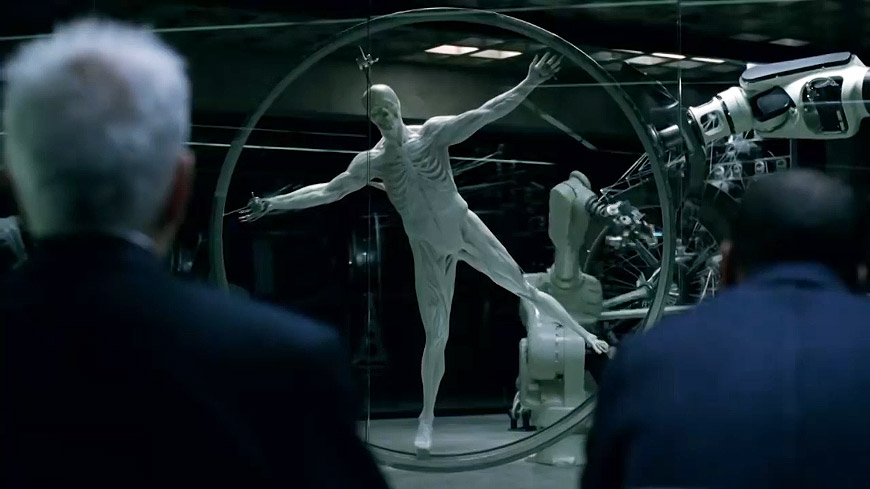

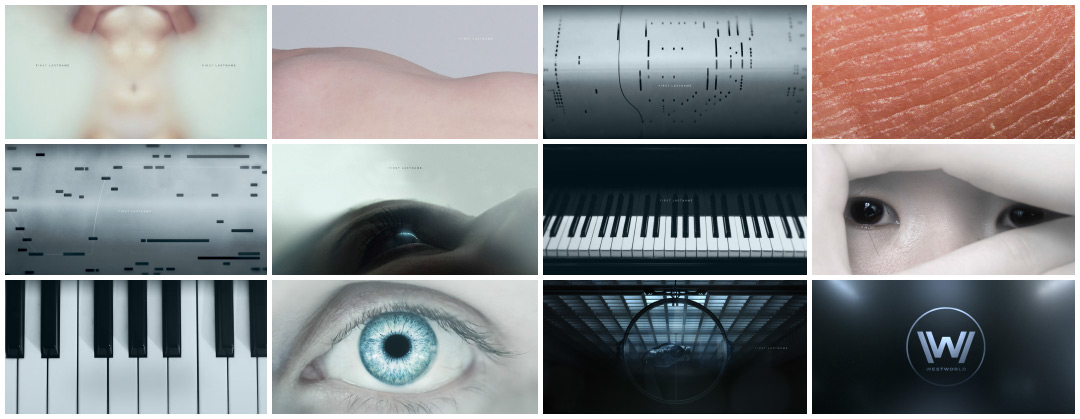

Day breaks over an unfamiliar landscape. That’s not the sun and this is not the natural splendour of the American West. It’s the ribcage of a horse – not bred but built as an amusement park plaything. Robotic tools dance with precision, stringing piano wire and sinew alike, connecting key with hammer, muscle with bone. The horse begins to gallop, Muybridgian in its movement, picking up speed as the machines continue their work. A pale rider takes to the saddle, half-formed and half-cocked, a six-shooter in her grasp. Eyes focus, the piano plays, and two lovers embrace, exposed and unfinished. The piano continues to play, this time without its player – it’s back to the drawing board for this one.

Based on Michael Crichton’s 1973 science fiction thriller of the same name (ultimately the blueprint for Jurassic Park, the writer/filmmaker’s better known “amusement park run amok”), HBO’s high-concept reimagining of Westworld comes courtesy of producers Jonathan Nolan, Lisa Joy, and J.J. Abrams. The trio’s vision is expansive, encompassing both the ersatz Wild West populated by cybernetic cowbots – or “hosts” – and the glossy sci-fi near-future inhabited by the park’s custodians and creators. In the mix are the Westworld’s guests – or “newcomers” as they’re called – who are allowed to live out their wildest and most depraved fantasies in the highly interactive park. Spared no expense.

Elastic’s main titles announce this ambitious vision, evoking the work of Leonardo Da Vinci, Mamoru Oshii, and Chris Cunningham, all while hinting at the broader ethical and existential themes contained within the borders of the story and this twisted tourist attraction. Enjoy your stay in Westworld. Nothing can possibly go wrong...

A discussion with Creative Director PATRICK CLAIR of Elastic.

First off, congratulations on your Emmy win for The Man in the High Castle!

Patrick: Thank you! We feel very honoured. It feels like a lifetime ago that we made it, but it was a pretty satisfying production actually. It was a really good collaboration between us and the production team. If they could all be like that, it’d be great!

It’s been a really big and busy year for Elastic, hasn’t it? You’ve done the titles for Westworld, The Night Manager, Luke Cage, Amanda Knox... How have you and the team adapted to the increase in demand?

Patrick: I think what’s happened is there’s just been kind of a cluster where a bunch of work is coming out all at once. The truth of it is that unfortunately title design can’t take up a lot of our day-to-day life. I try to carve out as much time for it as possible, but ultimately we’re always juggling a lot more commercial projects and that kind of thing. What we are really happy about is that we’ve been lucky to get to do the titles for a bunch of good shows and that’s what we live for. To see them get out there into the world is really exciting!

So, let’s talk Westworld. What has this project meant to you?

Patrick: I think what is really special about the show is that Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy and J.J. Abrams have been extremely ambitious. They’ve built a story that is truly epic – I’m not just using that as a buzzword – it is expansive in terms of its sets, the time period, the aesthetics its combined, and the human themes at the core of the story. It works, it’s emotional, it’s engaging, and that to me is something very special. We felt very lucky to be a part of it.

Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy and J.J. Abrams have been extremely ambitious. They’ve built a story that is truly epic.

Westworld (2016) trailer

Patrick: I’ve really got to commend HBO for making stuff like this. They’re big, risky projects to undertake from a network’s point of view. We get to have jobs we love because places like HBO take those risks. So I really hope the audience rewards them with a fantastic response because that will just encourage more shows of this nature. More great science fiction, more great genre storytelling which digs into the core of what it means to be human and asks really uncomfortable questions. That’s what I really enjoy working on and what I really enjoy watching.

We’ve spoken before about your love of classic science fiction. Were you already familiar with the original Westworld and the work of Michael Crichton?

Patrick: Yeah! It’s something that’s extremely close to my heart. I’ve been really lucky in that it was just at the start of my teenage years when Jurassic Park came out in the cinema. It was a real revelation for me, in terms of storytelling, in terms of themes of technology and science fiction informing a story that was really very human and compelling and exciting and relatable. I’m a huge fan of Steven Spielberg’s films obviously. I think they’ve only gotten more interesting and more complex over time, and I think Jurassic Park is a great example of his filmmaking in a very family-friendly genre.

But seeing Jurassic Park led me to immediately read Jurassic Park the novel, which is really sprawling and detailed and technical. It really lit my imagination on fire at that age. After that I voraciously went and read a stack of Crichton’s books and they very much informed what I wanted to do creatively with my life, they informed the kinds of stories that I found really exciting. It was probably about ten years ago when I started to work in the fields like documentary storytelling – and that was all about technology and ethics and things that had first been raised for me by reading Michael Crichton's work.

Westworld (1973) theatrical trailer

Patrick: It was years later that I finally saw Westworld the film – it’s not totally suitable for ten-year-olds. What really struck me was that I’d been expecting something that was just a story about robot cowboys in a creature-feature kind of way. I expected to be, you know, the cowboys go nuts and it’s all very exciting and violent – which it is – but there’s a much deeper level to it, which was the way that it explored vice and the way vice drives us. How that darker side of humanity is the motivation behind so many of the decisions we make, especially the bad decisions we make. What I found exciting about J.J. and Jonah and Lisa’s take on this was that they really dove into that side of it. The background for me was that I read an interview with Jonah and Lisa on one of the TV rumour sites about how this was going to be their take on Westworld. I thought that was fascinating and thrilling. We’d just done True Detective and were looking around for what would be exciting to do next and the moment I read this I sent an email to Jennifer Sofio Hall [Managing Partner at Elastic] saying: “Jenn, you’ve got to go out and help me hunt this down. I desperately want to work on this show.” And to Jenn’s credit she did exactly that and two years later here we are.

What was the first meeting with the producers about this sequence like? Did they have a vision for the opening?

Patrick: What was really cool about Westworld is that Jonah and the team really took the time to work with us. I think I’ve had more time with them than any other show that I’ve worked on. That was pretty exciting for me because I’m a huge fan of Jonah’s writing and the projects that he’s done with his brother [Christopher Nolan]. His television work really does that same thing where it dives into technology, it uses that changing technology to dive into deep ethical questions about how we live and also just really cool human stories, compelling characters. Getting that time to go back and forth with them was exciting.

Westworld (2016) Creators Lisa Joy and Jonathan Nolan on set.

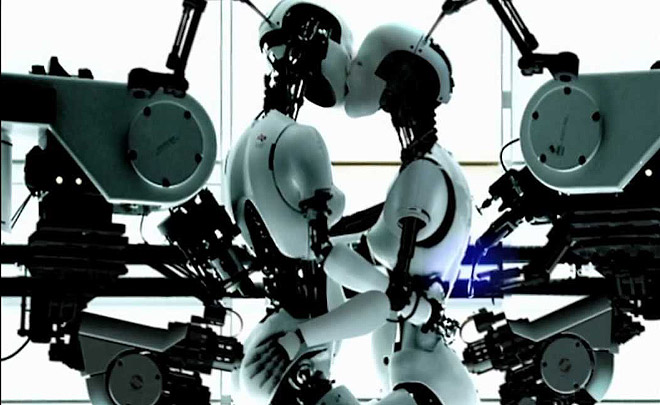

Patrick: It started with a completely blank slate. They shared a lot of material from the show – and this is when there were a lot of different companies in the mix – and we spent a long time, about five weeks, really exploring ideas. We built this massive long deck and I pulled up some of my favourite references. Anyone who’s seen “All is Full of Love” by Chris Cunningham…

I was going to mention that…

Patrick: I was happy to be a bit shameless about it because I worship Chris Cunningham and it seemed like the perfect place to riff on it. I hope no one feels that it’s derivative, but for me it seemed like a chance to exorcise this deep fandom that I’ve had for it. And it seemed like the perfect place to do it because it was dealing with all the right themes and all the right aesthetics.

Music video for "All is Full of Love" by Bjork, directed by Chris Cunningham

Patrick: That being said, there’s so much stuff in the design of the show that echoes the design of The Dark Knight and films like that. That in and of itself harks back to masters like Kubrick. I’m obsessed with circles and squares and symmetry and balance, and how to take real-life situations and transition them into things that become graphic in their simplicity. So all of that was in there.

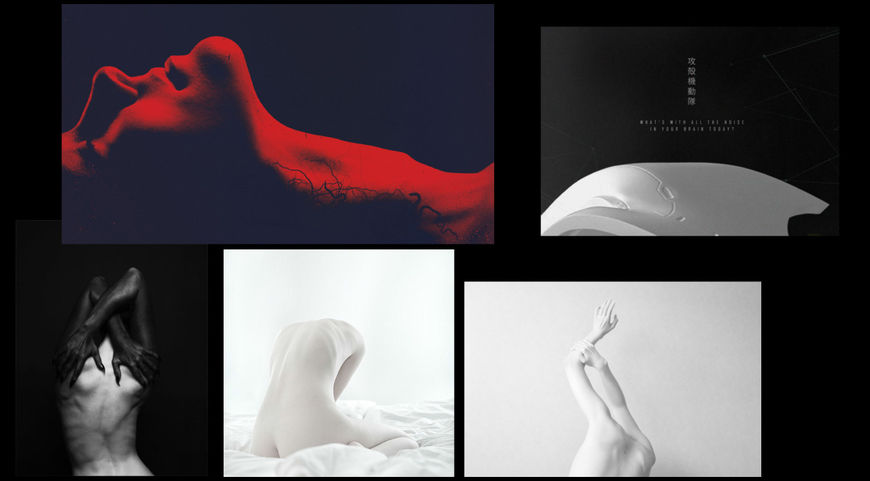

Image set: Westworld (2016) look and feel references

Patrick: We built out this very strong aesthetic for a sequence and we went back and presented that to Jonah and the team. That’s where it got interesting.

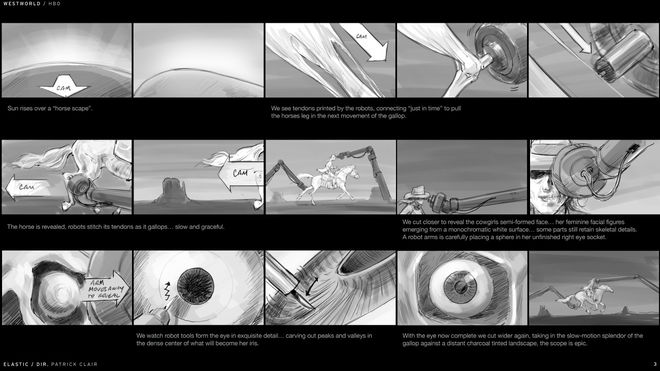

Image Set: Westworld (2016) main title storyboards by Lance Slaton

Patrick: Jonah’s got this brilliant writer’s mind and he dug into it and started throwing out some ideas that were more emotionally challenging than I would have been willing to walk in and pitch. That’s when I felt like we were let off the leash, in a real way but also in a very collaborative way. That’s when we started to dig into the idea of the host who becomes redundant, who is somehow killed at the end. It took us a long time to come to the idea of him going back into the milk bath, but this idea that there was this player that we made redundant was kicked up.

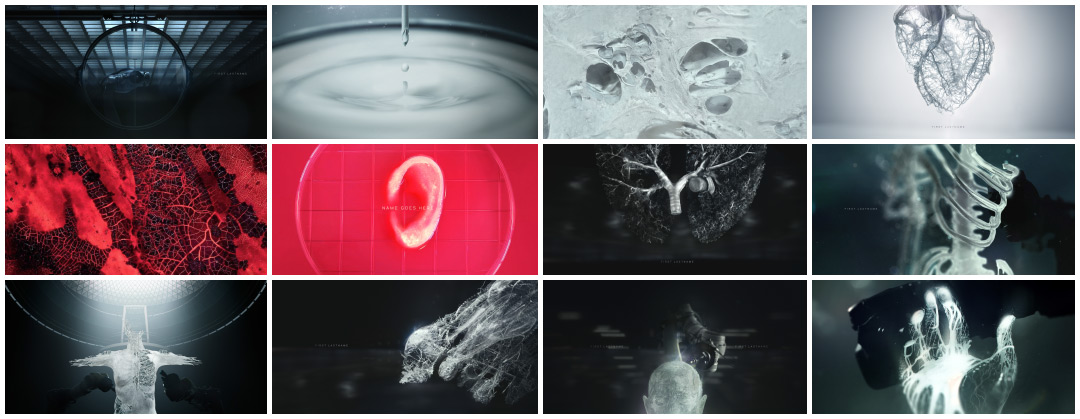

Westworld (2016) styleframes

Patrick: The idea of digging into these robot lovers – robots who were created for the purpose of human pleasure and vice, these kind of dark human things – the idea of them sneaking off for their own romantic, sexual trysts was pretty cool and interesting. Obviously that’s where you get that “All is Full of Love” connection.

Westworld (2016) styleframes

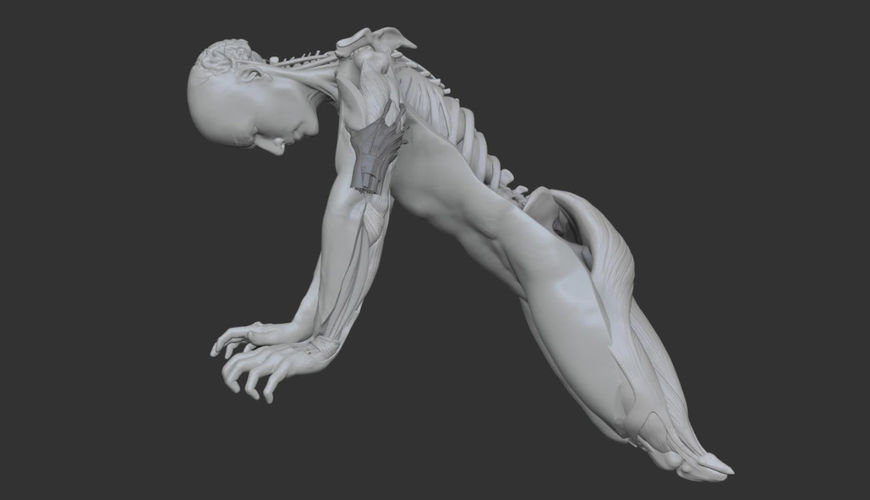

Patrick: Then playing with the iconography of the galloping horse across a Western landscape, but done in such a way that it’s this grotesque skeletal creature being assembled by robots. All of these things started to come up as we sat in this room over near Warner Bros. and thrashed ideas back and forth. It was a process that had enough time to breathe. We started with them in February and we delivered a few days before it went on air [in October]. It was really satisfying and exciting.

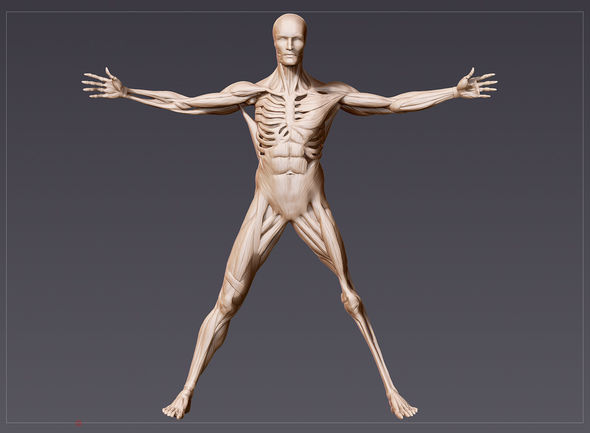

Could you take us through some of the iconography? There are things pulled from science fiction, but also a lot of Western tropes. I’m thinking the eye and the Vitruvian Man in particular. What did those mean to the sequence?

Patrick: My initial thinking before I’d seen any significant material from the show was that we would look at it and find some poetic way to present that back. What was frustrating but a great challenge is that what’s shown in the show is just stunning and beautiful and poetic in itself. So that meant we can’t reinterpret this and make it abstract because it’s so beautiful already. We have to showcase it in a way where it takes on a deeper resonance.

So we studied what was in the show – a great example is the eyes – we looked at some of the early material of them building the full Vitruvian Man and then we went away and designed the way that we thought an eye might form and came back. By that stage the production had created some shots of how the eye might form. I loved what I saw in the show even more and then went away and evolved the idea to incorporate that into what we’d already been doing.

So there was this great feedback loop happening between the design of things within the narrative and the design of things in the title sequence. What we got out of that is that the show does this incredible job of sampling Western iconography, like the cowboys, the cowboy hats, the six-shooters, the horses, and then taking them and putting them in this graphic, sci-fi space. And we tried to take that same approach. What are the most epic, beautiful Western conventions that we can think of and then take what’s at the core of that and put it in a really sort of stark, beautiful, graphic sci-fi frame, and from there try to give it this strangeness that comes from seeing a galloping horse with an exposed ribcage?

You mention the feedback loop. There’s a lot of consistency between what you see in the titles and what’s in the show, which is fairly unusual. In terms of the practical production side, did the show provide 3D assets for any of this stuff or stills of props and sets?

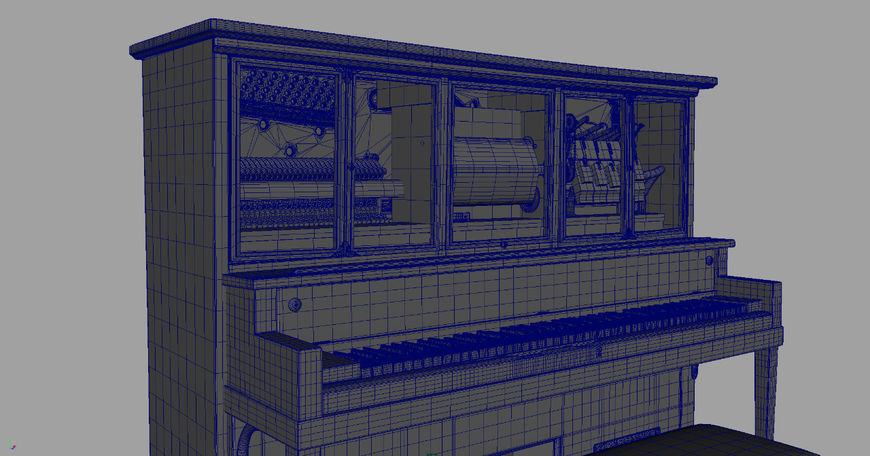

Patrick: They did. With some very notable exceptions a lot of stuff we built from scratch here, but we were very much inspired by material from the show. They had the player piano in their production office and we spent a day taking photos and videos of this thing and how it worked.

Image set: Player piano stills

Patrick: We then tried to recreate it inside the computer, especially because we know that it’s going to be an element that recurs in the show. I’d like to think that we got pretty close.

Player piano 3D model in Maya

Patrick: It really comes down to the fact that Jonah and his team took the time to care about the main titles. That is what leads to good main titles. I look at the ones of ours that I’m most proud of – True Detective, Daredevil, The Man in the High Castle, The Night Manager – they’re all situations where the show’s creators, despite being pulled between edits for eight to ten different episodes, press schedules and all the rest, take the time to get on the phone or get in the room with us and talk and work. I think that kind of collaboration leads to success.

Well, the results speak for themselves. I wanted to talk a little bit about the execution. This is one of your many collaborations with Raoul Marks. Could you tell me a bit about your working relationship with him and what that process is like?

Patrick: Raoul is a close and wonderful collaborator of mine. We started working together back in Australia some years ago and we have a shorthand which I enjoy. We didn’t come from the big cities there, we came from the smaller cities, and both ended up in Sydney about three years ago. We started working together at a time when I’d just won True Detective and we were looking to live up to this brief that we found exciting but equally terrifying.

Sometimes it’s the smallest details that help to tell the story.

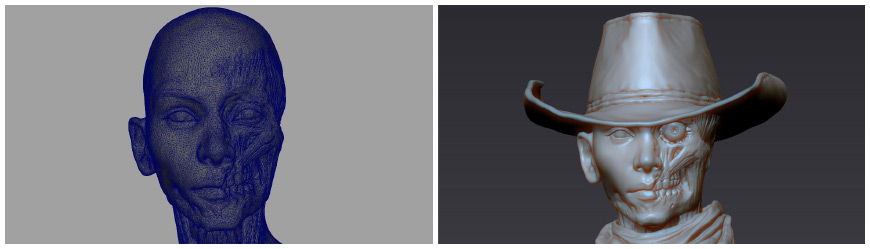

Image set: Cowgirl wireframe and render

Patrick: What Raoul brings to it as a CG artist is that he understands the intent of a shot and the rhythm of storytelling. That’s so exciting to me as a director, to be working with someone who has a deep and practical understanding of the technical side of how to achieve things, but who also understands the emotional impacts that things need to have. Sometimes it’s the smallest details that help to tell the story in a way that can be emotionally powerful, as well as aesthetically valuable.

I wanted to ask you about another collaboration: Composer Ramin Djawadi, who also scored Elastic’s titles for Game of Thrones. Were you able to work with him or his music for Westworld early on in the process?

Patrick: Absolutely. After we’d been working on the development of the sequence for a good while, we were at the point of shot sequencing. Ramin had been working with Jonah on the title theme and we got that. That’s when we really started to lock down how we were telling the story. There’s obviously such a close relationship between the pacing of the music and the story of the titles, the way different elements come into the music, the way different elements come into the titles in quite a literal way – I mean, the piano is there on-screen!

Westworld (2016) Composer Ramin Djawadi

Patrick: So we went back and forth with Ramin a lot. I think his music is breathtaking and I’ve been a fan of his work for so long. It was my first time working with him, so that was really cool. We were never working in the room with him, but we would go back and forth on versions a lot. He was great in terms of us making small changes to the sequence for some technical or practical reason and then the next version of the music would have all of these amazing, artfully executed changes to how the music unfolds to support it in a really interesting way.

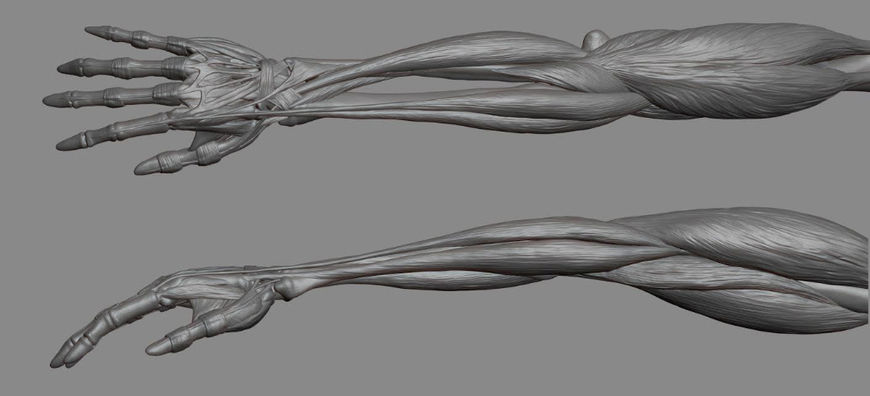

Arm renders in ZBrush

Patrick: What was coolest is that Ramin’s team sent us a bunch of videos of them playing the piano so that we could match all the notes. I got to give a big shout-out to them to say thanks for that, and then also to our team, to Yongsub and Raoul, who then matched that. That was a great collaboration between the composition teams and the animation teams.

So we’re actually seeing basically a skeletal version of Ramin’s hands in the titles?

Patrick: Yeah, totally!

And how big was your team on this production?

Patrick: It was pretty epic. We took a much longer amount of time doing the design development than usual. We spent about five weeks just digging into it. We had a design team that sometimes ballooned up to seven or eight people. Maxx Burman, who was working with us as art director at the time, had a big role shaping some of the early design boards. Paul Kim, who I’m sure we’ve talked about in the past, is a gifted designer. I’m very lucky to have him work on my concepts. He was part of the team and backed up by Jeff Han, who’s fantastic.

Westworld (2016) styleframes

Patrick: Felix Soletic rebuilt whole sets from the show in Cinema 4D just based on trailers we’d found online at the time. I look back at them now and they were some of the key frames that set the tone. I was sitting there with the lighting and animation team late in the process still looking at Felix’s frames for lighting cues. Dan Alexandru and Henry DeLeon were helping on design frames and on research. We had a fantastic modelling team. Dustin Mellum helped us with a lot of the rigid body stuff, but a special shout-out to Jose Limon and Jessica Hurst. Jose, who won the Emmy with us this year and worked on Daredevil and Man in the High Castle with me and now this, he has a gift for shaping the human form that I think is really breathtaking. That modelling phase, all headed up by Kirk Shintani, was pretty key and pretty solid. There’s a bunch more CG artists who I could list but I can’t dig into that now – it was a big team!

Character renders in ZBrush

Patrick: The way that I work best is when me and Raoul can partner on something and really bring that to life. I’d be remiss not to say that Raoul backed up by Yongsub Song, who’s a very gifted C4D, Maya, and After Effects artist who’s been working with us for for the last couple of years, and then Shamus Johnson, who is working with us for the first time and is a young gun who’s figuring out new ways to work in C4D and in Octane, those three guys literally just got into a room and made the thing. They just didn’t really sleep or take a day off for an obscenely long number of days.

You mentioned the long development phase. Were there other concepts that ended up on cutting room floor on this?

Patrick: You’re dead right that we would usually do that, but here we felt that there was such a singular concept with the show that it was really more a case of developing the concept rather than pitching a range of different ones. So we actually had the whole team working on what was effectively one idea. There were different little variations that we explored, but it was one core idea the whole way.

Westworld (2016) styleframes

Which tools and software did you use to put it all together?

Patrick: We did a lot of the modelling in ZBrush, for our organic modelling. We used Maya for a lot of modelling and prep as well. So even though the final product was in Cinema 4D there was plenty of Maya in the pipeline. We comped it all in After Effects and rendering in Octane was a big part of the process. For us, the major step forward was that we assembled some GPU render farms as a way of scaling Octane rendering so that it can work for larger projects. The Octane approach is quite different to traditional renderers when it comes to the hardware and scalability. More and more we find that Octane is a very interesting tool for us to work with. From my perspective, being a non-technical person, it seems to me that Octane is opening up some very exciting areas and it’s going to be a big part of the next phase of production in the industry.

Do you have personal favourite Western or sci-fi title sequences?

Patrick: Alien definitely shines in my mind. They managed to make five letters of Swiss typography become beautiful but more importantly something deeply ominous and really exciting to watch. I like that kind of simplicity. That’s always the battle for me: how do we get back to something simple?

If you can’t describe your idea in a sentence then you don’t know what it is.

Alien (1979) title sequence designed by R/Greenberg Associates

Patrick: One of my executive producers once said to me: “If you can’t describe your idea in a sentence then you don’t know what it is. If you can’t describe your story in a sentence you don’t know what story you’re telling.” That just echoes in my head every time I sit down to start a job. There’s invariably two or three moments of crisis where either the client or you are saying, “This isn’t working” or “This is not what I want it to be.” What we’re always hunting for is how do we bring it back to the core, how do we make it something simple?