In the opening title sequence to Amazon’s 2022 science fiction series The Peripheral, towns gleam and shapes stretch, sweeping in strokes of burnt gold, slate grey and steel blue, like a machine’s idea of a landscape painting. It’s a little cyberpunk, a little Friday Night Lights, and a whole lot of fizzy, glitching tension.

The Peripheral is centered on 3D print clerk Flynne Fisher (Chloë Grace Moretz) and her veteran brother Burton (Jack Reynor), rural gamers who are thrust into a web of possible futures, surveillance and subterfuge. It's the first screen adaptation of a William Gibson work since the ’90s – think 1995's Johnny Mnemonic or 1998's New Rose Hotel – and its intro alludes to a journey, moving the viewer from a thriving, populated metropolis to one haunted by ghosts of its pasts and futures, all melded across time and space. The sequence walks a fine line between small-town warmth – with amber light streaming from home windows and open doorways – and a techno-cool aesthetic, the pixels scraping smog-shine and electric blue across the screen. A gossamer-like tether stretches from one part of the world to another, causing ripples as it travels, landing in a London full of looming statuesque forms.

The evocative opener is the latest collaboration of Emmy Award winners Patrick Clair and Raoul Marks, working under their studio Antibody, who previously created the slam-dunk titles for True Detective (2014), Halt and Catch Fire (2014) and Westworld (2016). Combined with a mysterious and menacing theme by composer Mark Korven, who also scored 2022’s The Black Phone, the sequence is a solemn and sleek introduction for this tech-tangled thriller.

I reached Patrick Clair via Zoom to get the lowdown on this unique aesthetic and the machine-learning software they used to create it.

A discussion with Creative Director PATRICK CLAIR of Antibody.

How are you, Patrick? It’s lovely to see you again.

Patrick: You too. It’s been ages! I’m good, I’m really good. Enjoying life down here in Sydney.

You are still a pretty tight team at Antibody, right? You and Raoul, your two producers and then you pull in freelancers?

Patrick: Right, we pull in freelancers from all over the place. Often the main titles end up being me and Raoul, ’cause we’ve got a good yin and yang happening. We complement each other. I’m more big picture but he’s excellent at details. I feel really lucky to have found him.

Patrick Clair and Raoul Marks hold their Emmy Award statuettes at the 2014 Creative Arts Emmy Awards at the Nokia Theatre L.A. Live in Los Angeles.

Getty Images

The last couple of years have been hard on everyone. Everything slowed down and then ramped back up. How has that affected Antibody?

Patrick: The pandemic was obviously very hard. But coming out of 2020 there was a real ramping up and at the start of 2021 there were many shows going into production and there was a run of science fiction shows. I love sci-fi; my dream is to have a whole slate of science fiction shows to be working on. That was the very lucky situation that we found ourselves in. I don’t know if that was happenstance or if people were looking for escape but also – I think science fiction is often very analytical about society and reflecting society’s fears and anxieties so that might have been a reason a lot of them got commissioned.

Book covers for William Gibson's The Peripheral

Patrick: There was a pent up energy by the end of 2020 – people just wanted to make shows. There was one week where we got as many inquiries in a two-week period as we usually get in three-to-six months. The vaccine had just started to roll out, people were confident about schedules – that production could return to some kind of predictability. We’re still working through the projects that came out of the woodwork then.

Aside from The Peripheral, what else has been on your plate, titles-wise?

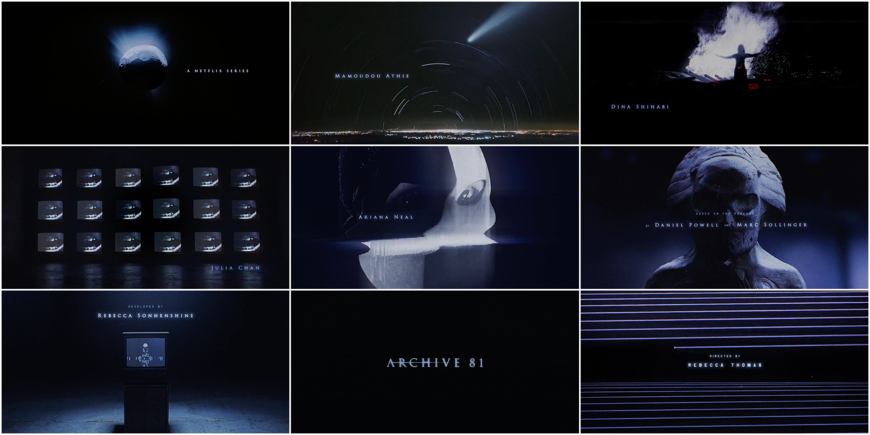

Patrick: We did Interview With the Vampire. We had Westworld Season 4. Wolf Like Me might’ve been last year. I think Archive 81 was last year. We’ve still got a couple of things which haven’t come out yet and aren’t coming out for a little while.

In the age of streaming, a main title needs a reason to exist. You need to be playing some meaningful, valuable role.

Archive 81 (Season 1) main titles

Tell me how The Peripheral project came to you. Were you pitching alongside other companies?

Patrick: We’ve developed a close relationship with Kilter Films over the years, having done Westworld with them. Kilter is a great client, they distinguish themselves by having really great science fiction properties but they’re also the most wonderful and gracious company to work with and that makes all the difference in terms of quality of life in this industry. As far as I was aware there wasn’t a pitch process. The showrunner Scott B. Smith trusted Kilter’s steer and we got to dive in and start figuring out the right way to introduce this world.

What was Scott B. Smith’s direction for you?

Patrick: Scott was very much driving the process. He’s a showrunner that looks at this as a chance to ask, What opportunity do I have here to help tell my story? We don’t just want to be wrapping. If we’re just wrapping then every week people are gonna hit that "Skip Intro" button. You have a lot of main titles that can just be aesthetics and effectively are just branding. They might as well be just a title card. In the age of streaming, a main title needs a reason to exist. You need to be playing some meaningful, valuable role.

Did you put together a bunch of different concepts? Walk me through that.

Patrick: This was an interesting one. It bore a bit of similarity to what we did for The Man in the High Castle, remember that one?

The Man in the High Castle (Season 1) main titles

Patrick: Man in the High Castle has a central symbolism going on – there was a tension between American symbols and Nazi symbols and playing with this alternative history – but it also did some heavy lifting. You saw the map of the new United States, you saw the way it had been cleaved in two by the axis powers, the Japanese and the Germans.

The start of the conversation around this was: we know we can do something pretty for you but what can we do that’s useful? Scott was like, We’ve got a conceptually complicated set up for the show. Anything you can do that can help to – even subconsciously – say that to the audience would be useful.

I’m a big fan of science fiction and time travel shows. I spend a lot of my spare time listening to physics podcasts and I’m interested in quantum mechanic-type things, the multiverse and all of that. At the heart of this series is a clever mechanic that Wiliam Gibson came up with that has a time travel aspect to it, that has a realism to do with branches of the multiverse so that what you do in your timeline can’t influence the future that you’re speaking to, which I think is unique in the science fiction canon. So this idea of trying to see how we could visually connect America from this current era to a far future London became a starting point. And we came up with a line passing through a globe.

Still from The Peripheral title sequence showing the narrow tether across the earth

Patrick: I love the idea of using circles in my work – anything that gets bisected by a graphical line is really interesting to me – but certainly there is this sense of journey in the title sequence which, as you learn the setup to the show, hopefully makes some sense. How do we communicate that there’s this sort of broadcast signal that can transcend future London to contemporary America? There’s this very delicate tether.

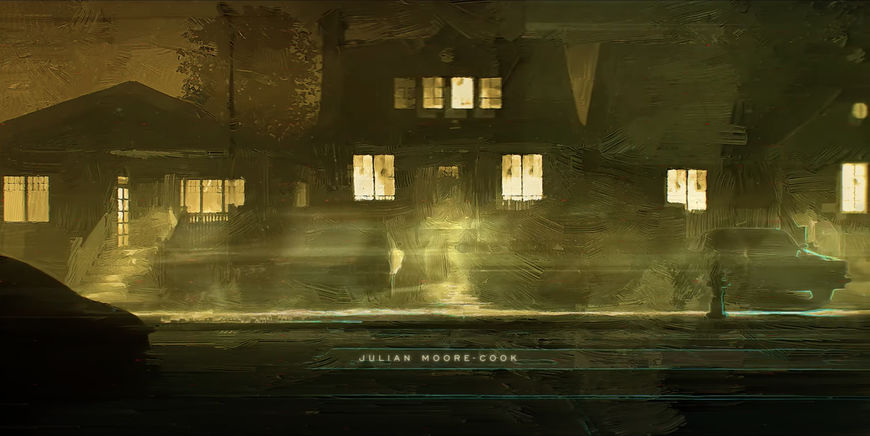

The Peripheral is a really glossy version of cyberpunk that is really mechanistic and futuristic but it’s also got a little bit of Friday Night Lights, a bit of small-town America in it. A warmth.

We wanted to come up with an aesthetic that had all the glitchiness and cool techno of a classic William Gibson story but also had a nod to that small-town, tight-knight community with warm lights and warm taverns, small-town togetherness.

Still from The Peripheral title sequence showing a row of houses

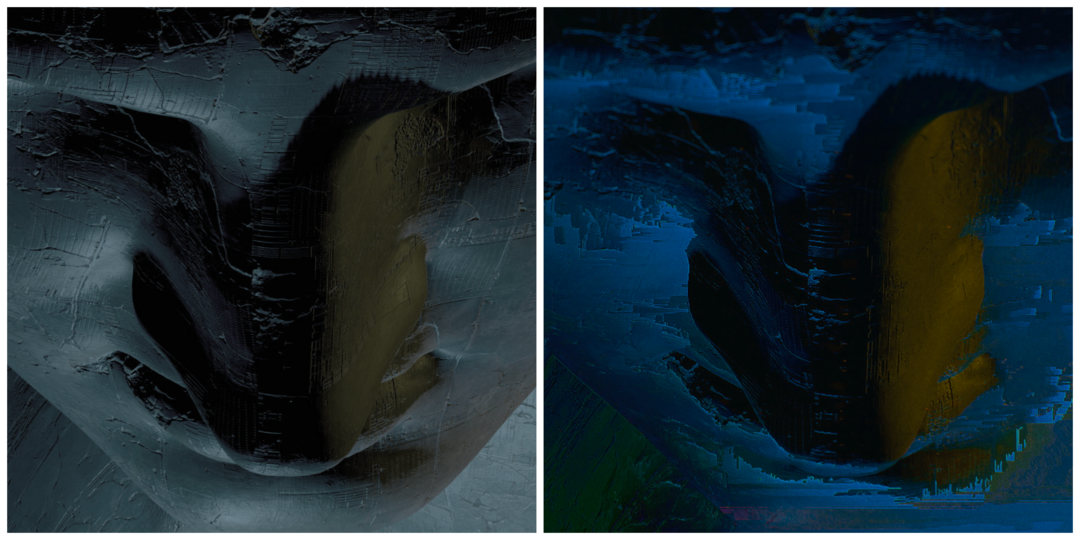

Before and after shots of the house and trailer built in CGI and then with painterly effects applied

Still from The Peripheral title sequence showing a house with a trailer parked nearby

Patrick: That’s where we looked to machine-learning techniques to get this kind of painterly treatment. Raoul’s team would render the CG and then pass it through this machine-learning software that would translate everything into paint strokes, basically.

Before and after shots of future London built in CGI and with painterly effects applied

Raoul Marks: The imagery is created with a mixture of effects but some of the painterly qualities come from a program called Akvis Artwork combined with pixel sorting and layers of distortion. Not quite digital and not quite man-made. A single style frame is “painted” using these techniques and then run through EbSynth to create motion. EbSynth allows the merging of the style of a single artwork with the motion of an “unstylised” animation sequence. The goal here being to have this digitally distorted but human touch to the shots — that would bleed and stretch as each moment evolves. These sequences are then pulled back into After Effects and reworked and layered upon to get an intricate art-directed build-up of subtle textures through each shot.

Patrick: Our hope was that we would come up with something that could speak to both that very human story of a girl living tough in a small town through to this kind of badass future operative that she becomes over the course of the series.

We’re also increasingly using AI scaling software. So if we find a piece of material that we want to use, let’s say it’s too small, we will use AI to scale it up. Gigapixel is one of them. If you get a realistic output from an AI image generator and you put it into a software like Gigapixel it is not able to scale it up in a way that enhances its realism. It’s somehow able to detect – well, not detect but there is something in the image that looks real to the human eye that doesn’t jive with the algorithm. But if you give it something really painterly it’s able to scale up that painterliness really well. You can get a 5K image that has really good brush stroke artefacts.

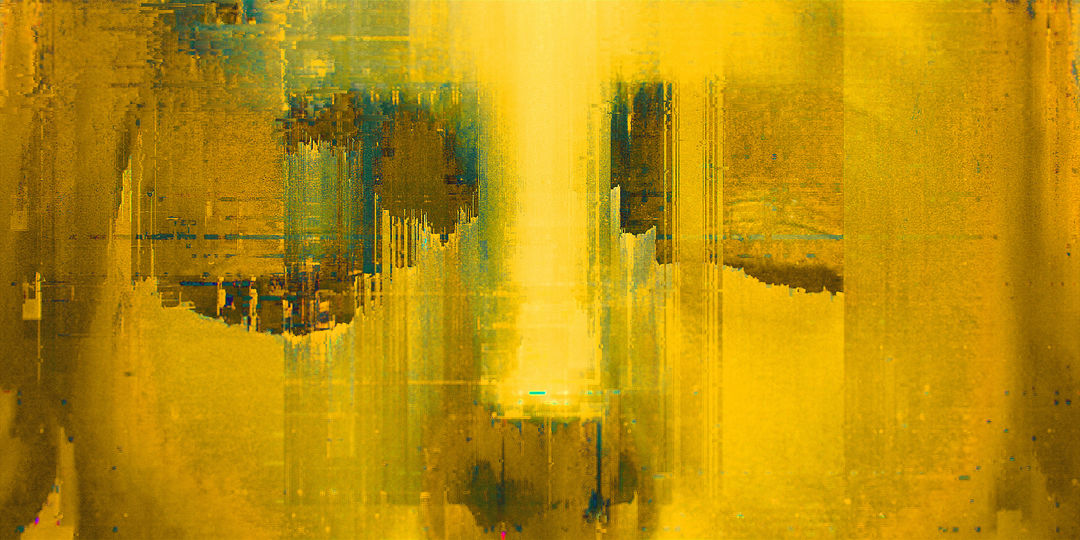

Before and after of Jimmy's Bar built in CGI and then with painterly effects applied

Before and after of an overhead view of a statue face built in CGI and then with painterly effects applied

Did the show provide the base footage? There’s bits of Chloë Grace Moretz and scenes from the show but then there are other materials as well.

Patrick: It’s a total mix. Some of it is aerials from the show. A lot of it is CG. Some of it is projected photographs onto CG. That’s what’s really exciting to me. We didn’t have to have just one way of making images. We could pull images from all different places and in the end they look like they’re all the same aesthetic. The filter is sophisticated enough that it pulls it all together.

Chloë Grace Moretz in The Peripheral

There have been pretty good Photoshop filters for a while that will make something look like it’s been turned into a brush stroke effect, but they haven’t had the capability to be perpetuated in a temporal way. So you would get a different trick every time and it would look like stop motion? Whereas what software’s now able to do is understand that once it’s placed that brush stroke, it should perpetuate that for ten or 20 frames until the form changes, and that’s really been a big step forward.

Wherever you see shots of Chloë, that’s based on photography. I think the eye was cobbled together from some CG assets. Chloë’s got such a distinct look and she’s got such a fantastic screen presence that it’s amazing how much you can distort her and still have her essence shine through, which works really well for the sequence.

Still from The Peripheral title sequence

Still from The Peripheral title sequence showing an eye

You mentioned The Man in the High Castle but the painterly glitch look made me think of your work on Halt and Catch Fire. I feel like this is a new version of that, with the bright gold instead of the bleeding red.

Patrick: Yeah. With Halt and Catch Fire, the designer who was working on the frames would show me a frame and say, doesn't it look nice? I'd say, Yeah, it looks gorgeous, try again. Because the idea was that unless your eyes feel like they’re bleeding, it’s not glitchy enough yet.

Halt and Catch Fire (2014) title sequence designed by Elastic

Patrick: We used some of that same principle here. You get this output from the machine-learning and it looks like a crude impressionistic painting and the challenge then is to disrupt it to the point that it has that fizzing intensity that feels like it’s super-digital as well as having this painterly stroke to it.

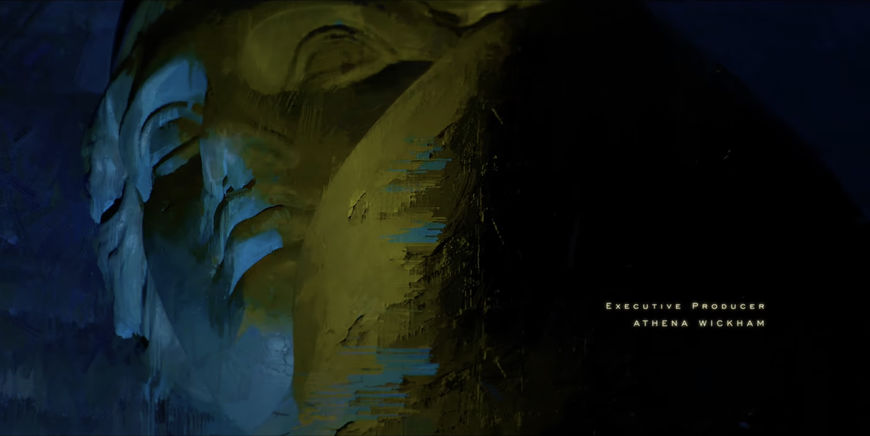

Speaking of painterly, there’s definitely a nod to Renaissance art in the architecture of the new London.

Patrick: This was really a gift from the show’s design. In this future we’ve started – we, the human race – have started to try to repair the environment. So there are these gigantic carbon scrubbers all around London and the world. To make these scrubbers seem less brutalist they’ve covered them in classical sculptures of the Gods.

Still from The Peripheral title sequence showing the "scrubbers" in future London

Still from The Peripheral title sequence showing the face of a "scrubber" structure in future London

Patrick: For this story about people reaching back from the future to try and orchestrate incredibly intricate plans, I was thinking a lot about that idea of – if you want to make god laugh, tell him the plans of man. This idea of the gods watching on was powerful, I thought, in terms of seeing how obviously the plan is going to fall apart as people work through it.

Did you read the William Gibson book, too, to prepare?

Patrick: We read the novel and I re-read Neuromancer and it reminded me of the excitement that I got as an 18-year-old when I first read it – it’s just such a compelling world. The chance to work on a Gibson adaptation is just a dream come true. As usual, getting the deepest possible understanding of how the showrunners view the translation of the novel to the screen is key to trying to make a title sequence that’s going to resonate across the rest of the season.

The Peripheral (Season 1) main title card