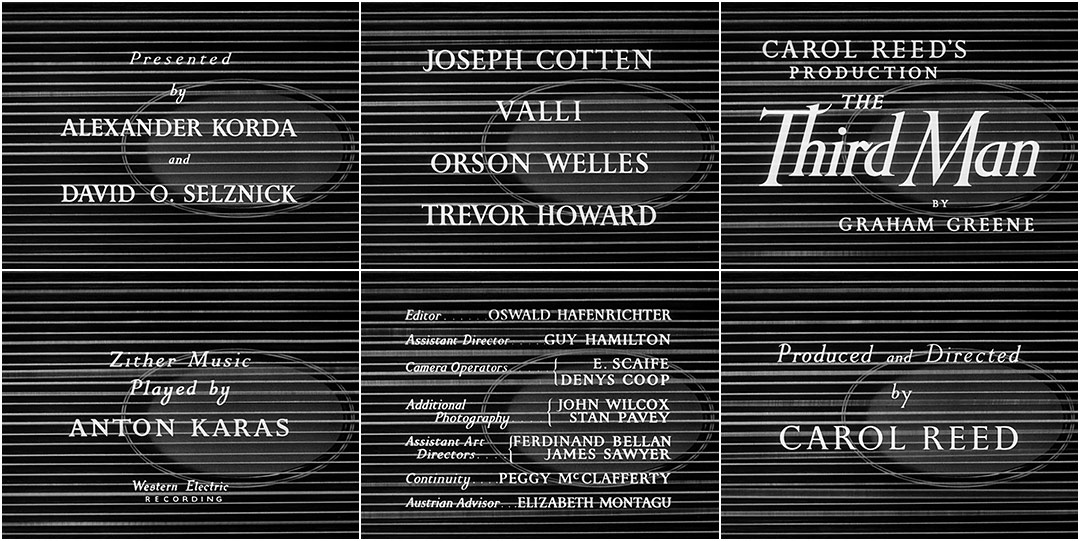

Though the modern title sequence would not emerge until several years later, the main titles for Carol Reed’s 1949 film noir The Third Man remain one of the more distinctive pre-Saul Bass examples to come out of either Hollywood or Britain.

Aligned with the plucked strings and ovoid aperture of a zither – a guitar-like instrument common to Eastern Europe – the simple titles fade in and out listing cast and crew, adhering to the rigid formality of most films of the era. The visuals, though an interesting backdrop for this traditionally mundane cinematic obligation, aren’t what makes The Third Man’s titles noteworthy. Likewise, the star of this sequence isn’t impresario Orson Welles, or even contract man Joseph Cotten. It’s not acclaimed novelist-cum-screenwriter Graham Greene, or the film’s Oscar-winning director, Reed. The star is a humble Viennese musician named Anton Karas.

Discovered by Reed at a cocktail party early in the film’s production, Karas’ involvement proved vital to the film. Indeed, it goes without saying that the sequence, like the movie as a whole, would be nothing without the zitherist's contribution. Given the considerable international talent assembled for the movie (Reed, Greene, Welles, Cotten, and a host of others behind and in front of the camera), that’s saying something. In the same way that post-war Vienna is a character in the film, Karas’ evocative musical accompaniment is as much a part of The Third Man as “hero” Holly Martins or “villain” Harry Lime.

Perhaps no other film until Psycho used the one-two punch of title sequence and musical overture to set the mood and tone of a film quite as effectively as The Third Man did. The sounds of Karas’ zither, with its 34 strings and unorthodox “Viennese tuning,” perfectly embody the ruined Austrian capital’s post-war days. The music captures that mixture of old world romance, naked opportunism, and quiet desperation that characterized the then-divided city. Like Vienna, the tune is immediately alluring and attractive, but despite that initial appeal, it hints that something very untoward, very wrong might be happening just out of sight.

The sequence also acts as the viewer’s first introduction to Welles’ iconic character, racketeer Harry Lime. Lime remains a mystery to both the audience and the characters for much of the film’s 93-minute runtime, but his name is on the tip of everyone’s tongues throughout. In the case of the title sequence, Lime is present by way of the film’s theme song - which bears the character’s name as well as his wily yet melancholy spirit.

In the Criterion Collection audio commentary for the film, director Steven Soderbergh – who riffed on The Third Man with his 2006 post-war thriller The Good German – said that Karas’ unusual and ever-present score lent Reed’s movie a fable-like quality that a full orchestra would have simply spoiled. Similarly, the film’s title sequence is gifted with the musician’s presence, and is elevated beyond contemporary works in the process.