sequence like?

BM: We were initially contacted by the directors, Phil Lord and Chris Miller, to discuss the project in December of 2012. We were extremely excited. Legos are such a nostalgic, creative, and treasured toy from our youth; the thought of creating a main title using them inspired endless possibilities! On top of our enthusiasm for the subject matter, we love working with Phil and Chris, two great collaborators from 21 Jump Street.

The first meeting, in early January 2013, was really exciting on many levels. Everyone involved had such passion for the project. We met at the Animal Logic offices, and were surrounded by concept sketches, bowls of Legos with assorted creations strewn about, and a shared sense of enthusiasm for all of the creative avenues that could be explored.

Director Phil Lord at the LEGO offices.

Still image courtesy Warner Bros.

So, why decide to make an end title sequence, and such an elaborate one, at that?

BM: During the meeting they explained that main-on-ends felt right for the narrative flow of the story. It’s very rare to meet about a main title over a year before the delivery but they wanted to get the process started because, while the The Lego Movie was created entirely in CG, they liked the idea of using actual stop motion for the end title. We loved the idea, but we also knew right off the bat that doing a stereoscopic sequence comprised of 2½ minutes of stop motion was a pretty elaborate endeavor!

KK: It was really refreshing to be brought in so early in the process. So often we'll have a 6-8 week production schedule which runs right up to the moment the film has to be finished. We watched the entire film in its state at that point, which, even though it was probably 90% drawn storyboards, was hilarious.

BM: Throughout the meeting, Phil and Chris discussed how the global Lego culture and enormous fan base had been a source of inspiration for the film. We talked about sites like brickfilms.com – a site full of fan-made stop-motion Lego films – and we discussed how that "handmade" charm could really play a big part of the end title aesthetic.

Conceptually, the brief was very open. We discussed everything from building a fully original sequence, to creating a montage of entirely crowd-sourced material. The primary goal was to create a piece which felt fresh but distinct from the film itself.

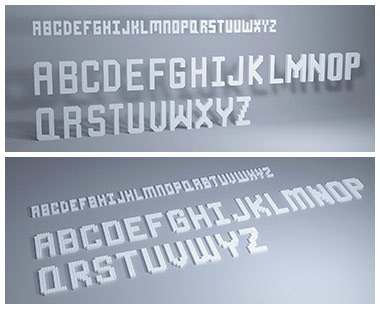

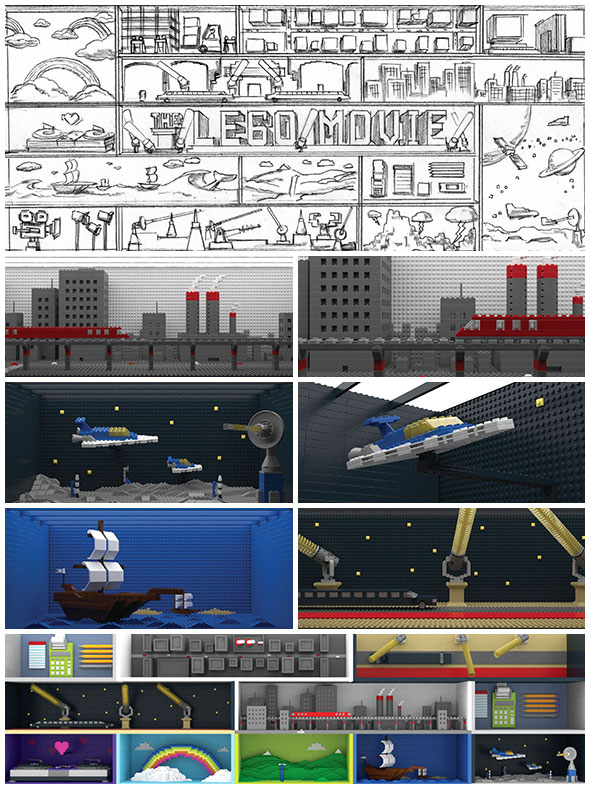

1st round type treatment concepts

How did you start to develop the initial concept?

BM: We began by focusing on the typography. Since this was a title sequence, we loved the idea of using the Lego pieces to construct the letterforms of each card. We figured that we could start there, and then design a world around it. The tricky part of working this way – beginning so far outside the delivery date – was that there wasn't a finalized credit list yet!

We needed to start somewhere, so we began with the credits that we knew would be included like the directors, producers, cast, and worked from there. We created a series of alphabets at various scales for names and designators until we found a combination that we liked. We landed on a letterform design for the names which was about five inches tall. Unfortunately, given the long lengths of some of the names in the sequence, this meant that each scene had to be about 70" wide.

We began creating concept drawings of themes, objects, and environments contained within the film which could relate to each credit or title. We liked the idea of typography intertwined with the landscape around it, and a landscape that could be filled with content relating to each character. As we designed each title, we would constantly assess the average number of Legos needed for the construction of each scene. The sheer mass of the sequence started to become apparent as each scene was taking between 8,000-10,000 Legos per card at that scale. Knowing that it would take around 30 cards to complete the sequence, we were looking at about 300,000 Legos!

1st round 'typographic' concept boards

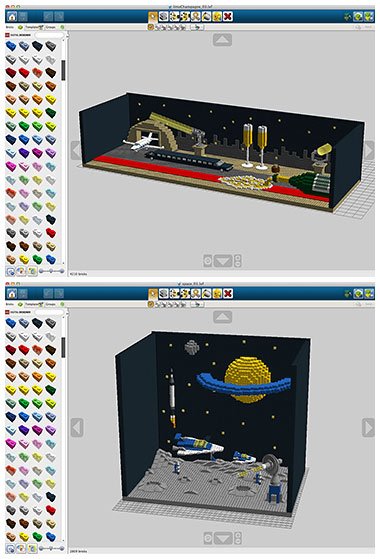

JA: To create the presentation frames, [this sequence] was first designed in Lego Digital Designer. The problem with this software is that the render quality is very low; sculptures look more like flat-shaded wireframes. We knew we wanted to show the directors something much closer to the look we were going for. Using Lego’s proprietary software, we imported the LDD files into Maya to texture, light, and render stills to show Phil and Chris.

Tell us a little about Lego Digital Designer.

BM: It’s a free program that anyone can download online and it played a huge part in our design process. It's like a user-friendly CAD program for building with Legos. It was originally created so that people could virtually build an object, then export a shopping list of which parts they needed to order to build it in real life. Once you get the hang of it, it's a really fun program to use! It’s very realistic – everything you build literally has to be created the way you would build it in real life, brick by brick. It won't allow you to put pieces together that won't connect in reality. This made it a double-edged sword, in a way.

Lego Digital Designer interface screenshots

It was a great way to plan out designs, test various color palettes, and create a schematic of the construction of each scene. It was also the only way we could get a specific parts list and price out the costs of the materials for accurate budgeting. The downside was that due to the "brick by brick" nature of the interface and the very specific relative scale of the Legos themselves, revisions were very difficult.

For example, say that you constructed a sphere – which are surprisingly difficult to create, by the way – and you had spent a day building it in LDD, finally finishing it and placing it into your scene. Then, you thought it would look much better if it were 20% smaller. In almost any other program I can think of, be it Photoshop, Illustrator, After Effects, or any 3D software, you could scale down that element 20% and be done. In this case, however, you can't scale anything, because Legos are a set size! You have to rebuild that sphere from scratch at the new desired size. Multiply that process by every object that was created for the sequence and you can see how time-consuming that became.

Wow, yeah. What kind of feedback did you get, and how did the cubby design progress?

BM: In our first presentation, two key pieces of information shaped the progression of the design. While everyone responded well to the "themed" nature of these typographic scenes, the large scale of the execution seemed to take away from the lo-fi, homemade charm that would differentiate it from the film. Having each scene so big added a finer resolution to the bricks, and without seeing the blocky nature of the aesthetic, or even the iconic pegs on each block, it seemed to take away from the concept's relatability. The second piece of information, which was huge, was that the credits list wouldn't be locked until late in the schedule. We would need the ability to make adjustments or even add names right up until the end. This made shooting a stop-motion sequence based on physically built typography virtually impossible! We left the meeting feeling determined. Despite the need for credit adjustment, we wanted to preserve as much of the practical nature of our methodology as possible, while containing the scale for both aesthetic and production purposes.

2nd round type treatment concepts

We went back to the studio and immediately began trying to see how small we could build the scenes. I wanted to see how few bricks I could use to build a city train, or a bat, or a cop car. I think we made it in six pieces. The results instantly felt far more charming. You could appreciate the unique details of each individual brick, rather than having them get lost in a mass of fifty pieces. It was a great example of "less is more." This shift in thinking allowed our scenes to go from an average of 10,000 Legos to about 3,000 per scene.

*DYMO Corporation is an American company that manufactures handheld label makers and label printers. Dymo Industries, Inc. was founded in 1958 to produce handheld tools that use embossing tape.

We also pursued the idea of using old school DYMO labels* for the names in each scene. This would allow the type to still feel practical and integrated without dictating the scale of the scenes. We planned to add them digitally after the shoot, allowing for the most flexibility. With this new approach, we prepared our second presentation. In this round, we showed two concepts for how these scenes could be connected.

One melded all of these varying themes into one, long continuous landscape. We played with a whimsical sense of scale for the objects – so, a giant lollipop might sit next to a tiny castle. The idea was to allow each theme to "cross pollinate" with others, creating a very diverse horizon of fun subject matter.

2nd round ‘seamless’ concept boards

The other concept was to intentionally contain each theme into its own four-walled diorama. It would appear like a series of juxtaposed cubby holes, each housing a different piece of content or perspective. For instance, a profile view of a city could be right next to a cubby with an aerial view of the same city. This design would allow each theme to be more succinct and specific, while still providing the viewer with a fun journey from one to the next. In the meeting, everyone was unanimously drawn to the diorama concept; the fact that there were physical divisions between the various worlds seemed to relate nicely with the plot and spirit of the film.

2nd round ‘diorama’ concept boards

So how did you progress through the actual building process?

BM: Once we landed on the specific direction we were going to produce, it was time to flesh out the concept for the entire list of credits. We created lists of themes and objects of significance in the film, and selected those with the most potential for Lego translation and animation. One of the designers on the job, Ford Spencer, had a real knack for the Lego Digital Designer program, and Legos as a medium in general and he designed many of the items that made it into the final sequence. What makes his work even more impressive is that a lot of the pieces he designed were not only structurally sound and visually striking, but functioned from an animation perspective as well – so, a factory machine would have functioning gears and pistons inside! He was an invaluable asset to the team.

As cubbies were completed, we would present them to Phil and Chris, making sure everyone was on the same page. They would help us brainstorm new concepts and throw out ideas for little inside jokes that could be peppered throughout – for instance, Animation Supervisor Chris McKay has a lot of Catwoman tattoos in real life, so there’s a little Catwoman helmet near his credit.

*Previsualization (also known as previz, pre-rendering, preview, or wireframe windows) is a function to visualise complex scenes before filming

JA: We imported every cubby from the Lego software into Maya to begin previs*. Knowing the sequence would be stop motion and stereoscopic, every detail needed to be planned out in Maya prior to the shoot. Working with a talented team from Proof, we created cubbies in Maya which were dimensionally accurate to their real-world counterparts, allowing us to block out all of the primary animation and camera choreography for each shot. Not only did this give us the flexibility to explore different creative directions, but also provided precise measurements for camera travel, lens focal length, and even stereoscopic interaxial distance.

Previz render examples

Every camera move was designed to be linear and shot using a motion-control slider and since the shots were so macro, the level of precision required was insane. For some shots the camera travelled only a few millimeters over several seconds. It seemed so ridiculous at first that we had to double and triple-check our measurements in Maya to be certain! Since we already designed the shaders and lighting during the pitch phase, we joked that all we’d need to do was hit “render” and we could be done with the sequence. Of course this wasn't really the case, but it's crazy how far we ended up taking the CGI just for the pitch, design, and previs phases.

BM: Simultaneous to the previs, we had begun feeding digital files to the builders at the LEGOLAND Studios Model Shop. They were responsible for taking our designs and building the finished models, brick by brick. The build team, led by Ryan Ziegelbauer, was truly amazing. Their vast knowledge of Lego inventory and history was crucial to this process going as smoothly and efficiently as it did. We made sure that everyone involved in the shoot, the build, and post were in constant conversation, preventing any surprises down the road.

Building process at the LEGOLAND Studios Model Shop

Throughout this process, the builders were coming up with really useful ideas on how to make structures stronger, more modular, and more animation-friendly. They would help create innovative pieces for replacement animation, simplifying the way a curtain might build up, or a stream of mustard might flow out of a dispenser and onto a hot dog. They were very resourceful, coming up with creative solutions for parts that weren't manufactured anymore as well, whether it meant finding a visually pleasing alternative or personally tracking the piece down in online auctions or fan collections.

And what about the actual animation?

For the stop-motion shoot, we collaborated with the talented artists at Stoopid Buddy Stoodios. These guys were fantastic to work with as well. Ethan Marak led the animation team, and was constantly finding ways of making the sequence stronger. As the previs was completed, we gave each shot to Stoopid Buddy, so they would have a "to the frame" template for shooting. Ethan and his team brought so much to the table regarding the animation and choreography of each scene. He even set up a little green screen set on his desk for testing ideas he had, and would show us proposed animation cycles for various elements in the scenes.

Stop motion tests

With the help of his DP, Helder Sun, the team did a great job matching the precise camera work we had established in the previs, while bringing the scenes to life with animation and cinematic lighting – which isn't easy on miniature sets with super intricate and reflective plastic parts!

We shot on their stages for about a month. Each day, I would meet the team on set, review the previous day’s shots, and discuss our goals for the next lineup. I was always so impressed by everyone's enthusiasm and focus. Some of the shots were very complex, and required moving over a hundred bricks for each frame of animation, but once you got to see these pieces move, the shots had so much charm and personality, it was obvious that all of their hard work had really paid off.

When did the music come in?

KK: In the first meeting, the initial rough cut contained an early version of "Everything Is Awesome." It was such a fun and catchy song, and a major theme of the film, that we always had a feeling the sequence would be set against it. But it wasn't until the previs stage that we started to get the mixes that Mark Mothersbaugh and team were working on. We loved the last minute addition of The Lonely Island to the track.

How many pieces of Lego in total did you end up using? Were there any custom pieces you needed to design or order?

BM: We used more than 60,000 pieces to build the sequence. We wanted to keep it very true to Lego, so we didn't use any custom or non-Lego pieces, but we did purchase the entire North American stock of certain pieces!

For instance, in one of the scenes, we created these Klieg lights which used translucent yellow discs for the beams of light. Evidently, that disc, in that color, was a discontinued piece from an old space set. The builders were dedicated to maintaining the intended aesthetic, so they went on eBay and brick resale sites and basically purchased every disc being sold in the country to construct the design. Somewhere there’s a kid right now trying to find that piece for a space station he is building and having a really hard time; basically, we're responsible for ruining that kid's day.

Stop motion animation time-lapse

KK: The people who collect Legos are a very interesting lot. For example, one collector who provided some of the pieces had run out of storage space in his house, so he was storing Lego under his floorboards! He had even gone so far as to make himself a map showing where the various pieces could be found under his floor.

Tell us about some of your favorite moments from this production.

BM: I loved seeing our designs built for the first time. That gratifying moment when our LDD digital files were translated to tangible objects. All of a sudden we had these great little sculptures that were in physical space. I think that was the moment I felt like the sequence was really going to capture the playful charm that Lego embodies, and we were hoping for.

What were some challenges you encountered?

BM: Time ended up being a big challenge for this job. It's funny, when we began the project it seemed like we had all the time in the world. We were starting a year ahead! Every step of this project, however, was very time-consuming. Each phase required patience and effort, from working within the technical limitations of the LDD software to assembling the right teams for each phase, to sourcing and building the intricate sets out of thousands of Legos, to the tedious nature of shooting frame-by-frame, brick-by-brick, stop-motion animation. In the end, the schedule became much tighter than we originally anticipated.

JA: Also, the title size requirement was made even more challenging because we were working in a physical space with predetermined Lego and label sizes, so there was no way to cheat anything. Planning where to place each credit within the physical scene and moving the camera in 3D space to ensure the credits would all end up the exact same size on screen required the previs team to be very exact and detail-oriented.

Stop motion animation time-lapse of final title reveal

KK: Plus, during previs, there were the usual last-minute additions of credits, but these had more of a serious impact because they added running time to the sequence. It grew from the original length of 2½ minutes to nearly 3 minutes by the time we were done. This required another full week of stop motion shooting days, which combined with the subsequent post time, really squeezed our schedule.

How big was your production team?

BM: All in all, we had about 50 people. Each phase was comprised of a great group of very talented people. I can't say enough about the team we were able to put together on this project; it literally wouldn't have happened without all of them committing themselves to creating such beautiful work over many long days and nights. Our design and post-production team included 11 people. There were also three previs artists from Proof, 26 Lego builders from the LEGOLAND® Model Shop, and a team of 14 from Stoopid Buddy, dedicated to the stop-motion animation.

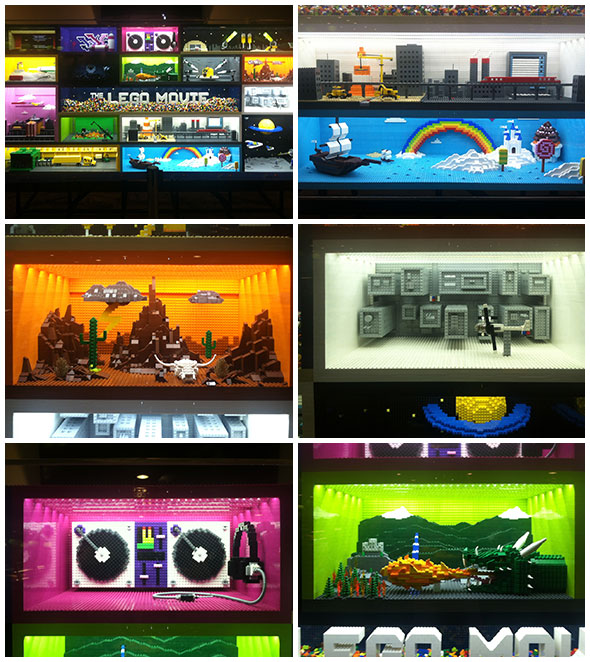

Final end frame on display in the lobby of the LEGOLAND Hotel in Carlsbad, CA

Still images from The Brick Fan.

What’s your history with Lego? Did you play with it when you were a kid? Do you still collect it? Do your kids play with it?

BM: I played with it constantly as a child, my family had a big bucket of various pieces, and I would spend hours constructing little forts and vehicles. As a creative who loves building projects from start to finish, I wonder how much those experiences influenced me. Nowadays, I do not collect them, although we do have enough pieces left over from this project to build a full-sized Smart Car...or maybe a La-Z-Boy chair, or a Smart Car with a La-Z-Boy chair inside.

Does this sequence still exist as a physical object or was it disassembled after you finished?

BM: Yes, it still exists! The final end frame of the sequence measured about 10-feet wide by 5-feet tall when it was all constructed. To help support the weight of so many fragile components, the builders at LEGOLAND designed this extremely precise shelving system which they fabricated out of steel and built on casters. This creation was crucial for allowing us to shoot the end scene practically, but it also made it so that this cool compilation of the various end title scenes was both portable and structurally sound for display purposes.

KK: We showed images of the piece to Warner Bros. and LEGOLAND, and they immediately saw its marketing potential. Directly following the shoot, it was transported to the lobby of the LEGOLAND Hotel in Carlsbad, CA, where it will be on display all this year.

Brian Mah's 30-foot homemade champagne bottle

What excites you outside of design?

BM: Whenever possible, I really enjoy getting off of the computer and building things with my hands. I recently built a 30-foot wooden champagne bottle for a party in my backyard. It had a built-in bubble machine, which would rain down on the guests throughout the night. I think I get that from my father; he was obsessed with tools and loved "projects." Like him, the more ridiculous a project seems, the more appealing it is to me.

Support for Art of the Title comes from